Scarce Resource Allocation

I. The 2009 H1N1 Swine Flu Outbreak

II. What We Learned From the H1N1 Outbreak

III. Pandemics Throughout History and How We Have Prepared

IV. How Are We Prepared Today?

This short video discusses the H1N1 flu outbreak and how it was spreading throughout the country in 2014.

The 2009 H1N1 Swine Flu Outbreak

The recent, 2009 H1N1 flu outbreak caused an uproar in our society, affecting thousands of people worldwide. This outbreak first emerged in Mexico and was discovered in the U. S. in April 2009. The horrible widespread effect of the disease caused President Obama to declare a national emergency. School closings, hospital surges, and the uncertainty of the disease were among the challenges we faced. The unexpected pandemic put our preparedness to the test.

What we learned from the H1N1 outbreak

An ounce of prevention is a pound of cure. Being prepared at a moment’s notice is the best way to combat a Pandemic. This means being able to handle a surge, ensuring that uninsured and underinsured civilians are protected, and the line of communication remains strong between administration and the public. Communicating on a local and global scale is a key component is minimizing fear and confusion across the affected areas. The use of vaccine is instrumental in preparedness for a pandemic. Making sure the maximum amount of Americans are vaccinated, with the most up to date vaccine, and stockpiling the remaining medication, ensures a plan to protect Americans. The ripple effect was badly seen from the H1N1 outbreak, when schools, offices, and community resources were closed down. It’s important to understand the trade off between public health safety, and keeping a functioning society, and we learned that it is a very fragile line.

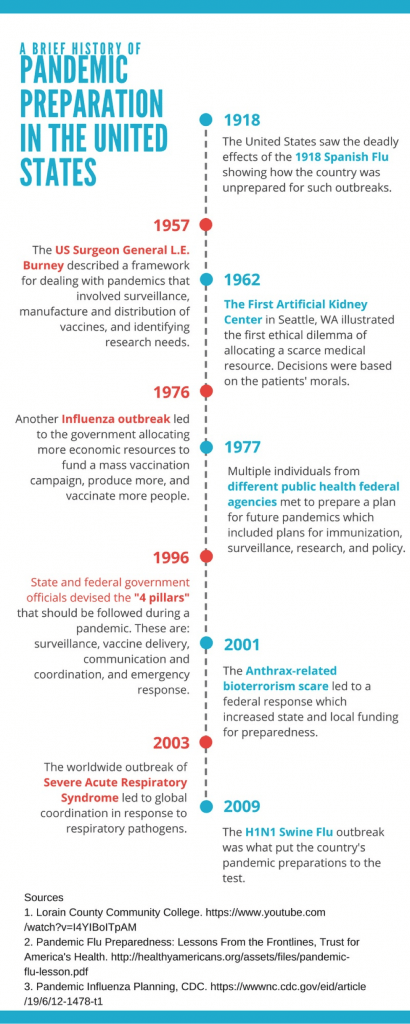

Pandemics Throughout History And How We Have Prepared

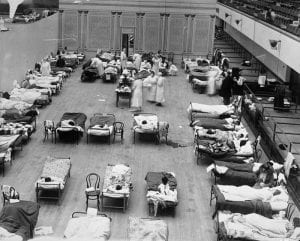

This image is of a temporary treatment center opened at the Oakland Municipal Auditorium during the 1918 Spanish flu (Rogers 1918).

Our human history has been riddled with epidemics, with records dating back to as early as 430 B.C. with a smallpox outbreak reducing the population of Athens, Greece by at least 20%. Outbreaks continue through history, with the Plague of Justinian beginning in 531 and lasting on and off for nearly 200 years, with the Great Plague of London actually beginning in China in 1334, with smallpox popping up in Mexico, Massachusetts, and Boston in 1519, 1633 and 1901 respectively, with the Modern Plague attacking China and India in 1860, and with the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. All of these outbreaks decimated populations, killing in numbers of 2-50 million (CNN, n.d.).

Coming to the U.S., we did not have any standard framework for how the U.S. would respond to an epidemic until 1978. In 1960, the surgeon general outlined a plan to respond to a new epidemic, but this was generally ignored for the next 18 years until the first U.S. pandemic response plan was officially written and adopted. This has been revised numerous times since (Iskander et al. 2013), yet as displayed in the H1N1 outbreak, things still are not completely satisfactory.

Along with an ethical plan for distributing resources, we of course need access to these resources that will be distributed. In the event of a disease epidemic, a seemingly endless variety of medical supplies, equipment, vaccines, antibiotics, and countless other products that are imperative to people’s survival are necessary at a moment’s notice. To prepare for this, a national stockpile was created. Started in 1983, the stockpile was originally intended to be a backup up to hold a six-month supply of all recommended childhood vaccines in case there were interruptions in manufacturing (Lane et al. 2006). Jump forward to today and our stockpile is much more fully prepared with antibiotics, chemical antidotes, antitoxins, many more vaccines, antiviral drugs, personal protective equipment, ventilators. The stockpile also has an association with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to develop new medical countermeasures that could be necessary in a variety of situations (“Stockpile Products,” 2016).

Along with an ethical plan for distributing resources, we of course need access to these resources that will be distributed. In the event of a disease epidemic, a seemingly endless variety of medical supplies, equipment, vaccines, antibiotics, and countless other products that are imperative to people’s survival are necessary at a moment’s notice. To prepare for this, a national stockpile was created. Started in 1983, the stockpile was originally intended to be a backup up to hold a six-month supply of all recommended childhood vaccines in case there were interruptions in manufacturing (Lane et al. 2006). Jump forward to today and our stockpile is much more fully prepared with antibiotics, chemical antidotes, antitoxins, many more vaccines, antiviral drugs, personal protective equipment, ventilators. The stockpile also has an association with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to develop new medical countermeasures that could be necessary in a variety of situations (“Stockpile Products,” 2016).

How Prepared Are We Today?

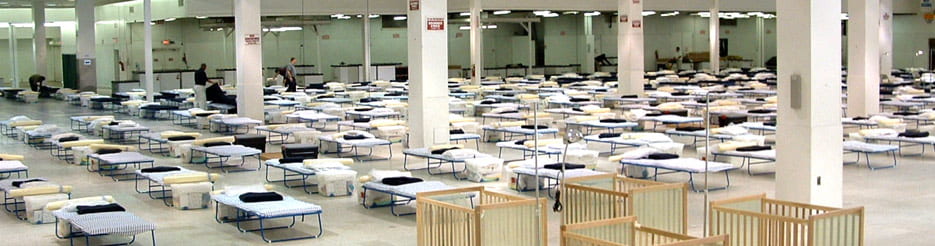

A modern temporary treatment center, looking essentially the same as the image previously shown from 1918.

Although it appears that the United States has enhanced its preparation for an epidemic, there is still a great deal of improvement to be made, especially in terms of the economy. The 2015-2016 outbreak of the Zika virus is a prime example of how our economy was unable to fully support an epidemic. Though there were few cases, those that were infected tended to have a difficulty receiving the proper treatment with ease. Pregnant women that had been in an infected area were highly encouraged to undergo more frequent and thorough examinations for the child. If the child was deemed infected, the woman was to seek a specialized doctor capable of handling a complicated and pre-term delivery. In this case there needed to be more intervention on the government’s part to ensure that these cases were handled properly and there were resources for those potentially and confirmed at risk (CBS. 2016). Even with minimal cases of Zika in the United States, especially amongst pregnant women, there was a major lack of access to the proper care and expertise to care for both the woman infected and potentially the child.

The United States preparations were also put to the test during the recent 2009 H1N1 Swine flu outbreak. As the outbreak occurred strengths in the country’s pandemic preparation were seen as communication was mostly effective between certain parties. The president and other spokespeople were able to effectively spread information such as proper hygiene techniques and the fact that certain myths about the outbreak were false (Levi et al., 2009). Antiviral stockpiles and greater vaccine manufacturing capabilities were also key in combating the outbreak, even though some health departments still lacked the optimal amount of resources needed (Levi et al., 2009). While the country did excel in some areas when handling the outbreak, weaknesses were also seen as it was hard to keep sick people from going to work, among other issues, especially in the private sector where sick leave is limited (Levi et al., 2009).

About the Authors

Brooke, Colin, Rachel, Sabrina, Shaw, and Tryphena are studying the historical context and economic issues within scarce resource allocation. Together they make up the Bioethics Group in their ISAT 456 course, Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Biotechnology, in one of the largest schools in Virginia, James Madison University.

Disclaimer: This was a collaborative class project that represents multiple viewpoints. Some views may not be shared by all contributors to this page

Sources:

CDC director on protecting women against Zika virus [Television broadcast]. (2016, June 2). In This Morning. Atlanta, Georgia: CBS.

“Deadly Diseases: Epidemics throughout History.” CNN. Cable News Network, n.d. Web. 31 Jan. 2017.

Iskander, J., Strikas, R. A., Gensheimer, K. F., Cox, N. J., & Redd, S. C. (2013). Pandemic Influenza Planning, United States, 1978–2008. Emerging Infectious Diseases,19(6), 879-885. doi:10.3201/eid1906.121478

Rogers, E.A. (1918). American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards setup inside Oakland Municipal Auditorium, 1918 [Online Image]. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/1918_flu_pandemic#/media/File:1918_flu_in_Oakland.jpg.

Stockpile Products. (2016). Retrieved January 31, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/phpr/stockpile/products.htm

Levi, J., PhD., Inglesby, T. V., MD, Segal, L. M., MA, Vinter, S., MHS, Courtney, B., JD, MPH, Elliott, K., MA, . . . Kadler, R., MD. (June 2009). Pandemic Flu Preparedness: LESSONS FROM THE FRONTLINES. Trust for America’s Health.

Infographic obtained from http://www.takepart.com/sites/default/files/contagion/index.html#&slider1=1. Permission was granted for reuse of image on 2/1/17.