Genomics, Rights, and Justice: The Belmont Report

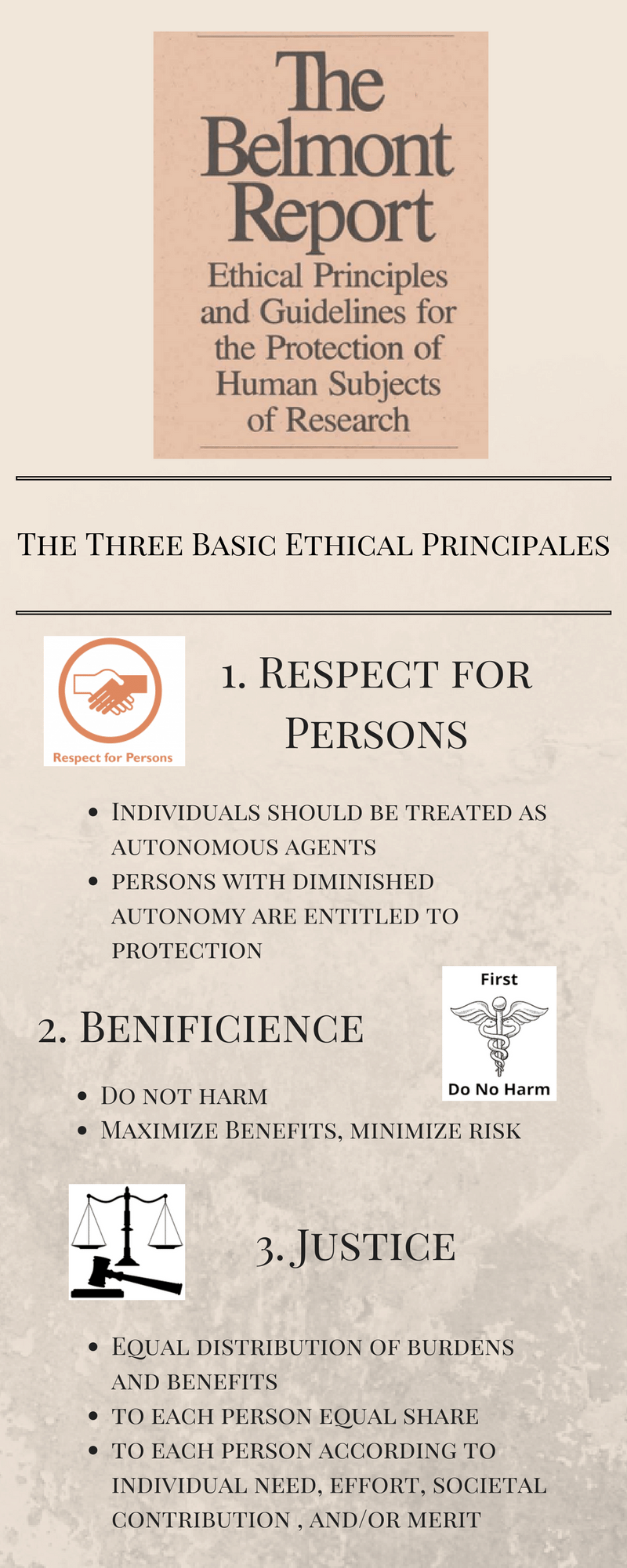

Figure 1. Info-graphic, made using Piktochart, illustrating the three basic principles outlined in the Belmont Report, as well as the components that make up each principle.

The Belmont Report, issued on September 30th, 1978, was created in order to prevent the unethical treatment of human subjects in scientific experiments. It was written by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Services of Biomedical and Behavioral Research following the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1978) due to the unfair and unjust actions conducted by U.S. Public Health Service on African American men whose state of diminished autonomy during the time was taken advantage of to promote the research on syphilis. The authors of the report intended to promote greater supervision over scientific experimentation on human subjects and delineate clear guidelines on how human subjects should be treated. There are three central themes that the National Commission outlined in the report in order to guide researchers in the direction towards ethical experimentation. These are termed the “Three Basic Ethical Principles” that centralize on maintaining respect for persons, beneficence, and justice for all humans experimented on, regardless of societal status.

In Genetic research among the Havasupai: A cautionary tale, Dr. Levine was one of the coauthors of the Belmont Report and in the clip he goes into some background information, including the reasons it was created as well as some key cases along the way (Sterling 2011).

Respect for Persons & The Tuskegee Study

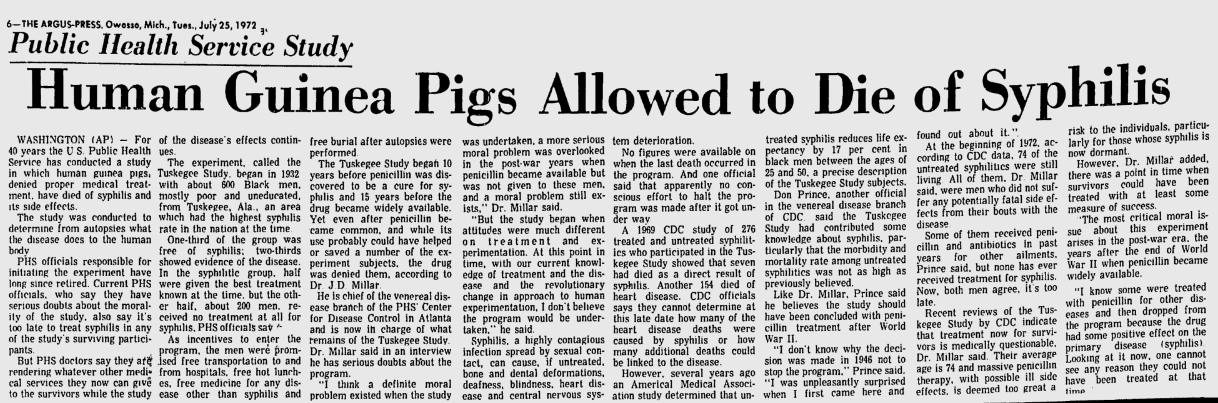

The first principle in the Belmont Report, respect for persons, establishes that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents free to make their own judgments and decisions. Beyond this, individuals with diminished autonomy should be given special protections. As researchers we must respect all persons in our studies regardless of their age, physical health, mental status, social status, economic status, education, culture, and race. In one specific case study preceding the Belmont Report respect for persons was violated. The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” began in 1932 and continued until 1972. 600 black men, 399 with syphilis and 201 without, were researched for the effects of syphilis; however, they thought they were receiving treatment for “bad blood”. In the Tuskegee syphilis study, respect for persons was denied as the subjects were lied to, did not give their informed consent to participate, and were not given the option of receiving effective treatment when it became available. Respect for persons requires that research participants are given thorough and truthful information to aid them in decision making but the Tuskegee subjects had limited and manipulated information at best. Even so, no special protections were made for the subjects. In the 1930’s-1970’s black men in American society had seriously diminished autonomy based on race and found themselves in “circumstances that severely restrict liberty” (Belmont). Furthermore, most of the men in the Tuskegee study came from homes in poverty and were not formally educated. The image below illustrates how the Tuskegee subjects were not respected as equal beings.

Figure 2. Public Health Service Study—Human Guinea Pigs Allowed to Die of Syphilis. (1972, July 25). A newspaper article published at the end of the study refers to the research subjects as “human guinea pigs” illustrating the way in which these men had their autonomy revoked and were unable to make their own decisions about participation.

When penicillin became an accepted, available treatment for syphilis in 1945, researchers did not offer it to their subjects. Instead, researchers continued their studies of the untreated syphilis. The Belmont Report established that “The judgment that any individual lacks autonomy should be periodically reevaluated and will vary in different situations”. With penicillin available to intervene in the natural course of untreated syphilis, the situation in Tuskegee had greatly changed. Researchers’ decision to continue certainly violated respect for persons.

Beneficence & Henrietta Lacks

The second principle outlined in the Belmont Report explains that harm should not come to human research subjects, and that as many benefits as possible be obtained from that research. Henrietta Lacks was an African American woman diagnosed with cervical cancer as a result of Human Papillomavirus (Skloot). Upon inspection of her condition, a doctor named George Gey extracted some of her cancerous tissue as a sample to study without her knowledge and consent (Skloot). He discovered that her cells would continually replicate themselves, so even when some of the cells died out there were plenty to take their place. The newly named HeLa cells were distributed to labs all over the world and used for research (Harmon). These unlimited reservoirs of cell cultures led to many important discoveries that were made in the field of molecular biology such as the development of the polio vaccination (Skloot). In this, the Belmont Report agrees research should help as many as possible concerning issues like these. However, it also wanders over to the area concerning the ethics of the research, such as how the Lacks family did not receive any sort of compensation for all the benefits that came from their mother’s cells. Because of this, we can still ask “who exactly should benefit from this research?” Should research in this field only be validated if it benefits a certain group of individuals? Considering these inquiries, one can understand that the Belmont Report does not fully address these modern issues either.

Video 1. Video displaying a brief overview of Henrietta Lacks’ role in the use of HeLa cells, how HeLa cells work, and how they have been used throughout history to fuel the progression of science.

Justice & The Havasupai Case

The Belmont Report refers to Justice in terms of “fairness in distribution”. One such case where vague informed consent leads to injustice is that of the Havasupai Tribe. In “Your DNA Is Our History Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property” Jenny Reardon and Kim TallBear explore the ways in which indigenous populations have been exploited in scientific research (2012). An argument presented is that if indigenous populations represent modern humans at an earlier point in evolution then indigenous DNA is inherited to modern humans as property. In 1990, although researchers from Arizona State University gained consent to use DNA from the Havasupai Tribe to “study the causes of behavioral/medical disorders” many tribe members believed their blood samples would only be used in research about diabetes. When studies about migration patterns on the Havasupai DNA surfaced, many subjects felt deceived. With this type of exploitation, distrust may arise between the indigenous people and the researches. As a result of this distrust, indigenous people do not receive the same benefits that those of European descent do. This distrust leads to an uneven distribution of benefits, and is a direct violation of the justice principle of the Belmont Report.

Video 2. Above Keolu Fox describes how historical distrust between European research and indigenous people will hurt indigenous people in terms of medical development.

The Belmont report:

Figure 3. Info-graphic, made using Canva, depicting a historical overview of major incidences and cases regarding tissue ownership and the issues behind it. Also shows the progression of how policies concerning tissue ownership have changed around the world.Conclusion: The Belmont Report in the 21st Century

- Is a statement of ethical principles, not rules for human testing.

- Before this report, unethical research was being performed on people, often on vulnerable populations.

- Its broadness is its strength but it’s also its weakness (Levine, 2011).

- While ethical principles are very important, this document needs to be updated due to vagueness in word choice, contradictions, and the changing times.

Scientific advancements after the Belmont Report:

Examples where it has been found that the Belmont report is lacking:

- Henrietta Lacks

- The Havasupai

- Court cases like Moore vs Regents of the University of California

- The rights to and ownership of tissues and DNA have not been firmly established (it was hard to determine who a cell line belongs to)

- DNA could not yet be sequenced until 1977 so this was not a was not a problem when the Belmont report was written

- A DNA sample can be sequenced in as little as 7 hours to 6 days.

Justice in the Belmont Report:

- These advancements in technology created a new issue of usage and ownership as seen in the cases of Henrietta Lacks, Moore, and Havasupai people.

- The DNA was taken from members of the Havasupai with informed consent for the intent of researching diabetes. For more information on this case, see Legal page.

- The ideals of the Belmont report were not breached and it did not break any laws of human treatment or usage.

- According to the Belmont report, should there be justice for the people that these cell samples came from, and who owns them?

Vagueness and Respect for Persons in the Belmont Report:

- can be interpreted in many ways which leads to confusion.

- the authors use the phrase “to give weight”, but this does not mention how much weight to give.

- One of the vaguest passages in the report was the respect for persons. One of the most common problems with conducting health research is the subject is overly optimistic and even misinformed about the value of their own cases. If someone believes a certain medication would treat their ailment even when the researcher has told them it is unlikely to help, does the researcher continue to explain that this treatment most likely will not work? (Miller, 2003).

- Every opinion should not be weighed the same. The Belmont Report states that “… to show a lack of respect for an autonomous agent is to repudiate that people considered judgments, to deny an individual the freedom to act on those judgments”. This can be wrong because if the government wants to make vaccines mandatory for everyone and some people believe vaccines are bad, should the researcher take this opinion into account even though it is wrong? (Miller, 2003).

- Respect for persons needs better language

- In the Havasupai case, scientists believed they were following guidelines by obtaining their written consent, but they should have ensured the tribe knew what was going on they should have gotten additional consent forms for the other research (sterling, 2011).

- The Belmont report does not tell us we need consent for every use for that blood, and if that system was in place it would cause a bureaucratic overload and nothing would get done.

- The general understanding is once something is out of your body, it is no longer yours.

Video 3. The Belmont Report and New Challenges in Research gives some critiques on the Belmont report. She says that it might not give scientists enough freedom to be creative and we need as little restrictions as possible to make sure science is done in an ethical (Lee 2014).

Most scientists argue that the Belmont Report was not written in stone and should change as society changes. However, by creating more and more rules, it limits scientist’s creativity so we need as little restrictions as possible to ensure science is done in an ethical manner, depicted in the video above. This can be challenging because you want to allow scientist certain freedoms, but you don’t want to allow for holes to allow scientists to conduct unethical research. As technologies continue to advance and change, we may need to alter them, especially involving the speed that the information is available. The founders of the documents did not know all the uses of someone’s blood (Lee 2014). Although the Belmont report is vital in regulating ethics, it should be updated and we need to acknowledge that it has limitations and should be used in a broad manner.

Works Cited

Fox, K. (2016, February). Retrieved February 20, 2017, from https://www.ted.com/talks/keolu_fox_why_genetic_research_must_be_more_diverse#t-396781

Public Health Service Study—Human Guinea Pigs Allowed to Die of Syphilis. (1972, July 25)

Retrieved from https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1988&dat=19720725&id=Zw4oAAAAIBAJ&sjid=8gQGAAAAIBAJ&pg=690,2312863&hl=en

The Belmont Report. (April 1979) Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont Report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. National Institutes of Health. http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/guidelines/belmont.html. Accessed January 22, 2017.

The Tuskegee Tinmeline. CDC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

Levine, R. J. (2011, August 16). Research Ethics [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jD-YCDE_5yw

Miller, Richard B. (2003) "How the Belmont Report Fails," Essays in Philosophy: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 6.

Ngo, R. (2017, February 22) The History of Tissue Ownership. Retrieved from https://www.canva.com/design/DACN7ci80ZM/ZWRAFGB_izl45Se_QOL2jg/view?website

Skene, L. (2002). Ownership of human tissue and the law. Nature Reviews Genetics,3(2), 145-148. doi:10.1038/nrg725

Wagner, J. K. (2014, June 11). Property Rights and the Human Body. Retrieved February 20, 2017, from http://www.genomicslawreport.com/index.php/2014/06/11/property-rights-and-the-human-body/

Schleiter, K. E. (2009). Donors Retain No Rights to Donated Tissue. Virtual Mentor,11(8), 621-625. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.8.hlaw1-0908

Sterling, R. (2011). Genetic research among the Havasupai: A cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor, 13(2), 113–117. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.2.hlaw1-1102 https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=5&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwi0vNmTgZ_SAhULxVQKHVeYD-YQFgg1MAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fbioethics.as.nyu.edu%2Fdocs%2FIO%2F30171%2FSteinberg.HumanResearch.pdf&usg=AFQjCNEANz7ICCjG9v7u7gN6lGx4-u6lUQ&sig2=H_i4pfaGy31WSlUuQfiKVg

Harmon, A. (2010, April 21). Indian Tribe Wins Fight to Limit Research of Its DNA. The New York Times, pp. 1–5

Reardon, J., & Tallbear, K. (2012). “Your DNA Is Our History”. Current Anthropology,53(S5), 233-245. doi:10.1086/662629

About the Authors

Naomi, Kayla, Ryan, Tyler, John, and Paige are ISAT456: Ethical, Legal, and Societal Implications of Biotechnology students at James Madison University. They have been analyzing genomics, justice, and rights from historical and economic perspectives in this module.

This was a collaborative class project that represents multiple viewpoints. Some views may not be shared by all contributors to this page.