Influenza Virus and Vaccinations

Introduction

Influenza (Figure 1) is a highly contagious virus that is common in the United States and causes infection in humans. It causes mild to severe health complications including fever, nausea, body aches, fatigue, etc., and can sometimes lead to fatality (CDC, 2016). The viral infection commonly occurs every year, requiring an ever-changing flu vaccine to treat it because of evolving nature of the virus. Thus, the process it takes to create an effective vaccine is difficult and intensive, and poses a challenge to research scientists annually (Bar and Jelley, 2012). Mutations can cause a genetic drift in viral strains, which complicates the strain selection process, as illustrated by a Khan Academy YouTube video titled “Flu Shift and Drift”.

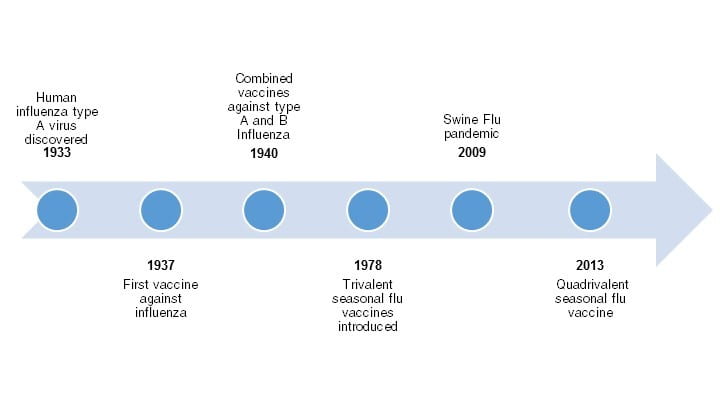

There are two main types of influenza, influenza A and B, that researchers must take into account when creating an effective vaccine. There is another influenza strain, influenza C, but is always present at low levels and is not used to create vaccines. Historically, the first influenza vaccine was monovalent (effective against influenza A), but has evolved along with the virus to become bivalent (influenza A and B), trivalent (two influenza A and one B), and now, quadrivalent (two influenza A and two B) due to new technologies (Hannoun, 2016; Figure 2). The World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for figuring out the types of strains affecting different regions of the globe, and which strains should be chosen to create an effective vaccine (Hannoun, 2016).

Figure 2. Timeline illustrating the development of the influenza flu vaccine. Created using Microsoft Word Smart Art; Source information from Bryan, 2014.

Viral Structure and Replication

Why is it so hard to distribute a vaccine properly in an influenza pandemic situation? The problem with vaccine distribution may not arise due to ethical choices, or flawed laws safeguarding certain populations as some may think. The real issue is outbreak preparedness and vaccine allocation. Vaccine allocation is crucial in pandemics, where there may not be enough vaccines for everyone. It is very difficult to be prepared for the influenza and other vaccines like it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Omi0IPkNpY

Influenza is a massively prevalent virus which makes it virtually impossible to eradicate for two main reasons; it mutates easily and has a large natural reservoir. Influenza not only infects humans, but birds, horses, and pigs. That gives the virus a large population to store itself and gather more mutations. The immune system works by being able to “remember” infections. However, influenza virus mutates rapidly because its genome is made of RNA and is separated into 8 fragments (When flu viruses attack! / Infectious Diseases / Khan Academy). The protein in charge of replication the genome, reverse transcriptase, is highly error prone and allows for many mutations. Another issue is that when two different strains of virus infect the same cell, there is no differentiation between the genomes and the resulting viruses could have a mixture of the two genomes.

Research and Development

Video 1: Descibes how vaccines work. Permission to use this video was given by its standard YouTube license.

Thus, changes to the vaccine inevitable result in the delay of resource distribution as a domino effect. This effect begins with the delay in research and testing to find a vaccine that effectively works for the new virus. Then it takes time to produce the vaccine on a scale for testing which requires surveillance. “Surveillance is essential for assessing vaccination coverage, informing programme planning, evaluating vaccine effectiveness, and monitoring safety in the population as a whole and in certain subgroups. Surveillance also allows the rapid detection of cases that may signal programme failure requiring remediation”(Moodley). After surveillance has taken place and the vaccine has been tested, it takes time to produce the vaccine on a larger scale for massive vaccinations for affected populations. After this production the distribution process is fairly simple, though there are some ethical barriers to be overcome.

The World Health Organization does the monitoring of influenza virus in conjunction with other labs around the world. They take the specimens from hundreds of countries in order to figure why type of influenza is affecting the country. The WHO takes all this information and decided which strains should be included in the vaccine in order to protect the most amount of people, whether it is a strain from a previous year or a new strain (Making flu vaccine each year / Infectious Disease /Khan Academy).

Manufacturing and Distribution Concerns Leading to Pandemics

Despite these previous concerns, one of the biggest problems with vaccines is the manufacturing. The demand for the vaccine usually peaks in October and declines after that, but the demand can be hard to determine and varies from year to year. Manufacturers say that, because of the unpredictable nature and complexity of biologics production, they cannot always anticipate when vaccine lots will be completed and released (2016 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Supply and Distribution in the United States). This manufacturing problem can cause delays, which can be troublesome if demands are high that year. As the world becomes more urbanized and person to person contact is increased, the flu will become easier to spread (The Threat of Pandemic Influenza 2012).

While time and funding place constraints on vaccine manufacturing, there is another dilemma with the required components in vaccine production. For example, hen eggs are traditionally used in manufacturing the influenza vaccine which are sometimes difficult to obtain in large quantities, especially if there is an epizootic outbreak in poultry. Cell-cultured virus vaccines provide an alternative to hen egg production. Recently cell-cultured viruses have become available but “the technical developments are not simple and currently, only a small proportion of the available influenza vaccines are produced in cell culture” (Hannon). Nevertheless, “The egg-based method is particularly problematic for bird-flu vaccines because the disease threatens chickens, which provide the essential raw material” (Pillar). Flu vaccine manufactures, then, have another concern when producing and distributing this life-saving resource.

The video below demonstrates the process of inoculating, incubating, harvesting, purifying, and splitting the influenza virus in hen eggs.

Video 2: Describes the process of using hen eggs to manufacture the influenza virus. Permission to use this video was given by its standard YouTube license.

There is always the threat of a pandemic, which occurs when a novel strain appears and spreads in the human population, which has little or no immunity. Most flu infections would not cause a pandemic, but if these viruses were to change in such a way that they were able to infect humans easily and spread, a flu pandemic could result. One of the important strategies governments will adapt is to make stockpiles of vaccines, which is just making more vaccines than they expect in case a pandemic occurs. When pandemics occur, there is so much chaos and confusion that allocating and making enough vaccines for everyone can be limited. It takes up to six months to make enough vaccines for a large population.

“The distributed nature of a pandemic, as well as the sheer burden of disease across the Nation over a period of months or longer, means that the Federal Government’s support to any particular State, Tribal Nation, or community will be limited… Local communities will have address the medical and non-medical effects of the pandemic with available resources (2006 Bush)”.

The flu pandemic in 1918 was the deadliest in history where 25% of the US population got sick (2016 Taubenberger). People died in a matter of hours or days from their first symptom, so having to wait 6 months for a vaccine would be catastrophic, not mention the fact that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for your body to make enough antibodies to work. More research needs to be done to increase the effectiveness of vaccines as well as increasing quantity to ensure public safety.

This past flu season outbreak was not handled well compared to past seasons (Wechsler). Vaccine efficiency was the highest in 2014, with a 51% effectiveness. Unfortunately, effectiveness has decreased in 2015, with a 23% effectiveness (2015 Pizzorno). Manufacturers struggled with vaccine production, leading to the delay of many shipments of the treatment. Some manufacturers, like GSK, had contaminated samples of the virus resulting in less effective vaccines (Wechsler). The procedure to develop vaccines is already elaborate, but it becomes more complicated considering how care and efficiency required of manufacturers.

In 1958, a new strain of the flu sparked a pandemic and vaccines were developed for it, but it was then rapidly replaced by a novel strain ten years later to begin work on (Hannoun). This requires a lot of time and money that some companies and organizations do not have, which then prolongs the distribution of enough vaccines. Manufacturers and researchers must continually monitor and develop treatments for these viruses which, in the case of the flu, they are usually not prepared enough.

New Technology to Improve Vaccine Implementation Delay

Video 3: Discusses the issues with vaccines today. Permission to use this video was given by its standard YouTube license.

Above, in his talk about HIV and flu; the vaccine strategy, Seth Berkley describes the issue with vaccines today. Berkley states that in order to be prepared for a pandemic situation we must be actively monitoring these viruses for change, the issue is that main companies moved away from this because it is bad business. Before some vaccines could be used, a new strain of virus was found. If we are to shorten the amount of time that it takes to research vaccines in a pandemic situation, we must actively monitor these viruses prior to the pandemic. Berkley also provides a solution to vaccine production. As of now, vaccine production is costly and a large facility is needed to do so. Berkley describes a form of production through the use of bacteria. This new technology would be inexpensive compared to current methods and would be easily transportable. Thus making vaccines easier to produce and cheaper overall. This initial shortening of the time gaps early on leads to a much faster distribution of the vaccine down the line, and would result in saving hundreds of thousands of lives.(DeScenza)

References

Barr, I. G., & Jelley, L. L. (2012). The Coming Era of Quadrivalent Human Influenza Vaccines. Drugs, 72(17), 2177-2185. doi:10.2165/11641110-000000000-00000. Berkley, S. (2010, February 20). Retrieved January 22, 2017, from https://www.ted.com/talks/seth_berkley_hiv_and_flu_the_vaccine_strategyutm_source=tedcomshare&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=tedspread (Links to an external site.) Bryan, J. (2014, May 15). It may not be perfect, but the influenza vaccine has saved many people's lives. Retrieved May 02, 2017, from http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/research/perspective-article/it-may-not-be-perfect-but-the-influenza-vaccine-has-saved-many-peoples-lives/11138389.article. Centers for Disease Control (2016). Key Facts About Influenza (Flu). Retrieved January 27, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/keyfacts.htm Making flu vaccine each year / Infectious Disease /Khan Academy. Retrieved January 21, 2017, from https://www.khanacademy.org/science/health-and-medicine/infectious-diseases/influenza/v/making-flu-vaccine-each-year Khan Academy [khanacademymedicine] (2013, Jan. 11) When flu viruses attack! [Video File] Retrieved January 21, 2017, from https://www.khanacademy.org/science/health-and-medicine/infectious-diseases/influenza/v/when-flu-viruses-attack?v=MNKXq7c3eQU Moodley, K. et al. (2013). Ethical Considerations for Vaccination Programmes in Acute Humanitarian Emergencies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91, 290-297. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/4/12-113480/en/ (Links to an external site.) Hannoun, C. (2013) "The evolving history of influenza viruses and influenza vaccines." Expert Review of Vaccines 12(9) 1085-094. Mclean, M. (2015). Allocation Resources -- A Wicked Problem. Health Progress, Nov-Dec;94(6) 60-67 [Nucleus Medical Media]. (2013, June 14). Influenza (Flu). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Omi0IPkNpY (Links to an external site.) Pillar, C. (2005, October 31) A Chicken-and-Egg Problem: How to Speed Up Production of Flu Shots. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-vaccine31oct31-story.html Preiss, S., Garçon, N., Cunningham, A. L., Strugnell, R., & Friedland, L. R. (2016). Vaccine provision: Delivering sustained & widespread use. Vaccine 34(52), 6665-6671. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.079 Roos, R. (2012, June 27). CDC estimate of global H1N1 pandemic deaths: 284,000. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2012/06/cdc-estimate-global-h1n1-pandemic-deaths-284000 [TED-Ed]. (2015, January 12). How do vaccines work? - Kelwalin Dhanasarnsombut. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rb7TVW77ZCs. Wechsler, J. (2015, March). Vaccine Development and Production Challenges Manufacturers. Retrieved from http://www.pharmtech.com/vaccine-development-and-production-challenges-manufacturers.

About the Authors:

John, Kayla, Naomi, Paige, Ryan, and Tyler are biotechnology students in the College of Integrated Science and Engineering at James Madison University. They are excited to have explored the science and technology issues associated with scarce resource allocation and outcomes in module 1 of their ISAT456 class on the ethical, legal, and social implications of biotechnology.

This was a collaborative class project that represents multiple viewpoints. Some views may not be shared by all contributors to this page.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Omi0IPkNpY