Nicolas M Iglesias

Interview with Nicolas Iglesias

Nicolas Iglesias

By: Ashley Alderman and Emily Shlapak

Introduction

My partner and I interviewed Nicolas on Monday, November 26th, at his office in his place of work, Rocktown Realty. Nico was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1974 and lived there until he immigrated to the United States in 2000 at the age of 26. He currently resides in Harrisonburg, Virginia after moving from Miami in 2015. He works full time as a realtor at Rocktown Realty. We interviewed Nico to find out information specifically about his life in Argentina, what lead him to becoming a citizen of the United States, and ultimately about his life here in Harrisonburg.

Life in Argentina

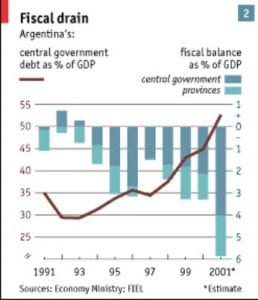

Nicholas Iglesias is 44-years-old and was born and raised in Argentina. At home in Argentina, him and his father owned a printing company, but the business was not doing well enough to support their family. The lack of success from their printing company is what ultimately pushed Nico to start a life in the states so that he could make a better living. In 2000, he was 26-years-old when he left Argentina to find work in the U.S. What’s important to note is that at the time of Nico’s departure, Argentina was undergoing a severe economic crisis, which was affecting their small printing business. During most of the 90’s, Argentina led mostly all Latin American countries in terms of economic growth. Everything took a turn in the late 90’s due to the country’s currency peg to the U.S. dollar, various fiscal policies, and an excessive amount of foreign borrowing. This left the country in a major currency, debt, and banking depression (The Argentine Crisis 2001/2002).

As seen in the graph, it’s clear to see that Nico left Argentina right before the country was in complete economic disarray. The graph shows the severe dip in the government’s debt as a percentage of GDP. In December 2001, President Rodriguez Saá announced a default on Argentina’s sovereign debt, in which he was forced to resign a few days later. Four different Presidents attempted to take control of Argentina’s economy in December 2001, none of them managed to stay in office (The Argentine Crisis 2001/2002). The volatile economic state of the country coupled with political instability was the “push” from Argentina that justified Nico’s decision.

When asked about any significant event that helped Nico transition to American life, he provided a fascinating response that encapsulates the essence of his “push” from Argentina and his “pull” to America. He said it wasn’t really an event, but the “option to have a future is the big difference.” Nico said that in mostly all of South America you could have an “okay” business but then “in two months, something changes, new taxes… or deflation… You’re gone. You have no idea what’s going to happen. It’s completely unstable.” This brilliant and eye-opening response shed light on the fact a lot of countries current economic/political state does not allow for its own people to have the option of a foreseeable future. Due to Argentina’s state when Nico left, he felt that the country was too unstable to be able to organize himself and plan ahead. That is a luxury that Americans take for granted the ability to make 5 or 10-year plans for the future with the reliance that the government or economy won’t radically decline/shift in an abrupt way. We see our stability as a necessity rather than a luxury. Nico’s response to this question perfectly illustrated his motivation to leave Argentina and migrate to the states.

Change to America

When Nico first arrived in the U.S. he settled in Miami, Florida. A friend he had attended elementary school with was already living in Miami; therefore he saw it as the best option for a place to start. Connecting with this friend allowed him to become part of an already present surrounding Latino community which helped make the move and acclimation to the U.S. easier. He entered the U.S. with a B2 visa, or in other words a tourist visa (Temporary Work Visas). His tourist visa allowed him to stay for 6 months at a time and but did not allow for employment. In Nico’s first year he traveled back and forth from Miami to Argentina 17 times. When asked what he did to make money he explained, “what I was doing is coming in, buying some stuff, buying electronics, buying clothing, going back, selling and trying to start a kind of a business and make a living off that.” He also worked multiple other jobs to make ends meet, one included making pizza. When traveling back to Argentina he would often get asked about his work, receiving comments such as “Why are you doing it in Miami and not doing it back in Argentina?” when relating to pizza making or he would get ridiculed, his friends constantly asking “why he was going to go and wash dishes for the gringos over there?” and yet these comments didn’t affect his plan. His response would be “Because if I’m doing the dishes, I can live with that money.” His jobs and the opportunities available in Miami were allowing him to save and count on money that wouldn’t have been possible back in Argentina. His employment held in Miami, and the money coming from it showed him a future that he could count on, without the threat that was present in Argentina, that one day he would wake up to it all changing or disappearing.

He received an opportunity to obtain a temporary work visa through his friend who was already working for a cellular company. His friend was able to connect Nico with a job and chance to put down permanent ties in the U.S. While this job created more stability for Nico, he still worked hard, once even holding three jobs at a time. He continued to work for the cellular company for 6 or 7 years until they went under bankruptcy. Due to this he then transferred to another company which also offered him a work visa until he eventually started up his own business. He was able to apply for his green card after 6 years and then worked on applying for his citizenship through his new LLC.

Around the time Nico was applying for his green car, he married his now wife Sandra, in Miami. Sandra was from Columbia and had already been going through her citizenship process when they met. She was steps ahead of Nico and once she was finally a citizen, he was able to expedite his process through her file as well. He and his wife lived in Florida for a total of 5 years after they got married. His business, Pro Arco LLC, a cargo company which specialized in international business, had flourished, however it held a lot of responsibility which was often put solely on Nico. After receiving an offer to sell in 2015, Nico, Sandra and their dog, Shanty decided to complete their mutual goal of moving north. During an annual road trip the trio happened to stop in Harrisonburg where they found everything they were looking for.

Work in Harrisonburg

In September 2015, the family of three packed up and moved to Harrisonburg. When asked why they choose Harrisonburg, Nico responded with one word, “adventure.” Due to the fact that Nico wanted to cut back on working and the original headquarters of Rosetta Stone, the company his wife worked for, was located in Harrisonburg, they saw this as the perfect choice for them. Once settled here Nico planned to take a yearlong sabbatical, however, this ended after just a short 3 months. Previously in Miami, his clients use to ask for and trusted his advice given on investments and properties. With this move, he decided that was what he wanted to continue, but in a more official manor. He got his realtors license in hopes of making a profit on the side of his everyday work, however it ended up becoming a bigger focus than he expected.

“I’m probably not the real, the ideal realtor or, the one that you will figure out that is a realtor,” Nico claimed. Starting out his work mainly focused on investing in properties, calling up those who had asked for advice previously and offering his services officially. His previous work in international business allowed him to create contacts and clients who don’t even live in Harrisonburg, but who now own the buildings. Often times he has sold properties without the client even seeing them. He sees his work as mainly numbers and can convince a client or potential client with only 10 minutes of talking about the logistics of an investment. While he started with a more adviser/behind the scenes approach, his growing connections to Harrisonburg as well as the Latino community are resulting in him becoming a bit more hands on.

Life in Harrisonburg

Nico’s first impression of Harrisonburg is that the place truly encompassed its name of being the “Friendly City.” During Mr. and Mrs. Iglesias’ first Thanksgiving in Harrisonburg, they were completely by themselves and they did not even know where they could buy a turkey. They went to Food Lion and someone that was stocking the shelves took 10 minutes out of their time to explain to them where they could go to buy one and how to get there. Nico recounted that you would never see that type of hospitality in Miami, they’d probably just tell you to “go to the store.” Him and his wife’s encounter with the Food Lion employee was their first symbolic interaction that shaped the way they viewed the city of Harrisonburg. He feels as if he’s acclimated very well to Harrisonburg, especially because it is not a large city. Nico remarks, “I mean I, I know people all around and being here only three years. So that’s the main, the main thing you have friends all over and that helps, really.”

Something important to talk about is the influx of immigration that has occurred in the Harrisonburg community the past few decades. In Harrisonburg and Rockingham County (2017), 16.7% of its citizens are foreign-born, which is bold compared to 10% in the state of Virginia (A Brief History of Immigration in Harrisonburg). More notably there has been a “Latinization of the Central Shenandoah Valley.” Although there are many factors that influenced the surge of immigration in the 90’s, one of them was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that was signed in 1992 and took effect in 1994. NAFTA had a negative impact on small Mexican farmers, which caused an influx of Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. Refugees and immigrants were also drawn to the Shenandoah Valley due to the poultry industry, which mixed the pot of ethnicities that were present in the community (A Brief History of Immigration in Harrisonburg). Essentially, “immigrant recruitment” was occurring in the valley due to the need for workers, notably on farms. The city of Harrisonburg was starting to adapt to the strong presence of immigrants at different levels of the community. According to New Bridges, the Immigrant Resource Center, “by the late 1990s, Harrisonburg City Public Schools provided translation and interpretation support for multiple languages, including Spanish, Arabic, Kurdish, and some Russian” (A Brief History of Immigration in Harrisonburg).

Nico is satisfied with the Latino presence in Harrisonburg because it keeps him socially engaged with the community. Nico says, “We are always getting together for, I would say probably once a month just for fun. Having dinner in different places. We have a group of, I would say probably seven to eight couples, kids, dogs and just get together, have dinner, or probably go to a salsa night in the cross keys vineyard.”

Nico’s Latino friend group is part of his contexts of reception in Harrisonburg because it has helped him adjust the most to life in Harrisonburg. Going from Miami to Harrisonburg certainly entails a form of culture shock, but we think that his Latino connections within the city is what keeps Nico grounded. Nico’s wife was born in Colombia, so this is also a feature of Harrisonburg that she benefits from. As pictured, Cross Keys hosts Salsa Night on a monthly basis, which is a primal example of the city accommodating to the ethnic community. Cross Keys hosting these types of events that appeal to Latinos is another context of reception for Nico, in other words, another way that makes him feel more connected to the community. These types of international events are crucial to a growing, cosmopolitan community that seeks to make its newcomers feel as at home as possible.

Attitudes

When asked if there has ever been bias placed upon him due to being an immigrant in his line of work Nico had a few answers. “Yes and no. I mean, the environment that we have in this company, it’s completely different as you can imagine than any other company that’s, that needs to be said. It’s a complete difference. One of the owners was born in, uh, Netherlands, uh, and lived all over the world, so he speaks like six different languages. We have people from at least 10 different countries working in the company.” Rocktown Realty therefore being a diverse and accepting workplace like a lot Harrisonburg, however he has experienced some issues with his clients. “I get phone calls from a lot of people that I don’t know and as soon as they call me on the phone and get my accent or my last name it’s, “uh, I already have a realtor” or “I’ll call you back later”.” Nico also noted the difference in perceptions in Harrisonburg compared to Miami, “Usually in Florida if they are not really, let’s say, pro-immigrant. They just left you alone. That’s it. Over here, they let you know that they are not willing to let you be basically.”

Nico’s remarks highlight that while Harrisonburg may be called the “Friendly City” and that it has become a lot more diverse over the last few years, there are still people that aren’t as accepting. The context of reception in this case would be that the people and communities in Miami were a lot more willing and/or accepting towards immigrants than in Harrisonburg. We believe this is due to the vast population of diverse people, including immigrants, which are integrated into Miami’s society. If there are any issues, they often aren’t showcased, merely they let it be. While there may be some people against the immigrants in their society, they don’t go out of the way to make people feel rejected or unwanted, they’re merely indifferent. Whereas in Harrisonburg, the “natives” as Nico comments, sometimes aren’t afraid to blatantly show their bias, recalling that “When we moved here, I mean the city was extremely friendly. We know that at the very beginning. But every now and then we, when you hear someone that is really against you– is really against you.”

Conclusion

Nico has been living in the U.S. for 18 years now. He has built a home, strong connections to his community, as well as a successful career and continues to do so.Curious to see his opinion on his journey as an immigrant, we broached the question about if he had any advice to give to others thinking about immigrating to another country, “looking back, I will always try to get a helping hand in advance. Try to know where I’m going to land and if there’s going to be uh plan B, let’s say.” When we asked Nico to look back at his entire experience immigrating to America, in retrospect, he told us something very humbling: “No, I wouldn’t change anything. I mean, again, that’s basically my way of life. I mean, I did it at the moment, I took my time, I thought about it, I thought this was the best, and if it wasn’t, okay, next.” Venturing into the unknown, not knowing anything besides the fact that the journey will be arduous is a daunting pursuit. What really struck us about Nico was his humility. He was brave enough to take a risk, brave enough to make mistakes, and most importantly, brave enough to learn from those mistakes. He did not judge himself when he messed up, he said “ok, next,” and forged forward. No thinking, just doing. He said he was going to America, and that is exactly what he did. For foreigners to come to America, that long process alone is emotionally and physically taxing. The idea that they can then start a life here and lead a life they are proud of is genuinely impressive beyond words. The resilience of Nico, among thousands of other immigrants, is an admirable quality that we truly need to have more of in America.

Interview with Nicolas Iglesias

By Ashley Alderman and Emily Shlapak

November 26th, 2018 at 4pm

Emily Shlapak (1) : Alright, so if you wanna just start with your name, where you’re from and what life was like, I guess in Argentina,

Nicolas Iglesias(2): What life was like in Argentia ha, well my name is Nicholas Iglesias. I’m from Argentina, i am 44 years old and I started coming to the states when in 2000. Uh, there was a big economic crisis at that time between 2001 in Argentina. I was working with my dad in a project and we own a printing company lets say, and it was not giving us enough money to the both families. Yeah. So I just decided to let him start to stay over there and I’m moved here and start from scratch. But it was easier for me being 20 years old.

Ashley Alderman (3): So you were 20 when you came?

Speaker 2: I was 26

Speaker 1: What was the process like to um, get your visa?

Speaker 2: Extremely hard and difficult. It was, I mean when I first came I came with, uh, what was it, a tourist visa, so it all only allows me to stay for six months, not work for anybody. So what I did was for the first year I traveled back and forth 17 times actually.

Speaker 1: In six months?

Speaker 1: No in a year, a year. Crazy. Let’s say about once a month, let’s say 17 months probably. So what I was doing is coming in, buying some stuff, buying electronics, buying clothing, going back selling and trying to start a kind of a business and make a living for that, uh, after that, I mean, long story short, I started working for a company that sells cellular phones and they offered me to get my visa.I got the visa from them, a work visa, a working visa from them. And that every time that since I started trying to do my own business, what I did was I create my own company and start building my own LLC to get my visa through my company.

Speaker 3: What was your company? Like cellular?

Speaker 2: Uh, yes. It was a generic, buying and selling whatever I can do a basically for export to South America, especially different Argentina. And uh, that was the beginning of it. I worked for three different companies at the moment. The first one was going towards bankruptcy, so I moved to another one, got my visa, transferred the visa, and then after six years I was able to apply for my green card. At that very moment I got married to my actual wife. She was already a citizen, or getting her citizenship probably a year after we get married.

Speaker 1: Was she from Argentina as well?

Speaker 2: No she’s from Colombia.

Speaker 3: She’s went through the same process kind of too?

Speaker 2: Kind of yeah, she did the basically the same process. We didn’t meet at that time, but she, she could make it faster than me,. So when I could apply for my green card, she was already applied for her citizenship. So I did my green card on her file, let’s say. It was faster for me.

Speaker 1: When you first came here, where did you come to? Harrisonburg?

Speaker 2: No, no that was in Miami. I lived in Miami, uh, 15 years.

Speaker 3 : What made you go to Miami first?

Speaker 2: It was easier. It was the idea to live with some Latino, like community. So Latino community is surrounding, make it easier. One of my biggest friends was living there. Uh, so I moved here, moved there and started working with him.

Speaker 3: So it was people you had previously known?

Speaker 2: Yes. I mean only one, one or two friends that we actually did elementary school together. So I decided to start there. And my always, my goal was to move somewhere, let’s say northern to live really in the states basically.

Speaker 1: Uh, did you guys work together?

Speaker 2: Yes, my friend?

Speaker 1: Yes.

Speaker 2: Yes, I worked for him. He was working for um, a, a cell phone company and he brought me into the company and we worked together for probably six or seven years. Then when the company was heading to bankruptcy I just moved onto another company.

Speaker 1: Did you like living in Miami?

Speaker 2: Yes and no. I mean it’s a big city, a lot of options, but everything is a, I don’t want to say a mess, but kind of. The worst thing was basically the, the weather weather was too much. Way too much, I mean eighties, at least all year, round around way too much. So again, after we got married, uh, probably five years after we were married, yes, between four or five years, we both have the same idea of let’s move somewhere else and it just happened to be in Harrisonburg

Speaker 3: You came over alone you said?

Speaker 2: Yes

Speaker 3: But did any of your family ever come over?

Speaker 2: Not to live here. They visit at least once a year. Uh, I’m actually going to Argentina next week for 10 days. Uh, it’s my oldest brother, my only brother, 50th birthday, so I’m flying to. I’m going to see him and stay with my family. My mother was here about two, three weeks ago. She usually comes once a year, at least, my brother every now and then. I haven’t even seen my sister in three years, uh nephew’s every now and then. It’s, I mean it’s long trip and an expensive trip, so it’s not easy for them to come over, especially big families.

Speaker 1: How did you make the decision to come to Harrisonburg, like harrisonburg specifically?

Speaker 2: That’s uh, Okay. I will, I mean, if I have to say only one word, it will be adventure basically. Uh, I worked for myself for the last 15 years probably, or at least 10. I owned a cargo company in Miami. I was working way too much to be honest. All the records, all the stuff was on my shoulders, all the time. Um, so once a year , for usually holidays we did a road trip. Sandra, my wife, the dog and me, just the three of us driving around somewhere, usually north specially to Canada. I have a friend who was in elementary school with me yet, so I’m still in touch with him and try to meet each other at least once a year with him. So on one of those trips we happened to stop in harrisonburg. Uh, we liked the city, it was nice, it was friendly, completely different. We were like okay this has all the seasons, you can actually see the changes.

Speaker 1: Yeah that’s why my family moved, cause I use to like in Florida, like West Palm beach area.

Speaker 2: Okay, well the last, my last address in Miami, Florida was um Davy, fort lauderdale?

Speaker 1: Oh okay fort lauderdale! Yeah but I was from Jersey, but we missed the four seasons so we moved back so that’s why. Yeah.

Speaker 2: So, and that trip also I mean, uh, Sandra, my wife works for Rosetta stone, Rosetta stone start here, it started here, the very best big, first beginning of the song encouraged.So, and that also, I mean, uh, Sandra, my wife works for Rosetta stone, Rosetta stone start here, it started here, the very first beginning of Rosetta stone was in Harrisonburg.

Speaker 1: Oh I was not aware of that

Speaker 2: So she is, a Spanish coach, online coach, so they have to work from certain cities. Usually it’s main cities, Miami, New York, Texas, whatever. And this is one of them being the first one that they had. And we said okay, we can, she can still work from home. And I just, uh, we just decided to move here, one year after we were basically moving.

Speaker 1: What made you transition from the cargo business to realty?

Speaker 2: Uh, I again, was in international business for many years. Most of my clients have too much money in their own countries. They can’t spend it over there because tax purposes or that kind of problems. So they started looking at me for some advisors. So I’m trying to see where they can buy or what they can do with the money. I help them to buy many properties in Miami, but without a license, just telling them what to do or where to buy. When I sold the cargo company, I moved here with an idea of one year of a sabbatical year and do nothing and just wind down. And after two or three months I’d say, okay, I can get my license. I got my license and start exploring a little bit more and started looking at properties. I bought one for myself as an investment. It was too good to be true too. So I get really deep into it. Got into it, got my license and thought okay, I can do something on the side to make a profit and you end up with it being way deeper and bigger than I thought. So I just focused completely on it.

Speaker 1: Do you enjoy being a realtor?

Speaker 2: Yes. Yes. Uh, I’m probably not the real, the ideal realtor or, the one that you will figure it out that is a realtor,

Speaker 3: Like the image?

Speaker 2: The image. Yes. The standard, because for example, I tend or try not to work on the weekends, which is not really a feasible for our standard realtor, but um, most of my clients are investors. 90 percent I’ve focused in investing in properties and I have probably , I can say about 50 properties I have sold, that the buyer didn’t see because it’s just numbers. I mean this is a property, I can do this, I need to do this, do this, and then it is going to be rented at that, okay done, make the offer. So it’s kind of a different approach. But I’m getting lately, probably for the last six months and in the near future, I’m getting involved really deep with the Latino community so that will make me probably have to move a little more on the weekends. But the last, we just added two new realtors to the team and both speak Spanish and they’re both new so probably all the leads that need more attention and more being taken care of over the weekends, they will help me and do that.

Speaker 3: Has being an immigrant and your previous knowledge of the international trades and all that, has that helped you as a realtor or just ever affected you negatively?

Speaker 2: No, it helped me really. I mean, again, most of my clients, at least my first clients were who I started calling and I saying I can do this instead of a meeting. There’s a big difference buying a condo in Miami for $200,000 and one here for 50.

Speaker 1: Yeah, it’s crazy.

Speaker 2: So calling them with that kind of differences and the rent here, it was even bigger than the one that you can have in the $200,000 in Miami. They were starting calling me back so it really helped me, the knowledge, and I’m a number person. I am. I mean it just comes to me. It’s, it’s easy for me. So all that as a background really helped me. It probably hurts me in the kind of way that I’m really a, again, linked to investments and that kind of unattached to a property. I mean if it will make me profit, I will give it. If no one will sell it I’ll make you sell it. So every time that, I mean, everybody’s attached to a property or thing that the property is worth more because they grow up there or something that is kind of hard for me because I’m, I see numbers, but uh, other than that, it really helped me

Speaker 1: Have you experienced any bias in the workplace or from potential clients due to being an immigrant, so like people’s attitudes towards you or

Speaker 2: Hm? Yes and no. I mean, the environment that we have in this company, it’s completely different as you can imagine in any other company that’s, that needs to be said. It’s a complete difference. One of the owners was born in, uh, Netherlands, uh, and lived all over the world, so he speaks like six different languages. We have people from at least 10 different countries working in the company. So that’s a different, completely different kind of environment. With customers- yes, I have been, I mean, every now and then we do a lot of investment in advertisement in Zillow. So I get phone calls from a lot of people that I don’t know and as soon as they call me on the phone and get my accent or my last name it’s, “uh, I already have a realtor” or “I’ll call you back later”. Yes. But either investors and they hear me ten minutes about numbers then I can flip them over, but uh, I need to fight it. I need to fight it yes.

Speaker 1: Would you say it’s more so or less than in Miami?

Speaker 2: I’m not in same field that I was in Miami, but I will say probably, you can feel it more here probably, because I’m dealing with a lot of, uh, investors from, I mean from, and I want to, I don’t want to say native, but really American people looking for investors for the investments that it’s a completely different scenario than Miami.

Speaker 1: Miami would probably bring people from all over too.

Speaker 2: Yeah. So they, I mean the, they’re used to it.

Speaker 3: Was it more worse say like when you first got here? Because Harrisburg has grown to be more of a diverse/friendly place.

Speaker 2: Yes, yes, yes, yes. When we moved here, I mean, especially now after three years we have a big group of Latino friends, but uh, when we moved here, I mean the city was extremely friendly. We know that at the very beginning. But every now and then we, when you hear someone that is really against you– is really against you.

Speaker 3: Yeah, there’s no medium. They’re stuck with their older values.

Speaker 2: Usually in Florida if they are not really, let’s say, pro-immigrant. They just left you alone. That’s it. Over here, they let you know that they are not willing to let you be basically.

Speaker 1: Um, was there any like significant event that happened either here or in Florida that helped you transition most to American life? We got the big questions here.

Speaker 2: *sigh* I know ha. Uh, it’s not one. Uh, basically the option to have a future here is the big difference. That, uh, every time that I’ll go back to Argentina and speak with my friends or my family and say I can predict, I can know what I’m going to be doing in the next five years, at least, 10 years. That’s a big difference. Back in South America let’s say, I mean even, I mean Columbia, Argentina, whatever, we can be, you have no idea how much, the value of your money today or tomorrow, or at two months.You know inflation, deflation,

Speaker 1: So it’s hard to like plan ahead?

Speaker 2: Correct. Yes. Because I could have an okay business in Argentina or Colombia, so any, any country in South America, let’s say, as it is today, Chile out of the question basically it’s more stable. But all the rest of South America, you can have a okay business today in two months, something changes, new taxes or money drops or deflation, whatever. You’re gone. You have no idea what’s going to happen. It is completely unstable. So that was a big difference and that was what made me come to America and say I can start, work hard, but make some progress and say okay, in 10 years I want to do this and being able to.

Speaker 1: So it helped you transition because you could organize yourself and plan ahead?

Speaker 2: Mhm, yes, basically.

Speaker 3: Were you originally planning on staying in the U.S.?

Speaker 2: Yes. That was the plan. I have no idea why. I mean, it was, uh, when I came to the states for the first time when I was 14, when my, when my dad was working for Dupont and one of his trips he just brought me in. Okay. I wanted to live there and it was just on the back of my mind all the time. And again, in 2001 when I started flying back and forth, there was also the option to go to Canada. It was probably easier for me to get the visa, whether a student visa or do something different, but I just happened to be Miami. I mean, just I choose.

Speaker 1: From people back in Argentina, what do you think holds them back from coming here and starting a life?

Speaker 2: Uh, it is probably English will be one of, the language barrier could be one of the options. Uh, I studied English in my, in Argentina for 12 years. It’s not that common, but most of the middle class will at least have a knowledge and be able to communicate. But, I mean the idea of a friendship in the states is completely different than the one that we have in Argentina. And even, I guess, that Argentina is completely different to the rest of South America. Front door of my house was not technically open for security purpose, but any friend that was just walking over and just knock on the door. Come on in. Let’s get a coffee, drink mate, or whatever altogether every time. No, no need to call ahead and make an appointment or other kind of stuff that basically we are used to here. I mean it’s really weird that or really not common for you to go over a friend’s house and just knock on the door here.

Speaker 1: That’s true… you got to call..

Speaker 2: Call ahead, oh you’re going to be home two hours. I’ll be there. So over there is just, I’m here, let’s do something. So I guess that’s one of the bigger issu es and family, being able to have a family, being content with family, that’s probably one of them.

Speaker 3: Do you have any children?

Speaker 2: No.

Speaker 3: Do you plan on having any?

Speaker 2: We tried, we planned, but it didn’t work. We are not going to be crazy about it. We have a beautiful dog.

Speaker 1: Yeah, I saw that.

Speaker 2: 6 years old

Speaker 1: What’s his or her name?

Speaker 2: His, its Shanty. He’s a rescue. Yes. Black lab rescue from Miami. He came from Miami with us.

Speaker 1: Does he have a lot of energy?

Speaker 2: Yes. I love dogs. I love animals. I trained him myself. So he knows that inside the house is, it has to be mellow.

Speaker 1: Alright. We have a few more questions then we’ll be closing out. But. So what’s your favorite thing about being part of the Harrisonburg community?

Speaker 2: I would say probably friendly.

Speaker 1: People are so nice here. I’m from Jersey and everyone is so mean up there.

Speaker 2: Again, one particular event that happened when we moved in, uh, we moved in September in 2015. The first Thanksgiving were completely alone. No, we didn’t know anybody. What happened was we drove by on that first trip, a year later we just took one of the cars, putting it on a train, came here. Getting into this office just randomly, rent the property from them and two weeks after just move all the stuff together here, so we didn’t know anybody. So we’re completed by ourselves. Thanksgiving we went to Food Lion and we were willing to buy a turkey breast because only two person. And the guy that was on the shelves in Food Lion took probably 10 minutes to explain us where to go to get it from, Carlisle, or Geroge, i do not remember which one, the outlet, a business that they have, the store that they have. So he took the time to explain and details, in this this corner this is Sheetz, on the left, whatever it is on the right. They really took care and make sure that we were pointed in the right direction. And that was great.

Speaker 1: You don’t see that everywhere.

Speaker 2: No no, I mean if it was Miami they’ll probably tell you “I mean, go to the store”. In Jersey, they’ll probably just ignore you basically

Speaker 3: Half the time you just get no response.

Speaker 2: So that’s the main thing. Being a basically a small city, you know everybody. I mean I, I know people all around and being here only three years. So that’s the main, the main thing you have friends all over and that helps, really.

Speaker 3: What does your community, do you guys do any game nights like for example, or like getting together for any holidays?

Speaker 2: Yes, yes. Uh, we, we are always getting together for, I would say probably once a month just for fun. Having dinner in different places. We have a group of, I would say probably seven to eight couples, kids, dogs and just get together, have dinner, or probably go to a salsa night in the cross keys vineyard. I don’t dance, but my wife does.

Speaker 1: It’s always just fun to listen to it though. Salsa music gets you up

Speaker 2: Yeah, completely. I mean, again my wife is an immigrant, she’s from Colombia so she dances and she loves to dance. I can’t and I don’t want to learn, but I can take her.

Speaker 1: You definitely could haha

Speaker 2: I probably could, but I know I don’t like it.It’s not gonna happen.

Speaker 1: All right. So we’ll make this our last question for this. Um, so, uh, for anyone I guess that it’s thinking about like leaving their country or wants to make that leap of faith to come to America or any country really, uh, what words of advice would you give to them in making that, I guess, jump? Like looking back on your experience.

Speaker 2: Looking back, I will always try to get a helping hand in advance. Try to know where I’m going to land and if there’s going to be uh plan B, let’s say.

Speaker 1: Yeah, so don’t just like put all your eggs in one basket and then you can’t?

Speaker 2: Yes, yes, yes. Try to see, uh, what was, what was going to be the plan. Of course everything can change and going back again. Mostly, I mean, some friends back home will ask you, what are you going to be doing? Uh, I cooked pizza for probably two years here. “Why are you doing it in Miami and not doing it back in Argentina?” Because, well, doing this here, I can live. In Argentina, no. That’s the big difference. From as less as I get paid and what he said, “are you going to go and wash dishes for the gringos over there. Why?” Because if I’m doing the dishes, I can live with that money. I can know that I can pay my rent and keep $100 at the end of the month if I want to. I’m not going to be able to do it or project back in Argentina in South America because it’s, you don’t know what’s gonna happen.

Speaker 1: So have a backup plan, have like the resources here?

Speaker 2: Get something in advanced , get something that you could rely on. And that being, if you have someone that can point you in the right direction, uh, that will make a big difference. Big Difference.

Speaker 3: Okay wait actually one more last. Is there anything you wish or should have done differently in your process of coming here, becoming a citizen, anything?

Speaker 1: Or no regrets?

Speaker 2: No, I mean, but that’s my way of life basically. I did what I thought it was right at the moment and if I made a mistake, I admit it. That’s it. But it was part of the process,yes

Speaker 1: *interjection* And you learned?

Speaker 2: Yes, of defining where I’m going to go next. *pause* No, I wouldn’t change anything. I mean, again, that’s basically my way of life. I mean, I did it at the moment, I took my time, I thought about it, I thought this was the best, and if it wasn’t, okay, next. Then try to change it. But, but uh, no, change no, no, no, no. I wouldn’t change.

Speaker 1: You wouldn’t be here right now you know.

Speaker 2: Exactly. Probably wouldn’t meet my wife or get the dog that I have now. I mean you can do a lot of different. I would probably be more smart with money, uh, at the beginning because, I was doing really good in Miami at one point and living a really good life. I mean I won’t regret I won’t change it, but if I did different I will probably be able to stay on track instead of having to downsize and selling the house, return a leased car, all the kind of things that you see easy when you have the money or,I mean, all the advantages that you have being able to live here. For us coming from the, from, from South America, it’s a bit easier now. Now I can lease a Mercedes Benz for $400 a month. That’s cheap basically. I mean there’s a lot of money, but it’s cheap. Okay let’s get it. I mean, why? I mean if you’re saving $500 at the end of month after paying the car. Yes? Well, okay, you probably can afford it, but if you are not saving the money? Uh, no, why didn’t you get a Corolla and pay 200? Is it basically the same? So that’s the only thing that I’d probably change. Uh, because as soon as you start, start doing better with money, growing, you usually start to spend more and that’s the end of it. At one point it’s going to be, yes, you’re going to pay for it.

Speaker 1&3: Yeah. True. All right. Thank you so much.

Speaker 2: No problem! My pleasure.

Loading...

Loading...