Migration from Colombia: My Interview With Fernando Gamboa

Interview with Fernando Gamboa

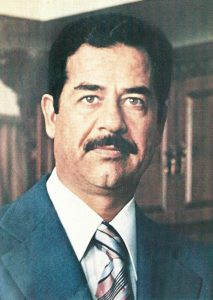

My interview with Fernando Gamboa was among one of the more memorable academic events that I was blessed to have while in attendance at James Madison University. During my time with Fernando Gamboa, I learned a lot about his migration to the United States of America from Colombia. Throughout the interview, I gained valuable insight into the views and opinions of one of this state’s—and this country’s—many Latino immigrants. I will divide the rest of this text into several distinct sections to help explain his journey and views as an immigrant living in America. This particular interview occurred on March 12, 2018 on the campus of James Madison University.

Migration and Cause(s):

Fernando Gamboa left his hometown of Bucaramanga, Colombia following the footsteps of his father in February of 2001(Where-is-Bucaramanga-map-Colombia.jpg). His father left in search of better economic opportunities here, securing an H-1B visa to work in the United States. He was a systems engineer and technician back in Colombia and found work through one of his relatives by working at their local travel agency. While Fernando and his family left Colombia in seek of better economic opportunities, some fled due to the violence of the Colombian drug cartels. These cartels, along with the communist Colombian paramilitary groups ELN and FARC,

“began target[ing] the civilian population during the 1990s through mass execution, enforced disappearances, mass displacement, and torture. Additionally, the conglomerate of paramilitary groups, AUC, [was] involved in drug trafficking and [had] committed numerous human rights abuses, including sexual violence against women, restrictions of freedom of movement and recruitment of child soldiers.” [1]

This forced many people to find a safer home in other nations.

Religion:

In my interview, Fernando Gamboa told me that he was not practicing a religion, and thus was not religious. He told me that his family grew up Catholic and that he was briefly raised Catholic, but that he no longer practices a religion. However, he still says that he participated, and participates today, in occasional religious activities with his family.

Education:

Fernando Gamboa was five when he arrived in Harrisonburg, Virginia. His formal schooling began here. He was a public school student of Harrisonburg. He states that his experience in this school atmosphere was enjoyable and for the most part, unproblematic. After reading an article entitled, “‘Just Like Me’: How Immigrant Students Experience a U.S. High School,” I think that he may have had a better experience in a school teaching English through collaborating with other students who may have been in a similar situation. As Jennifer McCloud states in this article, “[p]artnering within someone ‘just like [them]’ [is] significant,” as it helps to construct “relationships with other English language learners.”[2] Most importantly, this gives these students the unique “opportunity…to enter into the school’s social and institutional context as English language learners.”[3] This may have played a small role for Fernando as he was very young when he started to learn English. Yet, it may have played a much larger role for those incoming student-immigrants who needed help or for those who are currently in the ESL programs. Fernando could have provided this type of assistance to help these non-English speakers learn the language.

Policies:

In regards to policies on immigration, Fernando believes that the United States government should abandon institutions like ICE and the Border Patrol. He believes that the actions of these groups have become increasingly violent and too powerful. He states that ICE can detain people for over twenty-four hours with no reason or questions asked. He believes in a more open form of immigration as a better and easier path to citizenship. Also, soon after he arrived in the United States, the September 11 attacks happened. These attacks greatly changed the policies of the United States. Under the Bush administration, the 2001 Patriot Act and the DHS “imposed significant hardships on the millions of people who have applied for entry into the United States, or who have already gained entry.”[4](sand-dune-fence.jpg)

Racism and Discrimination:

After asking if there were any racist encounters between him and other Americans, Fernando responded that there was one particular occasion after 9/11 where he and his father were encountered by a man who inappropriately and intrusively asked Fernando’s father about his identity. He also remembered attending a rally in which racism was prevalent. While these are the only two encounters that he recollected on the day of the interview, he believes that the United States is still an incredibly racist nation that it has been exclusive of non-white people, such as the majority of the Latino community. He also finds it very problematic that some people are rounded up by ICE simply because they look brown or appear undocumented.

[1] Whitney Drake, “Disparate Treatment: A Comparison of United States Immigration Policies Toward Asylum-Seekers And Refugees From Colombia and Mexico,” Texas Hispanic Journal of Law and Policy 20 (2014): 132.

[2] Jennifer McCloud, “’Just Like Me’: How Immigrant Students Experience a U.S. High School,” The High School Journal 98, no.3 (2015): 269.

[3] McCloud, 269.

[4] Thomas W. Donovan, “Immigration Policy Changes After 9/11: Some Intended and Unintended Consequences,” The Social Policy Journal 4, no. 1 (2005): 34.

William Finch: Today I’m here with Fernando Gamboa, interviewing him. It’s 5:20, March 12th, 2018.

Finch: Hi, Fernando. How are you?

Fernando Gamboa: I’m doing well. How are you?

Finch: Pretty good. Pretty good. Now, can you tell me your name, age and, uh, where you’re from?

Gamboa: Um, I’m Fernando Gamboa. I’m, uh, 22. Uh, I grew up in Harrisonburg, um, but I’m from Colombia.

Finch: You’re from Colombia. Now what part of Colombia?

Gmaboa: Uh, Bucaramanga. It’s like a city in Santander, which is like the department, I think is what they’re called.

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: …the state.

Finch: Okay. Now, what about your childhood, now. Where were you, were you educated originally in Colombia, were you educated primarily here?

Gamboa: Um, I guess like I’m, I came here when I was five, um, so I went to like preschool and like, that’s about it in Colombia, and then I just went to like Harrisonburg City schools and now I’m here.

Finch: Okay. All right. And, uh, did you grow up with a religion, if you don’t mind me asking? Um, are you still religious, do you still practice that religion?

Gamboa: Um, I am not. So I do not. Um, my family, I guess, is Catholic, like a bunch of peo- like a bunch of, I guess, Latinx people are. Um, and I guess I was like raised Catholic. Like I went to church, um, up until I was like halfway through high school then I jettisoned the whole like religion thing…um, my parents are like, what I, I generally like to call it Catholic light.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: They just only sometimes do church things, ’cause a lot of other stuff gets in the way.

Finch: Okay. All right. And how did you come to the United States?

Gamboa: Um, we flew here in 2001. Um, my dad had a specialty workers visa, it’s one of like the H … is it like the H-1B, I think is what it was. Um, and then we were like on the, I guess like adjacent visas, it’s like H, H-something, for like spouses and dependents. Um, and so like we flew here February 2001…and yeah.

Finch: And can you explain those, those visas? I mean, what are the different types of visas-

Gamboa: Um …

Finch: … for those who don’t know?

Gamboa: I guess, um…H1 is a specialty workers’ visa. Um, so it’s like…I guess, yeah. I guess special workers’ visas are for like computer jobs and stuff,and there are other types of visas, there are visas for, um, people who are like part of like the judicial, like, stuff if they’re like a victim of a, a crime, there’s visas for, like, celebrities, there’s a bunch of different kinds of visas, I guess. I’m not super well versed.

Finch: Okay. All right. And, uh, did you live, you know, somewhere else before Harrisonburg when you, when you came to the United States or was Harrisonburg the first location that you went to?

Gamboa: Um, no, so like we came here right away. Um, my dad had, or has I guess, my godfather, it’s like my godfather’s cousin’s husband owned, owns, I guess owned, ’cause that company is no longer around, owned the company that my dad, uh, started working for. He came here on a tourism visa, found a job and then we came here follow, uh, like, following him after. Um, he, like, changed his visa status-

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: … from tourism to like the specialty workers’.

Finch: And what was that job, if you don’t mind me asking you?

Gamboa: Um, it was something to do with old, like, real–time sharing, like vacation company that was around here. Um, and so, I think he like, he did something with computers ’cause he’s a systems engineer, um, er, back at home in Colombia, so, um, it was like working with the computer stuff.

Finch: Okay. All right. And, uh, I guess you’ve already, you’ve already answered most of this, but how did you end up finally here in Harrisonburg with the, your father.

(04:15) Gamboa: Yeah. So, my, yeah, my dad found, um, yeah he got that job, uh, or, yeah, got hired by that company while he was here on a tourism visa, um, and then we just kind of followed suit.

Finch: Right. Okay. And what was Harrisonburg like when you got here? What was it?

Gamboa: Um …

Finch: Was it friendly, hostile, was it …

Gamboa: I mean, I don’t, so I was like five-

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: … um, so it’s like kind of hard to sort of tell. Um, I mean, so like, when we first got here it was like before 9-11, obviously, ’cause it was, um, February 2001. Um, so it’s like kind of interesting to sort of like hear my parents talk about the, like, flying before that versus like then now, like flying afterwards and then some of like the, so like responses other people had to like brown bodies post 9-11, um, we were like in DC at some point and, um, my dad who’s just like, I don’t know, he’s like a brown dude with like curly black hair, um, some guy like stopped him and like demanded to know where he was from.

Finch: Wow.

Gamboa: ‘Cause he’s like, looked like, I don’t know, someone who could be like, potentially have been a terrorist. Um, so it’s like those sort of things, but that’s like, obviously not like Harrisonburg itself. Um, growing up and like the city schools and everything was like all right. Harrisonburg’s always like–there’s a lot of people of color here. Um, and, uh, I guess the way like the city is like, was sort of like built, it’s like there’s a huge Mennonite population like the Eastern, I think the Eastern Mennonite University does a lot of stuff of like, um, immigrants and it’s just sort of like a, this, like the people that prescribe to that religion to my understanding, are like this, those kinds of people are very like open and like welcoming to others. Um, I don’t know, it’s like a, just like a pretty nice place to be around.

Finch: So, in general, accepting.

Gamboa: Yeah.

Finch: Have there, have there been troubles, um, for you, I mean I kno- I know you mentioned your dad.

Gamboa: Um …

Finch: That encounter.

Gamboa: Yeah. I mean, like, personally not really other than like with trash people here at the University. Um, I remember there was like uh Senator Gutierrez, um, from, I think it was like some district in the Illinois, I don’t know, came here, um, to talk about, uh, immigration. We had a rally, uh, in Court Square with him there.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: And there was like some a**holes that like were being loud, like, while they were driving by. Like, nothing like super, at least to me like, to myself and my family have not experienced anything that’s like, um, viscerally violent.

Finch: Okay. All right.

Gamboa: …of our immigration status.

Finch: Right. Okay. Um, and currently do, do you hold a job right now-somewhere?

Gamboa: Mm-hmm. Yeah, I work at Staples. Um-

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: … uh, I worked at Martin’s before that, or at some point for two weeks. That was no fun.

Finch: *laughs*

Gamboa: Um, um, but no, yeah. I have a job.

Finch: And how have the … How have those jobs been, how … are there, are there other people of, um, Latino descent working those jobs or have those jobs?

Gamboa: Um, used to, there was like … I mean like, no. Uh, at least in my department at the store, I’m the only person of color. There’s a bunch of other white dudes that work there.

Finch: Wow.

Gamboa: Um, the staple, like the store at large has a bunch of, uh, people, I mean it goes in and out, just people like are hired and quit or going to do something else, but, um, our, like I think the general manager is Egyptian. Um, they’re, and they’re like, no, like some … yeah. There are just people of other ethnicities that work there. Um, not entirely sure of like everyone’s migration status-

Finch: *laughs*

Gamboa: … but I can, I’m like, I’m, I would be pretty confident to say I’m like the only non-citizen that works there.

(08:55) Finch: Hmm. And how has Harrisonburg changed since you moved here? Changed a lot?

Gamboa: Mmm, it’s gotten bigger. So like-

Finch: Bigger?

Gamboa: … yeah there’s a lot more people here. It’s like, sort of, like the whole overcrowding problem, like, the schools have right now. It’s gotten a lot bigger, it’s gotten a lot more brown. Um, there’s a, there’s a huge influx of like, uh, there’s a larger Kurdish population, um, that’s here, um, and like the demographic’s just like gotten, um, a lot more diverse. Um, when my brother graduated high school, um, like, I guess one of the things they talked on at the, his Commencement, uh, ceremony was that there are a l- like it’s over 100 countries or something that are represented at the high school. Um, most are like there’s a large percentage of students there that speak more than two languages.

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: Um, that are more than just English and Spanish. Like, the, um, a bunch of different dialects or like people that speak a bunch of, a lot of different languages. This is just a very diverse, um, city. And that’s the sort of interesting, sort of to see that juxtaposition between like Harrisonburg itself, and then like JMU, ’cause JMU is like very white, very rich…

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: …compared to like everyone outside the bubble.

Finch: Right. Um, and you mentioned that you’re part of the debate teams-is that right?

Gamboa: Mm-hmm.

Finch: Right, what, what other organizations are you’re part of right now?

Gamboa: Um, I, I guess I would say I’m in a JMU Feminist Collective, um, and then, but, I guess I’d like to be more involved with, uh, JMU NAACP Chapter, but, um, like work has gotten in the way of being able to go to General Body Meetings…um, I’m trying to think. I guess the Society of Physics Students. Um, that’s just sort of like if you’re in the major you’re in, with, in, that organization.

Finch: Okay. And so, I mean, I don’t know if you could answer this, but what are the plans for those organizations for the future, um, specifically more the, the cultural ones…

Gamboa: Yeah.

Finch: …and the political ones.

Gamboa: Sure, um, I guess the NAACP, I’m not entirely sure I’m not on Exec, I’m like a General Body member. Um, I’m not entirely sure what their sort of like mission is outside of JMU, um, I know they do a bunch of stuff- like sort of like outreachy sort of things, they do some community service, um, for Martin Luther King, there’s like a breakfast, they had, I think, like a … what’s it called? Like a, a gala sort of thing and festival for that, um, up- upcoming, they have, like, Image Awards, so like you sort of like nominate people for, um, in some essay competition, uh, for that. The Feminist Collective, that one’s a kind of interesting, um, they’re sort of like, I guess, figuring out how to be more, uh, like, sort of have more Praxis, instead of just sort of like sitting and theorizing or talking about things, um, trying to find more instances where, um, there’s like opportunity for doing things with the community or sort of, um, yeah, like making spaces more avai- uh, like accessible to people.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: Um, because right now it really is mostly just like a, like a meeting to go to, uh, once a week. Um, and there’s like some stuff like I know during Sex Positivity Week, we sell, like, penis and vulva pops, um, to sort of like promote sex positivity.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: Um, uh, for … In the past they’ve done like, um, things with the One Billion Rising on Valentine’s Day, which is a sort of like, uh, movement around, uh, the world against sexual assault. Um, I’m trying to think. When Project Condom comes around, um, we enter, I think, like, um, I don’t know, it’s like a fashion show where you build a costume out of condoms. Um, I made the one for last year, that was really fun. Um, I guess it’s a more, I think everyone is attempting to, like, sort of reach outside of JMU, but it’s just kind of hard.

Finch: Right.

(13:56) Gamboa: I think this is a sort of disconnect or sort of an, um, like a gap in people’s ability to do things more than just around them, because it’s like kind of hard to do that as just students.

Finch: Right. Right. Um, in more broader terms, what do you see as the future for, uh, the, the current Latino population that’s living here?

Gamboa: Um, I don’t know. So there’s a bunch of organizations, right, there is like GOSPUS um, which I think that was the Salvadorian organization, um, that does stuff, um, but I don’t know if there’s like, there’s like, I guess New Bridges Immigration Center, like there’s a lot of, um, a lot of st- a lot, a lot of like different organizations. I don’t know if they like, any one like central goal that anyone is like trying to go towards. Um-

Finch: Right.

Gamboa: It also like, I guess sort of problems I get, um, if it’s like questions about immigration that’s like sort of necessary to understand that, um, not all Latinx people are immigrants, not all immigrants are Latinx.

Finch: Okay.

(15:12) Gamboa: Um, ’cause they’re sort of like large, so there’s large groups of, um, mostly like, I well, not mostly, that’s like are Mexican, Americans that are like the border across them, right? Um, when, when the, you, like the southern border of the US got drawn, they were people who, it was Mexico, 55 of Mexico got turned into the US. It’s sort of like those people then became American by virtue of where they happened to be living at that time…um, and then, um, also sort of like, yeah, not all immigrants are Latinx and, um, it’s sort of like a problem and when people discuss immigrant issues and like the needs of immigrant or like the needs of immigrant populations, they sort of only ever focus on Latinx issues, because it’s like, yes, there is a lot of, Latin- a large of a large portion of Latinx, of immigrants are Latinx, but, um, there’s a host of issues that other communities, other people in the immigrant commun- in like immigrant communities face that aren’t addressed or like are focused on, because the overarching narrative is of that of like a Latinx immigrant.

Finch: Okay. Uh, this next question is … it starts kind of small but it’ll expand, um-

Gamboa: Mm-hmm.

Finch: So, what are the changes, um, that you currently like see in Harrisonburg and then, second part of the question is much broader, what are the changes you’d like to see, uh, in the nation in general, and you can speak on immigration if you want to, you can speak on any issue, um, that, that you think has affected you or those around you-

Gamboa: Mm-hmm.

Finch: … like that is really important to you.

Gamboa: Yeah. Um, I guess, I don’t know insofar as like Harrisonburg because there’s not, like, Harrisonburg is very much like a pro immigrant city, right?

Finch: Right.

Gamboa: Like those, um, I been, it would have been nice, or like nice to see, I guess, in like the current climate sort of like, things like moves to be more of like a sanctu- like, uh, things like becoming a sanctuary city. Um, and taking effects to do that…um, I think the more pressing issues like the sort of like nationwide, so like how policies change, right, so like, um, ideally, just like abandoning ICE and like border, and border patrol. I think those things are unnecessarily, um, violent and-

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: … kill people. Um-

Finch: Right.

Gamboa: … uh, sort of like ending deportations, um, sort of moving away from like citizenship as, um, the sort of barrier to be able to access public goods. So, um, yeah, like open migration sort of things. Um, because at the end of the day like, this is stolen land. It’s, um, I think really hypocritical for like white people to stand here and complain about immigration, because, um, they stole this country. Like, they kill- killed a bunch of people, um, in order to create this, um, this, like, this nation, um, and then, are then hurt because brown people come. Because at the end of the day, like, a bunch of that shit’s just like racism.

Finch: Yeah.

(18:40) Gamboa: Like, people are racist. Like, I think it’s really telling, um, uh, when like recently when South Africa sort of I guess voted to take back land that was taken from, like, Africans by f**kin- colonizers, um, that a bunch of like racist people want, uh, like special attention to be given to, um, white South Africans. It’s like, they only really care about them because they’re white, not because they’re like immigrants or that they even need anything, because at the end of the day the, those are the same people that were, that like, there are the colonizers, they’re the ones that caused all this f**k s**t to happen to people of color, um, around the world. So-

Finch: Yeah.

Gamboa: … and, uh, I guess as a nation like I would love for the US to stop being, I don’t know, I think it’s like unnecessarily an, a violent body that does f**k s**t abroad and domestically, um, to people of color all around the world. Um, I don’t know. I don’t like the US. The US is like-

Finch: There are a lot of problems here.

Gamboa: There are a s**t ton of problems.

Finch: Yeah.

Gamboa: Primarily caused by angry white dudes.

Finch: I would agree with that. Um, so I mean, adding to that, what do you think of the rhetoric, uh, specifically in terms of the, you know, regarding the issue of immigration in the public sphere? I know you sort of touching on this, um, if you want to add to that.

Gamboa: Um, I guess like the rhetoric that’s been used around immigration is sort of like a long sort of like, it was like, has been constructed to be that way, right, so like the sort of, um, the construction of like the criminal immigrant, the criminal immigrant? Yeah, like crimmigration, um, with like the categorization of an illegal immigrant since like the creation of the Chinese Exclusion Act, um, that sort of like creates a…cl- a classification of person that is not deserving of being here. Um, really based on them not having been born here or not coming here the right way…um, so like, sort of moving away from, like, calling people illegal, um, which is just like violence in and of itself, but then also that justifies a bunch of f**k s**t from happening. So like, it’s like Operation Blockade and, or Project Blockade an Operation Hold the Line, sort of like Clinton era, uh, border enforcement that happened along like border cities of San Diego and El Paso, so like in California and Texas, that sort of literally militarized the border and forced people to, um, stop crossing in urban areas and to go enforce it and sort of funnel them to the desert. The sort of ways that the like policymakers, uh, were talking about that as like sort of, um, prevention by deterrence, uh, sort of making it really difficult and dangerous for people to come into the country…uh and then sort of justifying the deaths of those people both, um, in the desert in Mexico, but also, uh, in the US by saying that they’re criminal and that there was just a necessary, that that’s just an inherent risk that they took coming into this country illegally, um, when those are just like artificial constructions because they don’t want brown people to be there or be here.

(22:19) Finch: Right. And adding to that, what, I mean, so out of curiosity, I’d like your opinion, your input on this. Uh, what do you think they should do about the border?

Gamboa: Um, get rid of that s**t-

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: … like a border is unnecessarily a violent institution. Um, yeah, no, like, I think the open borders, I think like the border fences, like … It is asinine to think that you can do that. It’s sort of misunderstanding of like how the geography and topography works-

Finch: Right.

Gamboa: … um, in the border lands, um, and like the Sou- yeah, in the south, like the south, the southern border of the US. Um, and sort of like the hyper, um, militarization that’s happened to it, like that s**t needs to go, right? Like get rid of border patrol. Um-

Finch: Seems to create a lot more violence.

Gamboa: It really does. It, um, kills a bunch of people, uh, that it doesn’t need to, and shit like getting rid of, or like preventing, there’s like militias, um, just like white dudes that have nothing to do, but like, attack brown people. They go around and round up people that look brown or look undocumented and will turn them in to ICE.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: And they ride around in like SUVs with like AKs, just like militarizing the border on their own accord outside of any sort of like governing body. I think that sort of stuff needs to not happen.

Finch: Okay. And I wouldn’t happen to be well versed on this, but is, does ICE have a large presence here in Harrisonburg?

Gamboa: Um-

Finch: …you can finish eating, don’t rush.

Gamboa: Um, there’s a … Yeah, there’s an ICE office here-

Finch: Okay.

Gamboa: … um, people have been picked up before. Uh, I know in the past there’s been a sort of like, ICE detainer that gets placed on someone so that, um, you can be held more than 24 hours after like being pulled over for something, and it gives, um, ICE the, like, time to be able to, like, check whether or not that person is in the country, um, like as, has like, is authorized to be in the country. Um, so there is that. Um, sometimes I know there’s been raids at, I think that poultry farms, like the poultry, uh, poultry processing plants that are around here. Um, but I personally have not seen like ICE agents. But then again, pigs look the same regardless of what they’re wearing. So.

Finch: Yeah, and they seem to, just from my understanding, from what I have discovered from class and that is, uh, we’ve watched, seems that this country continues to do that and then the people that they need working in these plantations or these, these farms, like these chicken factories and stuff like that happen to be people, uh, you know, some people of Latino descent who are willing to put in a lot more effort than-

Gamboa: Yeah.

Finch: … a lot of people here.

Gamboa: Yeah. I mean, white people don’t want those jobs. Um, they don’t think, they think they’re above it.

Finch: Right.

Gamboa: Um, and don’t do that. And that’s sort of like, it is a job that no one wants to do sort of like leads to exploitation of very vulnerable populations because they don’t-

Finch: Yeah.

Gamboa: … want to. Um, I guess I’m also not super big on a fan of like justifying having immigrants here to do jobs that white people don’t want to.

Finch: Mm-hmm.

(25:46) Gamboa: Um, was I, it’s like I don’t know if it was like post election or pre election, uh, what’s her name, well, Osbourne’s daughter, Kelly, whatever her name was. She was like, “Donald Trump, who’s going to wash your clothes if you deport all the undocu- like all undocumented people, something like that. And it’s just sort of like thinking that that’s the only thing we’re good for is like not the case. Um, like, we are not, we’re not here to be like sec-…second class citizens, not here to, um, do your laundry or pick your fruit or like kill your chickens. Um, so like here to f**king live.

Finch: Yeah.

Gamboa: Um, and sort of only wanting people to be here for those reasons, um, just, again, sort of like adds to the kinds of violences that we experience, because it then sort of … What happens to the people that aren’t willing or aren’t able to work low like, um, low skill jobs, or people that aren’t like the valedictorian from their high school that got into Harvard on a full ride? Right? It’s, there’s sort of like a gap between their deserving-ness, um, to be in the country.

Finch: Right. Yeah. It seems very, uh, seems very dehumanizing to consider immigrants as only, uh, yeah, people of exploitation.

Gamboa: Or a commodity. Yeah.

Finch: It seems like, it is very exploitive and, yeah, it’s awful to see that, uh, seem to be dehumanized very quickly when they come here.

Gamboa: Mm-hmm.

Finch: Um, so what would you like people to know, I mean, from this interview, from this story? Are there any final thoughts, um, any other opinions you want to share?

(27:36) Gamboa: *laughs*. Yeah. Um, I guess like things like the Dream Act are good insofar that, like, they have material benefits for people. But they’re bad insofar that it, again, sort of plays into like, uh, undeserving-ness or like an exceptionalism narrative of immigrants. Like the only people that deserve to be here are not just like the valedictorians or the people that are like working hard or came here of their own, like, not of their own accord, like, or against their will. Like the sort of people, like myself that, like, qualify for DACA stuff, right? Because those sorts of policies unnecessarily exclude people like our parents who should get to be here, because they worked super f**king hard to be here, um, and didn’t do anything, um, to not be here…other than like be born in a country that wasn’t this one and was honestly probably f**ked up by the US or other white people. Um, they’re like, a long process of colonialization, and like economic exploitation, like … right, so like, sort of moving away from those things and seeing like we are not free until everyone is free, um, and do stuff like that…Also, um, so like sort of, there’s an, I think there’s a, there’s a very strong need to sort of move past dreamer narratives and sort of like, “We are all Dreamers.” No, we are not all Dreamers. Um-

Finch: So what does that new narrative in your mind look like?

Gamboa: I, I just don’t …

Finch: Like the rhetoric of it?

Gamboa: … just like, I … I don’t know. I think that’s like, that’s like super layered-

Finch: Mm-hmm.

Gamboa: … right, ’cause I think it’s a product of, like a long history of colonialization that’s happened in this country. I don’t think that can-

Finch: Right.

(29:24) Gamboa: … I don’t think that necessarily can happen, um, without like fixing a bunch of other issues. Um, moving on from that, I guess it’s also important to like, I think vilify the Democratic Party, they don’t give a shit, they never have, they never will. Um, they didn’t, they don’t want to help us. The only thing they’re doing is seeing potential voters, uh, at the end of the line…um, like a bunch, or like, uh, like the sort of holding a ho- or attempting to hold the country hostage in order, um, in order to get a DACA deal, um and just not actually being able to do anything or not… pressing hard enough. They only care so much as to like be, do things that are put on paper, right, like Clinton was the one that passed a bunch of border security, or border security legislation in the ’90s. Obama deported a bunch of people, more than, I think like Clinton and Bush combined. Um, loved deporting women and children, um, he’s like a piece of s**t, like, it’s important to understand that no one at, like, I’m very hard pressed to believe that any politician actually cares about immigrants, um, because at the end of the day they don’t really have to, um, and we’re always sort of a population that is like pushed on to the sidelines. It’s like we have to do these things, and then we’ll figure out immigrants. But there is always something that gets pushed to the top of the docket before we’re ever considered in anything. Um, so it’s sort of like fore-fronting our needs and like people have to start caring about people as people, or like thinking it, seeing people as people before like they can do anything. Otherwise we’re just like the people who are going to clean your clothes and pick your, pick your fruit.

Finch: Yeah. It’s very problematic. Anything else you’d like to add?

Gamboa: I don’t think so.

Finch: Okay. All right. Well, this concludes my interview with, uh, Fernando Gamboa. This is William Finch, 5:50, March 12th, 2018.

Loading...

Loading...