President Duke’s completion of Wilson Hall in 1931 gave the James Madison University quad its centerpiece and brought his predecessor’s vision of bluestone symmetry one step closer to realization.The stately addition to campus provided administrative offices and an auditorium where commencements were held until Dr. Carrier moved them to the quad in 1971.

The building was named after President Woodrow Wilson, and his widow was among the prestigious guests who attended the building’s dedication. JMU (still The State Teachers College at the time) was a segregated school in the Jim-Crow South that was no doubt feeling the strain of the Great Depression, so it’s no surprise that they decided to honor a local (Wilson was born in nearby Staunton, Virginia) who was the first southern-born president to be elected since reconstruction. Though Wilson enacted sweeping domestic reforms under the “New Freedom” program that provided aid for farmers and offered support to students, he also had a hand in the passage of federal laws prohibiting interracial marriage and refused to endorse a constitutional amendment allowing women to vote. He was not shy about his prejudices, as evidenced by the glowing reviews he gave Birth of a Nation after enjoying a private screening of violently racist film in the White House.

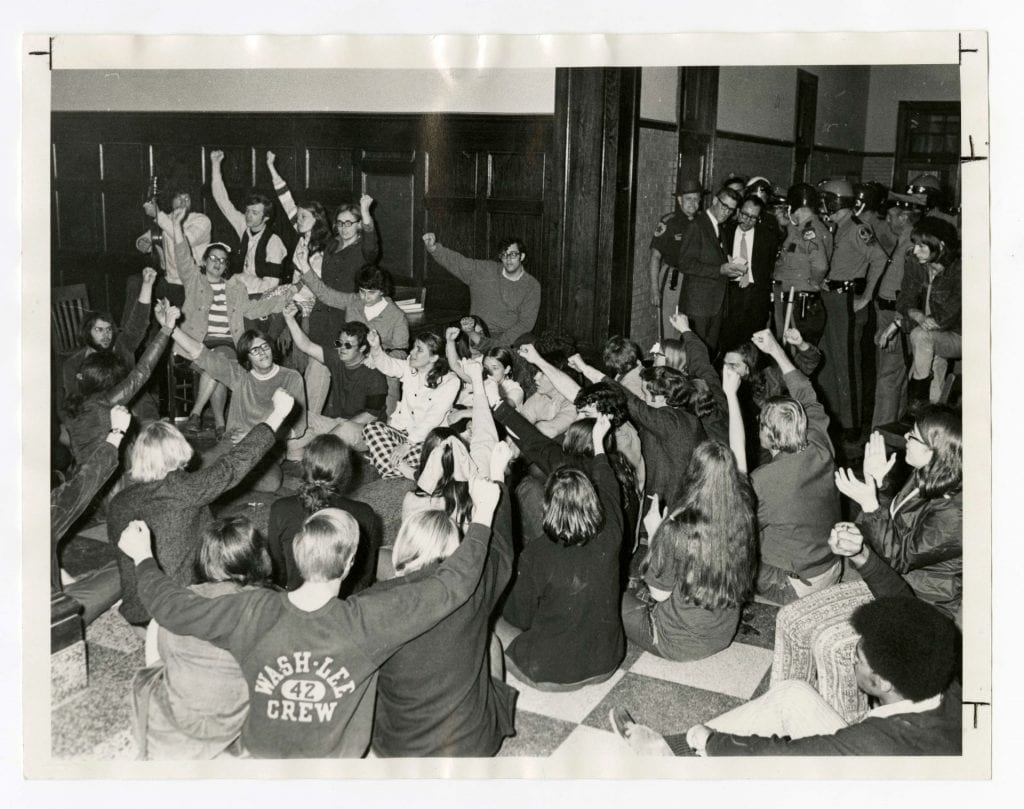

By 1970, the values reflected by the naming of Wilson Hall no longer represented those of the student body. That year, the foyer of Wilson Hall was the site of a sit-in, where students protested the “loss of academic freedom” after the unpopular decision to dismiss three faculty members. The event was organized by the notoriously radical student Jay Rainey, the first editor of JMU’s underground newspaper The Fixer, which was published from 1969 to 1973. The same year saw similar demonstrations at JMU opposing the war in Vietnam, part of a larger trend in colleges across the country.

Wilson Hall’s auditorium hosted a Miss America preliminary pageant in the early 1980’s. The Miss JMU Pageant was protested by faculty, whose petition ensured that the school’s esteemed scholarly reputation would never again be sullied by such a spectacle.

JMU saw a lot of presumably more acceptable spectacles in the 80’s as Dr. Carrier continued to transform campus culture. “Uncle Ron” brought in numerous big-name headliners, some of which (like Pat Benatar in 1981 and Rita Rudner in 1993) performed in the Wilson Auditorium.

Several prominent civil rights leaders have also graced the auditorium stage in Wilson Hall, including Coretta Scott King and Jesse Jackson. The number of inspiring figures invited to share their social progress messages with JMU students is small in comparison to the volume of popular entertainers, which indicates that the school’s priorities are on the right track, but could still use some work.

In 1994, a new generation of disgruntled students gathered at Wilson Hall to have their voices heard. This time, the issue at hand was the restructuring of the various schools within the university, with changes that included eliminating the Physics major. Dozens of protesters with picket signs marched in front of Wilson Hall, and the protest received national news coverage.

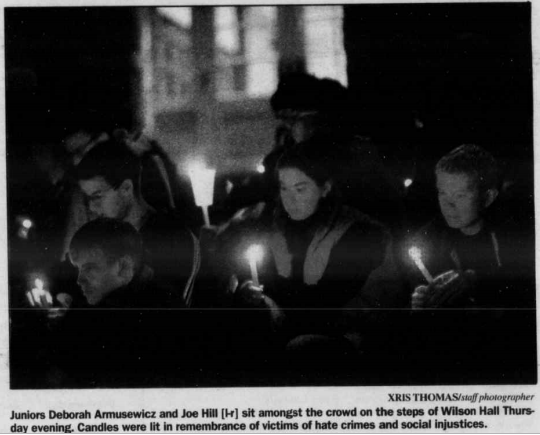

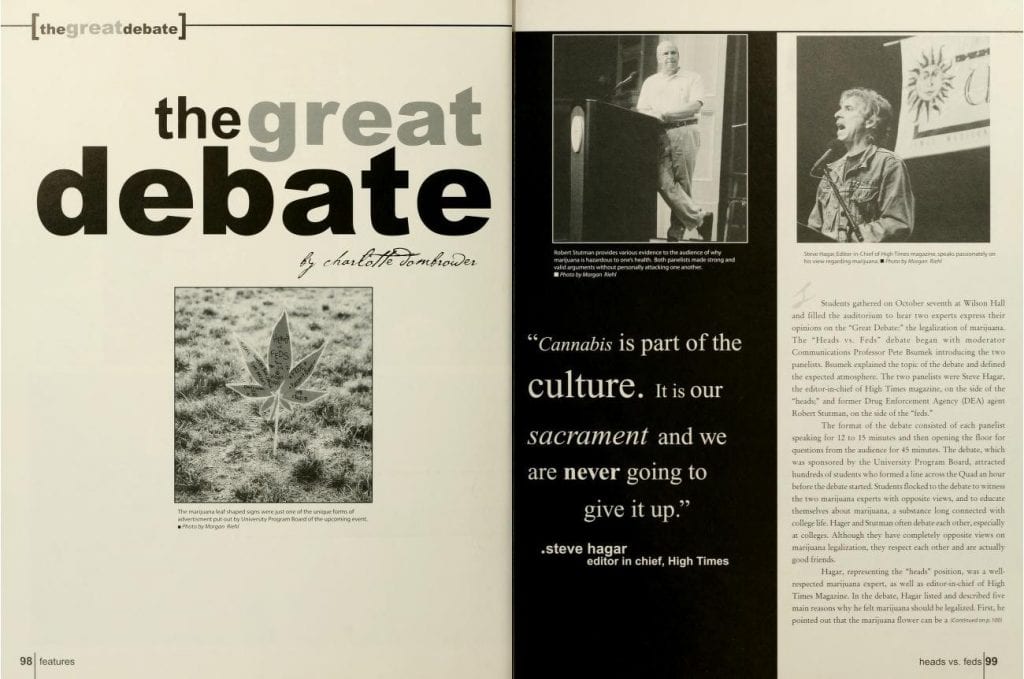

Students expressed their political views again five years later, when more than seventy people gathered on Wilson’s front steps for the “Stop the Hate” candlelight vigil organized by JMU Safe Zones and Harmony. The event aimed to spread awareness of “violence directed against people because of their racial, religious, ethnic, gender or sexual identity.” By the turn of the century, JMU’s student body had made it abundantly clear that they were willing and eager to take action about what was important to them, and that passion didn’t wane with the dawning of the new millenium. In 2002, hundreds of students and community members waited in a line that stretched the length of the quad to hear the editor-in-chief of High Times, Steve Hagar debate former DEA Agent Robert Stutman over the legalization of marijuana in Wilson’s auditorium.

Wilson Hall recently underwent its very first renovation. The $16 million project started in January of 2018 and transformed the administrative space into an academic one to better serve the needs of the steadily growing student body. Upon completion, the iconic building houses the entire history department, which hasn’t shared a single location in decades.

By Jessica Corsentino

Bonds, Jen and Richard Sakshaug, “Peaceful glow at Stop the Hate Vigil,” The Breeze, October 11, 1999.

Grantham, Dewey W. “The Era of Woodrow Wilson.” In The South in Modern America: A Region at Odds, 60-87. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5nph5k.8.

Hilton, Fred. “Myths and Legends- Ghosts and Violence.” James Madison University History Website. https://www.jmu.edu/about/history/myths_ghosts_and_violence.shtml

Hilton, Fred. “JMU Centennial Celebration – The First, Last and Only Miss JMU Pageant.” JMU Webstie. http://www.jmu.edu/centennialcelebration/miss_jmu.shtml (accessed February 5, 2019).

James Madison University. Bluestone,1981, 1983, and 2003. Harrisonburg, VA. JMU.

James Madison University. School Ma’am, 1933. Harrisonburg, VA. The State Teachers School.

Jay G. Rainey Papers, JMU Special Collections, Harrisonburg, Va.

Koch, Kamryn. “Wilson Hall to house history department after renovations.” The Breeze, September 20, 2018. https://www.breezejmu.org/news/wilson-hall-to-house-history-department-after-renovations/article_ccd2e174-bc63-11e8-99d2-bbf351785e15.html

Recent Comments