Jake Adams: Hello my name is Jake Adams I am an undergraduate student and James Madison university and today I am sitting down with Alicia Horst, would you mind spelling that for anyone listening.?

Alicia Horst: Sure it’s ALICIA last name is HORST

Jake Adams: Thank you very much um today we are going to be discussing miss horses personal history so I want to begin with you tell me your age and you are some of your background

Alicia Horst: OK so I am 39, recently turned 39 arm was born in this town but moved away when I was an infant. About five months o OK so am I am 39, recently turned 39 arm was born in this town but moved away when I was an infant. About five months old. It’s kind of funny because I was born where JMU is now located

Jake Adams: Oh wow

Alicia Horst: Because that used to be the hospital one of the buildings um. I lived um until I was ready to go to high school I lived in southern Italy on the island of Sicily my entire education through middle school through eighth grade would’ve been in Italian, Moved here, and have often on been in the United States ever since did some time in South America some other locations. Travel has been a very important part of my life. But certainly I think that my childhood has definitely influenced who I am as a person. I lived in a place that is in the middle of um certain civilizations that would have been part of the Western influence so it was interesting as a child to live in a place… live on an island that had both Greek temples and also recent migrations from when the Eastern Bloc of Europe would’ve changed starting in ‘89, 1989. So it was a very formative experience, I guess I am who I am because of that.

Jake Adams: Thank you um your parents I understand to be Mennonite missionaries. Which is…

Alicia Horst: Yeah the worked with, they were religious workers? I guess? There was a church that started in the island (Sicily) after… the history is that in this area people sent packages, relief packages, to Sicily after WWII because of the bombing on the island it was pretty devastating. So people here would send bandages and packages to that area and after a while the people there asked who on earth was sending these up so it started this relationship with um between churches here and people on the island and eventually ended up in a church. So by the time my family moved there that would’ve been the case. So I was just a regular kid growing up in the schools with everyone else. All of.. most of my friends by far were not from the United States but um that’s the reason that my family moved there.

Jake Adams: Okay. Did you… I can tell you don’t have an accent. Was English your first language or was it…?

Alicia Horst: No actually. I’m not sure my parents, my mother in particular tried to speak in English at home, I would say that when I first moved to the United States I did have an accent but I lost it over time. My first language, the language i felt most comfortable interacting with definitely was not English growing up because all of my education was in another language and I think the brain tries to be as efficient as possible and you just use what you are most commonly using, but my mother would make it a point to speak to me in English so that I would understand it and she taught me how to read and write in English. But yeah really I didn’t start using it on a regular basis until I went to high school.

Jake Adams: Okay. Being a part of a religious organization, with parents who were heavily involved in something like that overseas, how did… what was your experience in a sort of religious relief community? You mentioned you were exposed to migrants from other areas like Eastern Europe and Northern Africa l, what was your experience like interacting with….

Alicia Horst: So my parents probably weren’t, their primary focus wasn’t probably in relief. That was the origin of it, but by the time they got there it was very like church-focused I would say. What I remember happening, when all of these events were going on in the Eastern Bloc and people started moving, they were taking like rafts basically to cross this area of the Med (Mediterranean) that is not very large but kind of rough to get to the island, was that there was just a lot of need for it there were these camps that were set up and so that made a huge impression on me as a child in a way that I don’t think my parents even realized because as an adult I’ve talked to them about it and yeah they have vague memories of it but for me it was like this huge deal. Just realizing that people make huge sacrifices and do things that place them in a completely unknown area where they are very vulnerable for the sake of either a new life or to flee danger. The North African community that was on the island would’ve been there the entire time I was there and probably still is. But a lot of the street vendors, people we would interact with on the beach would’ve been from North Africa mostly Tunisia, and Algeria, Morocco, those three countries. Yeah so it was very interesting when you’re in a space we’re there are people kind of traveling through on a regular basis. That was always a part of my childhood.

Jake Adams: So um you left Italy when you were 13 correct?

Alicia Horst: Yes

Jake Adams: I am interested… growing up I would imagine that you felt strongly, you identified strongly with Italian culture or Sicilian culture I guess.

Alicia Horst: Yeah my goal was to get away with not letting anybody know that I was from another place so unless they found out my last name, my first name is a little unusual, they wouldn’t use my first name there but they could pronounce it or whatever but that was my goal as a child, to just kind of be under the radar.

Jake Adams: Mhm do you know much about your family history as far as their coming to the US? What’s your lineage?

Alicia Horst: So it’s interesting because I think, I’m sort of intrigued by the idea of doing genetic testing only because l, I don’t think it’s necessarily like the end all be all, but because what I think what people always tell as family stories aren’t always accurate. So what I know of my family history is that there would’ve been people fleeing religious persecution in the like 17th century probably mostly. And would have eventually come because of William Penn’s recruitment of people providing religious freedom and land, that was not his to give, but there we go.

Jake Adams: Yeah

Alicia Horst: That’s the history so um to my knowledge that’s the original way that most of my ancestors would’ve come to the United States but I… I’ve wondered at times if I might not have some history of middle eastern background and don’t have any specific way or demonstrating that but just because of some of the stories that I’ve heard

Jake Adams: Yeah that’s really interesting. How was the transition back to America or I guess to America for the first time for you? Did you… how was assimilation? I imagine you probably spoke English pretty well.

Alicia Horst: Yeah I spoke it, not comfortably I would say but I did speak it so I did within a few months I felt fairly comfortable. There are still words that will trip me up because context is so important so you know when you read something in a book versus how people use a word colloquially I still have to sometimes ask for clarification. English is such a complex language to begin with. It has so much vocabulary that anybody that is sort of interacting with it for the first time a lot is going to encounter some type of difficulty along the way no matter how fluent you are. I think the main struggle for me was social moving here. I think that the way that relationships are built in the United… well I should not say everywhere in the United States but certainly were I was in the valley versus being in a really large, for me it was decently large city of a million at the time. It was a little shocking especially because Italians are very communal, Sicilians are very communal. There was not nearly as much emphasis on people being in or out of social groups and that seems to be a huge identity factor in the us like clicks and in high school that would’ve been the reality and the way that’s defined is by particular interests there are all of these social boundaries that are created and are fascinating now that i look back but um yeah for me academics were easy because the system i grew up in was very demanding and i don’t know language ended up being pretty easy. It’s something that I’ve heard from many people who come into this office as well that you learn how to eventually work with some of the systems but the loneliness that is inherent in the american culture that can happen in the US is really difficult for people bc the US places so much emphasis on mobility and independence it creates situations where people. It’s one of the factors contributing to people feeling like relationships are not nearly as important and not as much priority is placed on that and so you have to go out of your way to kind of follow a community of people. Its very countercultural to do that here

Jake Adams: Yeah so when you came back you came back to harrisonburg or the valley area?

Alicia Horst: The valley are a yeah i wasn’t always.. I went to school in harrisonburg but sometimes i was traveling to harrisonburg.

Jake Adams: Mhm I would imagine that with the position your parents were in, coming back to the US was there like a social circle or social network within the church that you participated in coming back?

Alicia Horst: My parents certainly, yeah would’ve been connected to that environment and i was too i think for a period of time certainly in high school and that was a way for me to have some connections though culturally so i had a way to be around people that culturally wasn’t always super comfortable for me yeah and so at the time i think that that would’ve been an accurate description

Jake Adams: So after high school you went to school, where did you go to school?

Alicia Horst: My family moved for the first year we were in harrisonburg. I had 3 brothers and we started to go to schools here in harrisonburg that are mennonite affiliated so i have an older brother who went to what is now eastern Mennonite University and we would’ve gone to Eastern Mennonite High SChool? The names have changed a bit. So i went there four years. I have brothers who went for different amounts of time but

Jake Adams: So what was your major or what did you study?

Alicia Horst: So the high school was… I eventually studied social work and later went back and studied a combination of theology and what they call spiritual formation. So the combination of studying social work was important to me because i had spent a lot of time in South America and specifically i worked with a group of children’s homes and realized i had a lot of learning to do (laughter)

Jake Adams: Where in South America?

Alicia Horst: I was in Venezuela. This would’ve been about twenty years ago. So that was a good learning experience for me. I learned a lot about the stuff… interacting with the staff of the homes. I eventually went to grad school to figure out more about what i grew up around. It was more of a selfish reason i think. I wanted to figure out what all these belief systems were about and how that affects how people move in the world. But my profession, my work has always been social work.

Jake Adams: Okay, did you struggle with that?

Alicia Horst: With social work?

Jake Adams: With the decision to focus on social work.

Alicia Horst: Yeah! I didn’t declare until like the middle of my junior year which is horrible but I’ve always been a very curious person so to have to focus on one thing was awful. I ended up taking a year off, a year off in south america was in between my second and third year of university and i did that because i was having the hardest time deciding what to major in. i think part of it was also that i went to university young. I was seventeen because in the Italian school system it was a normal thing to be younger than it would be in the US. So i ended up taking a year off and i think my decision was influenced by both my experience in south America but also that I tend to be a person who can be very interested in ideas I wanted to have some kind of practical application so i wanted to be able to get a job after i graduated from university otherwise i knew id try to be in school for a really long long time and that’s just completely unaffordable.

Jake Adams: Well that’s really interesting because i know as an undergrad it’s kind of hard sometimes to figure out decisions that impact the rest of your life.

Alicia Horst: No seriously and there are so many professions these days that require you to go to grad school before you can do anything and so it is a definite challenge.

Jake Adams: Yeah so after graduate school. So at this point you’ve looked and theology and religion. What was your mindset leaving grad school? What was your ambition?

Alicia Horst: Before i went to grad school i would have worked in two different state jobs. One was in a psychiatric facility were i was serving as an interpreter and working with a psychiatry team and then i worked in child services and i realized that type of system is not ideal for who i am in terms of the way that policy is written for interacting with families. That was before grad school and after grad school i knew that i wanted to focus on other kinds of work, community based organizations and nonprofits. That’s what led me into… i wasn’t necessarily sure that i wanted to stay in Harrisonburg but there was a large need for bilingual people in this town and so that’s what led me to stay. Some of it was circumstantial and some of it was… there was work that was connected to things i cared about. So after grad school there was a grant that Big Brothers Big Sisters had gotten to work with children whose parents were in prison and so i was working with that and with families who spoke multiple languages. I worked with federal grants at the time and that was important to me because i’m a mission driven person. So working for an organization that wanted to support kids who had experienced a lot. So that’s what i did before coming here.

Jake Adams: So then when did you meet Susannah Lepley, the founder of New Bridges?

Alicia Horst: I think i first met her right after I would have graduated from university. About the time i graduated undergrad was about the time this agency would’ve been starting. I think i first met her because i was checking out this agency as a possible location for my undergrad practicum, if i remember correctly.

Jake Adams: I know you speak Spanish.

Alicia Horst: Right

Jake Adams: When did you i guess…

Alicia Horst: When did I learn that?

Jake Adams: … learn Spanish?

Alicia Horst: So when i went to university there was this amazing professor. I’ve never encountered anyone who can teach as well as she could before or since. So it helped that spanish has a lot of similarities to italian, they are close languages so i understood the grammatical concepts behind spanish. I studied that for two years it was an intense two years with her. Then i was in south america

Jake Adams: Well I want to talk about New Bridges.

Alicia Horst: Okay

Jake Adams: Obviously you are the executive director of New Bridges currently

Alicia Horst: Its a small agency so that title is not big but yes there you go

Jake Adams: Alright I lied, before we talk about New Bridges I know that you’re an accredited representative through the DOJ’s office of legal access programs

Alicia Horst: Yes

Jake Adams: Their program that allows qualified non-attorney individuals to represent immigration matters.

Alicia Horst: Its essentially an attorney but for immigration matters

Jake Adams: Is that through New Bridges or did you do that before?

Alicia Horst: It has to be through an agency. So when i started that program it was tricky because the agency needs to be recognized by this program. It used to be under a different agency, still connected to the DOJ so in order for someone to be accredited you had to be connected to a recognized agency so i had to get the agency recognized at the same time as I was applying for accreditation. The agency cannot be recognized without an accredited representative and you can’t be accredited without being a recognized agency. So yeah that was the year 2013, was dedicated to that and there are two of us now that are accredited. I have a coworker that just got his accreditation in December

Jake Adams: Okay well then moving into New Bridges, how did you first get involved?

Alicia Horst: I was a volunteer a bit for them when they would have been using volunteers I didn’t connect as much to the actual office. I think they had a couple of events i would have helped at. But I’d always heard about it. One of my social work professors when i was in university was one of the people who helped set up the agency when they were first thinking about how to set this agency up so i would hear about it in my social work classes. And as i was interacting with Susan over time, she would’ve been the director here for about 9 years, yeah so at the time a lot of people would’ve known her for her work.

Jake Adams: What is she like?

Alicia Horst: She is an entrepreneur. She has a lot of ideas and she loves to make those happen and that’s part of who she is. She likes to see what might be of benefit to the community and works to see that happen. Since she’s worked here she’s worked at a number of different positions. She’s now working for Sentara the medical hospital

Jake Adams: Oh okay

Alicia Horst: But she’s worked at both universities

Jake Adams: So What was your career path here? You started volunteering for their community programs but…

Alicia Horst: Right I think it was somewhat of an indirect path i would say. A lot of my work before coming here focused on multilingual family work so by the time i would have started conversations about the position here i would have been doing work in mental health and child welfare and in grant management, implementation types of questions and program management, all in a multilingual capacity. I wasn’t doing as broad a base of services as New Bridge provides but there were elements of that. For example, my approach to a situation in which a family might have some stressors there wouldn’t be some questions about the child’s well-being, I would go about asking questions about how to support the family itself so it’s a little different because I’m familiar somewhat with what the system used to be like. So i think the things i had to learn more about as it relates to the work here have to do more with fundraising because we are not funded by large federal grants so when you have mostly private funding like we do then you have to think about that.

Jake Adams: You’ve mentioned that the experiences you had in mental health systems and welfare systems, i guess more state experiences you didn’t really enjoy the work that was more bureaucratic?

Alicia Horst: Yeah and it’s very specific. There is not as much room for creativity when you’re problem solving

Jake Adams: How then did you go from there to interacting with the mission statement, and in this response could you illustrate the mission of New Bridges and what it is meant to be and how its unique from more bureaucratic, policy-centered relief systems.

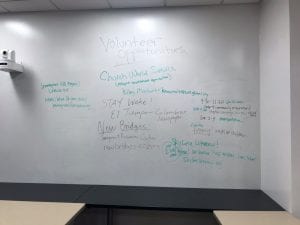

Alicia Horst: Yeah just the fact that we have the capacity to change our mission statement as an agency is in itself going to be a little different than a state system where its going through legislation to create policy and the mandate of whatever those agencies happen to be. The mission here, so we went through strategic planning a few years ago, which is a normal thing that nonprofits do to focus their work for a chunk of time. The election happened after we did that, like month or so after that the election happened so it’s interesting to think a guiding document that was created before our current context. We have the power to change it and we tweak things. A lot of it still is relevant but they changed the mission statement to read “engaging immigrants, connecting cultures, and building community” and i find that we are so focused right now on connecting with immigrants, that first part of it, that (we need to) remember that greater community building is what i have to keep focusing my energy on not forgetting because when you’re in the middle of a crisis like the one that people are experiencing right now, if you’re an immigrant it’s… we are in a crisis right now. (laughter)

Jake Adams: Yeah

Alicia Horst: Yeah it’s good to have that, those kind of guiding statements cause it help you to realize that there’s a bigger picture. We do live in a community the harrisonburg community is one where a lot of people care deeply about the identity that has formed of being a place that is multicultural and wanting to support multilingual education, wanting to have an environment where children grow up together to care about each other. Those kinds of things i think are something that they put a lot of energy and resources toward. I realize that all of this thats happening at a federal level we are experiencing at a local level quite differently than other communities might around the country, but nevertheless its at a time like this where there’s even more need for people to know each other. So we aren’t depending on certain sources of media to form how we interact with each other

Jake Adams: Just to clarify, the situation American immigration is in is following the 2016 election where Donald Trump won running on a pretty anti-immigrant campaign i would say.

Alicia Horst: Yes

Jake Adams: He in March, it was March right? That he ended or claimed it was his intention to end the DACA program?

Evan: September

Alicia Horst: It was September and they (immigrants) had a month window

Evan: They stopped taking applicants in september and then it expires in March

Alicia Horst: So anybody that had expiration for their DACA protection before March 5th could renew it. They were accepting renewal applications for those six months

Evan: but currently the Supreme Court is refusing to hear the case so…

Jake Adams: Yeah there have been court delays to that action

Alicia Horst: So there were two injunctions. The one in California is the one that opened in back up in that sense by saying although you have the authority to do it your legal rational is not sound and therefore renewals can continue. The initial one is still not proceeding, so people that are 15 years old and meet all the requirements cant apply for deferred action it’s only people that were already a part of this program that can continue to renew

Jake Adams: With your position in this organization, especially in a community like harrisonburg where we have a large immigrant community relative to its size. What has been your experience with how people in our community have been affected by this?

Alicia Horst: If you can imagine what it’s like to be a person a younger person who has had no control over where they’ve lived their entire lives. It’s not like a child says “alright im gonna up and go” I mean there is an unaccompanied minor phenomenon that happened but these are not usually the case for people who have deferred action. So you’ve invested your life in living in this place its home, it feels like home. I know what that’s like as a US citizen in another place. And so the inverse, people living here feel like they are just as connected to life here and your entire logistical thing of making life happen well are depending on a program that is at the whim of politicians. Your capacity to have in state tuition, get a job, drive a car with a license, all those things are dependent on you being set up for two years. So every two years you’re having to pay fees and make sure you get the stuff in on time and they’re processing things slowly, it’s just a mess. It’s incredibly exhausting. I had people who had to make a decision because their expiration was in March, but it was after march 5th. Do they try to apply? They decided to do it, and they got denied. Now it’s open again, so they have to you know try all over again. It’s this back and forth thing in the middle of already trying to manage a lot in life. Like if you think about how stressful it is for you to be a university student, imagine all of your responsibilities related to all of that and it’s just another layer of stress and unknown as you’re trying to plan out your life, you know? And it sucks, it’s just a lot and talk about anxiety. When you have to make some really big decision about if you had another means to become eventually a resident that might involve having to travel outside of the US to your country of origin, that you don’t remember, and have to go through the consulate process that’s complicated, that you have no knowledge of. It’s just… the strength people have to go through all of that is just absolutely mind-boggling yeah? Cause its stuff that most people don’t even comprehend. Most people in the united states don’t really fit in to the immigration system at all. That’s just DACA, there are all these other things happening w/ immigration right now that are just… yeah… and the stupid thing about it is that the dream act has been a really big thing for congress to do something about and many generations, for 10 years, i mean it’s been since 2007 that they’ve been doing it? Um… there have been times when it almost made it by, like 5 votes…. It’s ridiculous, i mean it’s high time that we figure this out, i mean for the benefit of our society. When people have already demonstrated by the way… and you can see it b/c our immigration system requires it, so it’s even documented that people are committing crimes because u have to fingerprint people… so its like…you can even have proof

Jake Adams: So i wanna ask u… i think that right now USA is sort of dealing w/ a problem that’s a lot bigger than the dream act or DACA and it isn’t necessarily how we feel about illegal or undocumented immigrants from latin america or mexico, but how the american identity interacts w/ immigrants as a concept.

Alicia Horst: I should also say that in this particular area, the dream act and daca are mostly connected to latin americans but there are other ppl/communities in the US where it would be korean, um, like so, yeah, so i just broaden that out depending on what focus youre talking about

Jake Adams: In this sort of identity debate about what USa should be regarding immigration, and approaching the concept, there is a lot of rhetoric thrown out on both sides about from the adimitrations, from media, how do u think that general rhetoric surrounding immigration, how accurate it is?

Alicia Horst: Generally speaking, so most of the opinions i’ve hear are really hard for me to listen to b/c they aren’t even based on fact. Um, like a lot of ppl are talking about things they know nothing of, like they really honestly don’t know immigration policy, so when they’re talking about things like chain migration they aren’t even aware of the types of relationships w/in a family that can even bring another family member. So i don’t know if they’re just trying to just exaggerate to make a point or whatever, but if they actually knew uh who a us citizen can petition for a who a resident can petition for, and how long it takes for those things to happen, um i mean if a citizen wants to bring a brother or sister if they are from particular countries it can range from 15-25 years, before a visa is even available for that relationship. So, um, cousins, aunts and uncles, you cannot petition for them no matter what kind of um status u have and things get just discussed in a way that is um… it becomes so much, i mean we talk a lot about the fact that really data is irrelevant when it comes to these kinds of conversations b/c it’s about fear and prejudice really so no matter how much… cause i’ve tried i’ve ever shown people how long people that are petitioning have to wait for visas before they are available for that person. And it’s as if that information is irrelevant really, that’s how people are bringing it up to begin w/ as being the issue. We don’t realize that behind that is something entirely different. Those are just rhetorical tools that have nothing to do w/ the motivation behind um why ppl have certain opinions. And that, is i think we’re the real work is in this country, it’s gonna take forever. We as a country have been its founded on racist principles in my opinion and our economic system depends on a lot of factors that create dynamics that are really difficult to address when it comes to talking about justice and immigration. SO, i dunno what to tell you it’s really hard to listen to the media.

Jake Adams: It’s been a trend i know, as a student of immigration history, um,

Alicia Horst: I know its historical. It’s nothing new right? You can look up stuff from 100 years ago it looks the same you just switch to persons from eastern europe instead or italians versus like… I know that. It doesn’t make it any better though

Jake Adams: It’s tough, it’s a hard system to address. What in your experience in immigration or as a social worker in harrisonburg in for the past several years, what changes have you seen? I know we were talking about nationally I think there has been very unfortunate shift in the discussion of immigrants, but how do you think the national shift is reflective of how harrisonburg as a community has changed over the past several decades…

Alicia Horst: Like how does harrisonburg reflect what’s going on nationally? Or…

Jake Adams: Yeah I guess that question and more broadly, what changes have you noticed in the harrisonburg community over the past several years as a social worker and immigrant advocate

Alicia Horst: So i think the way that people were talking about, for example, building a second high school was hard to see at the local level because i think that some people were misinformed about all of the different reasons why there was population growth. Some of which has bee immigration, some of it has not. But to kind of focus in in on immigrants being the reason that there is a need for a second high school. First of all, if it were the actual reason then why not build a second high school? And secondly, I actually don’t think it was necessarily connected to accurate data. So that was an interesting dynamic locally that has happened… most of the conversation has happened since the election. I mean people knew this was coming, that this conversation would have to happen before the election, but yeah i think that its taken more energy recently because of the election. So when i first encountered Harrisonburg, that i can’t remember in high school, it was in the early 90s. It was a different town. I think that the poultry, there were a lot of growers there always have been. This is a rural community with lots of farms for a long time, but the shift to poultry processing plants and that kind of stuff really happened in the late 80s, early 90s, the mid 90s. The industry changed, um, lots of ppl decided to stay that had initially been ppl that would have been doing migrant labor, um, a lot of refugees started coming from the former soviet union during that time, and then in the late 90s there were a lots of curds that came and so, yeah, i mean harrisonburg has changed in many ways over the last 20 years. And it’s an interesting dynamic, when I was interacting w/ some folks, in the department of labor they would just be like “it’s just fascinating to us b/c the demographics of this town are percentage-wise very similar to what they would have in NOVA (a very very large, much more urban community) and they they suddenly have this small city that has this level of diversity, and for them it was an enigma, like “whyyyy” ya know? But i think there’s all this like confluence of factors, both the industry and the fact that there was a receiving community… there were ppl that were interested, either for religious reasons or others, were interested in supporting new arrivals from other countries. So, whatever the case was, this is a town that ppl felt comfortable staying in so its unusual to have a town this size be this diverse and yet its worked! And its maturing and its understanding of its identity. I think there’s a lot of work still to be done in terms of having different groups of people interacting w/ each other so its ya know, the town is evolving in its own way but i’m certainly glad to live here… even though there’s a lot of work to be done, i feel a lot of gratitude that Harrisonburg is what it is right now in this moment in time in terms of what’s going on nationally versus what’s going on here.

Jake Adams: I know, as a student, at JMU there are a lot of opportunities, events centered around activism and sort of disagreeing w/ a lot of the rhetoric that has been pushed regarding immigrants and their entire identity as ppl. And so, i guess noting the changes you’ve seen in the harrisonburg community, how has um, how have u perceived activism, or i guess a renewed motivation for this type of immigrant work? Have you noticed the community reaching out in a way that is different than before as a response to unfair rhetoric?

Alicia Horst: Yeah, I think um, i mean its been going on since before the election. But this is certainly a town that, you see the little welcome sign that you see places that’s become spread around nationally, that comes from this town originally, and there are also ppl that have been very connected to refugee issues and connecting and supporting refugee families. So i think yeah there are public demonstrations that have happened after specific decisions were made very quickly- ppl would show up in court square and there’d be a lot of storytelling going on and just a sense of that what was happening is not something that this town supports. And specifically, thinking about what would have happened in january of last year of 2017 when the travel ban happened, um, i think there were over 1,000 ppl that very quickly, within 48 hours, would have gathered, or 24 hours maybe, i can’t remember, but it was very quickly that ppl just kind of felt the need to gather. So its happening on campus, it’s happening to an extent also in this town and um, and then there are ppl that are more quietly just finding ways to support individuals um so they might not be as active in the public arena but they are very much wanting to help individuals that they know that are facing certain kinds of issues and helping to advocate for their health and well being.

Jake Adams: Well, I guess moving towards today, what is the, you mentioned that connecting w/ immigrants was a big part of the mission statemnet and thatremembeirng to build communities was abig thing to keep in mind. Um, what kind of, I guess, programs or goals is new bridges focusing on today? What kind of involvement is the org.?

Alicia Horst: So i think we’ve been fairly overwhelmed w/ questions that relate to immigration processes, so that’s certainly… our immigration protection progmation is certainly one of our top priorities. And you know how it is, when you have… it seems like sometimes there are clusters of things that happen at the same time for ppl that just create a lot of stress when you have, for example, an immigration process happen at the same time that you have a health like, stress, or whatever contributes to health needs, um, and they all kind of cluster together so… we have one person, for example, that almost exclusively is working on helping ppl to figure out how to pay off medical bills… cause those tend to skyrocket when ppl are stressed. So yeah uh those two ares. We also are connecting ppm to um classes and resources um for citizenship, for english, forum, jobs, for housing, there’s a lot of different things that ppl can access… it just that it feels like everybody’s priority right now is like “we’ll figure that stuff out later! Right now we’re sick and we’re stressed out about our status, those two things. Or how to maintain a status, b/c part of what’s been going on in the immigration environment right now that’s deeply disturbing is that for ppl that already have a status, they are placing more roadblocks in an already-complex system that used to exist, and so ppl that though they were ok are now facing something they didn’t expect. So that means that um, we are very focused on that, that kind of office work, and focusing less time on some of the things that would be like community groups and things like that, that certainly could be a tremendous amount of time could happen in that as well… and we have different kinds of groups that we are connected to where ppl from different walks of life, different languages get together… and there’s so much more that could be happening of that… how i wish we could do that (laughs) right now… yeah cause i mean i think it’s out of those relationships that we develop deeper empathy for one another no matter where we come from. Lots of us tend to have prejudices in different ways and so yeah.

Jake Adams: Uh, well… That was amazing. As a final question for you, is what you would like the public to know from your story? Um, i know that we spoke a lot about american culture and how that conversation is affecting groups of ppl that seem like they are not allowed to be part of the conversation… um, would would you like students to sort of understand from this predicament and your status as an immigration advocate?

Alicia Horst: I think one thing that has been important for me is that there are leaders that are telling their own stories, um, that dont need our permission to tell their stories. They’re already doing it and amplifying what they’re already doing is really really important. Um, it’s not important for me to tell somebody else’s story, it’s finding ways to support what they are already doing and i’m seeing what some of their priorities are or what next steps are. So i think what is important for me for the public to know is that in my mind, immigrants don’t need our permission to be here. It’s not something that we um.. I mean certainly there is a lot of work that needs to happen on the policy level but um there are lots of ppl that are already here already member of our society and so its more about us paying attention to what already is happening and less about trying to…….. For some reason we think its about us and it’s not in terms of…. We think that we are the ones that give people permission to stay here and to speak and all those things but it’s more about us realizing we are completely missing out when we um are not paying attention. Because i think um ppl that are already leading are leading in a way that actually ends up benefiting our society more in the end. Leading about what it means to live in community in a way that most ppl dont understand and… we talk about mental health in the united states as if its sorta like a medical condition this abstract form of what is actually going on in our society… and i think the leaders im talking about are persons that understand that mental health is connected to the fact that ppl are so isolated in our society. So what it means to have a cultural shift that creates a community where people in general not just new arrivals are healthy and well is something that we have so much to learn about. I know that this is a really broad concept but I think that immigrants can save us when it comes to that because they have a really important perspective on what it means to be to be healthy people in a way that a lot of people that grow up in the United States dont get. People are working themselves to death and they’re completely alone. It’s not a good mic and it’s gonna affect us long term in terms of what we see in violence and prejudice, it’s symptomatic of something else… in my mind. And this is not talking about the firearm debate and i;m not blaming that on mental health either, but yeah. (laughter)

Jake Adams: Well yeah thank you, that was… yeah thank you very much that was helpful and insightful. Are there any questions you would like to ask of me or anything else that you feel that you would want to discuss?

Alicia Horst: Hmm. No I think I’ve said plenty (laughter) yeah so i tend to think in big picture im not a very specific like “these are the policies that sure happen” so yeah you need to know that about me. I’m a more, broader conceptual individual.

Loading...

Loading...