Scarce Resource Allocation

I. Utilitarianism and Global Prioritization

- Social worth

- Cost effectiveness

- Productivity of society

- Maintaining societal order

II. Prioritization by Social Worth on a National Level

- First responding groups: Firemen, policemen, paramedics, doctors and nurses, medical researchers

- Preserve functionality of most important cities

- Extend aid outward from most important cities

III. Patient-level Prioritization

- Equitable treatment of all

- Preserving dignity of patients

- Maintaining freedom of choice

IV. Who’s in Charge?

- The leading nations that remain? The UN? Situation dependent

I. Global-level Prioritization

At the most severe end of the disaster spectrum the guiding principles are inherently different from the guiding principles on a normal day at the hospital. Global pandemics, cataclysmic natural disasters, large-scale terrorist attacks, and disasters of similar magnitude require a huge expansion of scope. The consequences of such an event are so serious that many things that are normally important no longer matter. The first priority must always be the survival of humans as a species. The second must be maintaining order and the productivity of the communities that remain.

In treating everyone fairly, the result is fewer lives saved and more suffering for everyone in need. If a lottery system were to be used and everyone that won the lottery was old and frail then those resources did not do the most good they could have. Directing those resources towards doctors and nurses could mean many more patients treated. Directing those resources towards first responders could mean many more victims rescued. Directing those resources towards vaccine workers could mean countless life-saving inoculations distributed. The consequences of not directing resources towards these sort of individuals must be factored into the cost-effectiveness analysis (Brock & Wikler, 2006). When an individual who can contribute to the aid of others is saved, the benefits are two-fold. By prioritizing those that are most useful to the whole community, the most good is done.

Choosing to sacrifice one to save many is a hard decision to make but, all things being equal, the most good is done when you make the right decision.

II. Prioritization by Social Worth on a National Level

As we move from the most catastrophic scenarios imaginable to less severe ones the priorities begin to move away from utilitarianism and back towards the equitable treatment of all. When the lives of all humans and the fabric of a global society are no longer at risk we can begin to make decisions that will benefit the most people, not just the most important people. Prioritizing first responders like firemen, policemen, paramedics, doctors, nurses, medical researchers, etc. allows the scarce resources that we use to have benefits that are two-fold. These groups of people can contribute to solving the problems following a disaster of nationwide scale. By focusing our efforts on population centers we help the most people by avoiding wasting resources on travel and preventing the spread of disease among individuals within close proximity to one another. As the problems among the largest groups are solved then we can begin to direct resources towards the surrounding areas. Social worth can be defined in many ways, it can include age, seniority, rank, expertise and sometimes wealth. This method of allocation takes a practical perspective, favoring people who are able to contribute back to the greater good (Seebauer, 2017).

III. Hospital-level Prioritization

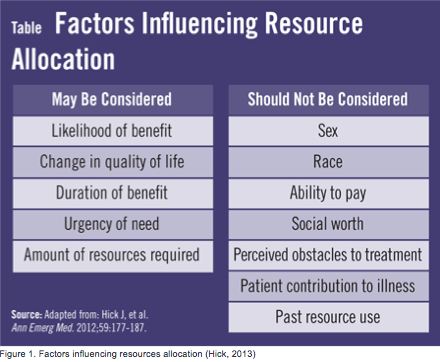

Methods for allocation of scarce medical resources in a hospital was developed by the American Medical Association for organ shortage (Hick et. al., 2013). Figure 1 shows factors influencing resource allocation on an everyday basis, this method can be altered in urgency for resource decision-making in the event of an emergency. In a situation like this, every patient that walks into the hospital is likely to be considered an “urgent” case.

“In certain situations minimum qualifications for survival may have to be defined, beyond which further resource commitments to that patient are unlikely to result in a good outcome and will consume disproportionate shares of a scarce resource.” (Strosberg, 2008)

There is also an importance in letting the public know about the method of resource allocation being implemented, otherwise, they are unlikely to comply and cooperate. Distribution of scarce resources can occur in three main ways:

- Treating people equally:

- First come, first served

- Utilitarian:

- Prioritizing where the resources will be most effective to do the most good for the most people

- Favoring the worst-off:

- Focusing resources to the ones in greatest need. In a medical triage, the goal is to do the most good for the most people and to grant resources to the greatest in need

When making allocation decisions, one can either look at medical factors or social factors. In a hospital or triage setting, it is almost impossible to judge a person’s social worth bedside. Social worth evaluations are subjective and can take time therefore, doctors, nurses, and first responders focus resource allocation based on medical factors.

An example of a current scarce resource and its allocation was brought to the public’s attention via an article written by Steve Johnson that appeared in the “Times Free Press”. He wrote an article on a man who was in desperate need of a heart and kidney transplant at the age of 71 and according to policy of that hospital “patients over 70 years of age were not eligible for heart transplants because surgeons believed it was unlikely they would survive the operation” (Johnson, 2016). He eventually fought hard enough and got both the heart and kidney transplant.

III. Who’s in Charge (Decision Making)

“What is a death panel? Is it fair to have a socialized healthcare system where an accountant decides whether your grandma lives or not?” (Mecham, 2016)

Listen to Scott Mecham give a informative speech on what really is a death panel, and how people become in charge of major ethical decisions about scare medical resources and there allocation.

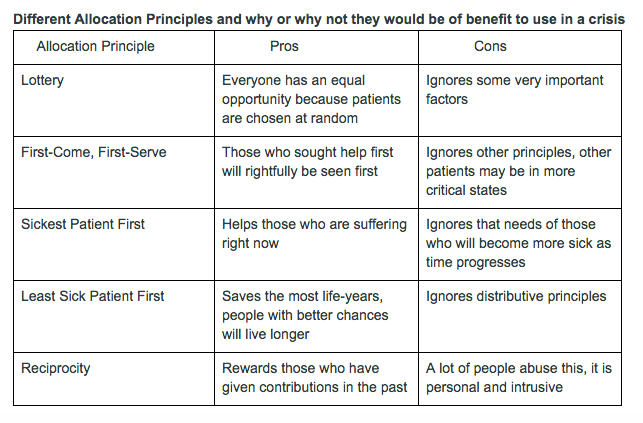

On the city scale a broad spectrum of health care providers and emergency physicians are the ones who have the hands-on decision making in the allocation process of scarce resources. The health care providers take into consideration the type of scarce resource to conceive a method to employ when choosing who gets the scare resource from a single principles or a combination of multiple principles of allocation; some of the most popular principles are listed in Table 1.

On the national level, the US Department of Health & Human Services provides a Crisis Standard of Care stating how to make ethical decisions when allocating scarce resources. A lot of the national decision methods rely on saving the most lives and making the best possible health outcomes as a whole. The Crisis Standard of Care employs ethical values for health care providers across the nation to follow to ensure fairness and justice in the allocation process. Additionally, organizations such as the National Vaccine Advisory Committee and Food and Drug Administration also have their ethical standards of care during crises.In conclusion, there is more than one decision maker on the national level: a board of people in the Department of Health and Human Services decide on principles and their ethicality in specific situations for health care providers to go by when allocating scarce medical resources. Each state has laws in place for who gets put on a waiting list for the scarce resource and where on that list a person may be, every allocation method will vary among states and hospitals. Allocation of scarce resources is entirely situational; meaning the decision you make is completely dependent on what the crisis is and what would work best in the situation. Even in European countries, when it comes down to the nitty-gritty of who will acquire the resource, it depends on which country you are in and which standards to go by directly fit your situation.

This was a collaborative class project that represents multiple viewpoints. Some views may not be shared by all contributors to this page.

Works Cited

(2016, June 02). What is a Death Panel? Retrieved January 31, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4wYGNziJhs

Brock, D. W., & Wikler, D. (2006). Health Resource Allocation In Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (Chapter 14). Retrieved from NCBI Bookshelf

Copyright © 2017 National Academy of Sciences. All Rights Reserved. (2015, August 19). Retrieved January 31, 2017, from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2012/Crisis-Standards-of-Care-A-Systems-Framework-for-Catastrophic-Disaster-Response/Report-Brief.aspx

Daugherty Biddison, E. L., Gwon, H., Schoch-Spana, M., Cavalier, R., White, D. B., Dawson, T., … Toner, E. S. (2014). The Community Speaks: Understanding Ethical Values in Allocation of Scarce Lifesaving Resources during Disasters. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 11(5), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-379OC

Emanuel, E., & Wertheimer, A. (2006). Who Should Get Influenza Vaccine When Not All Can? Science, 312(5775). Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Hick, J. L. M. (2013). Planning for a Resource Shortfall | Physician’s Weekly for Medical News, Journals & Articles. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://www.physiciansweekly.com/emergency-resource-shortfall/

Krütli P, Rosemann T, Törnblom KY, Slmieszek T (2016) How to Fairly Allocate Scarce Medical Resources: Ethical Argumentation under Scrutiny by Health Professionals and Lay People. PLoS ONE 11(7): e0159086. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159086

Liss, P. (2006). Allocation of scarce resources in health care: values and concepts. Texto & Contexto – Enfermagem, 15, 125-134. doi:10.1590/S0104-07072006000500014

Martin A. Strosberg, PhD, M. (2008). Allocating Scarce Resources in a Pandemic: Ethical and Public Policy Dimensions. AMA Journal of Ethics, 8(4), 241–244.

Priorities and Resource Allocation in Health Care. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2017, https://www.iwe.uni-bonn.de/research-projects/priorities-and-resource-allocation-in-health-care

Persad, G., Wertheimer, A., & Emanuel, E. J. (2009). Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. The Lancet, 373(9661), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9

Rogowski , W., Grosse, S., Schmidtke, J., & Marckmann, G. (2014). Criteria for fairly allocating scarce health-care resources to genetic tests: which matter most? European journal of human genetics , 22(1), 25-31. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Seebauer, E. G. (n.d.). Types of Resource Allocation. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved January 28, 2017, from http://www.scs.illinois.edu/~eseebauer/ethics/Advanced/Allocation.html

Noelle Luis, Amanda-Leigh Pyle, Emily Smith, Marissa St. George, & Cole Warren