A National Phenomenon: The Superhero Comic Revolution

by Julian Chambliss

“Superman may have arrived from a distant planet, but his real origins lay in Cleveland, Ohio.”[1]

As this quote from Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture suggests, for comic scholars, questions about space shape any consideration of superhero comics’ meaning and impact in the United States. Yet, this relationship is often framed in the abstract as comic scholars see the superhero as an expression of modernism, cataloging changes to society and offering reassuring symbolic narratives to a population trying to cope.[2] In this formula, Superman’s Metropolis and Batman’s Gotham captured the modern city’s potential to offer benefits and cause harm.

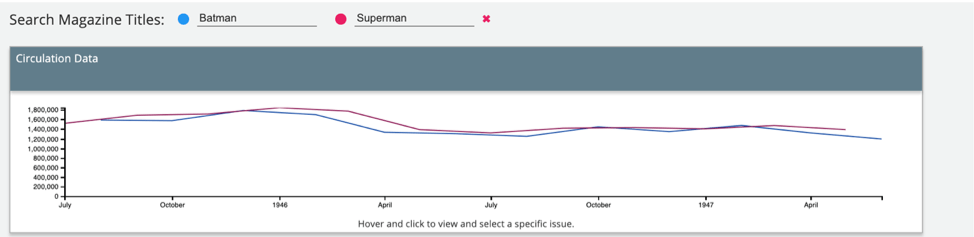

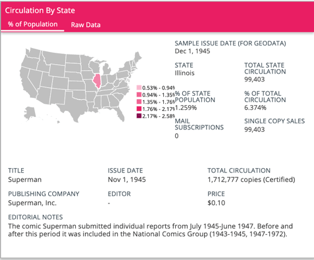

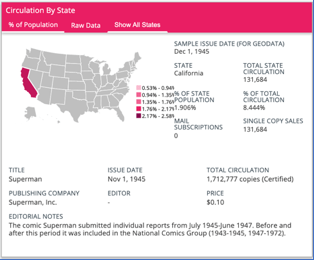

Information from The Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) offers us an opportunity to measure the relationship between readership, superhero, and space. Does the “urban anxiety” so central to American experience mean Superman is more popular in rural areas?[3] Does the vigilante justice, crouched in coded class and racial ideas, mean Batman appeals to urban readers? The numbers make clear readers engaged with Superman and Batman in a similar manner across the country. Moreover, sales figures indicate higher readership corresponding to states with urban centers such as New York (Northeast), Chicago (Midwest), and Los Angeles (West).

This assertion is presumptive, and the conclusion I suggest is not shocking. As a print product rooted in the magazine industry, the distribution structures supporting those publications facilitated the comic book’s consumption.[4]

What then is the value of the ABC data? I believe it lies in supporting our ability to seek gradation to the narrative of superhero and readership. For example, as more companies capitalized on audience demand, characters such as Captain Marvel garnered dedicated readership. In March 1946, the Fawcett publication sold 936, 605 units. While lagging behind Superman in sales, we can see how this “Golden Age” of readership played out state by state. ABC data allows us to know the depth of engagement in Florida, a state that doesn’t often play a central role in comic book narrative but with a distinct link to the medium. Miami served as the home to Fleischer Studio, which produced classic Superman animated shorts. The state showed a consistent comic readership.

These numbers add depth to the Golden Age of comic book readership. Like the comics themselves, the visual narrative of readership encourages thinking anew about the impact of the superhero and fosters pathways for further inquiry.

Julian C. Chambliss is Professor of English with an appointment in History and the Val Berryman Curator of History at the MSU Museum at Michigan State University. In addition, he is co-director for the Department of English Digital Humanities and Literary Cognition Lab (DHLC) and a core participant in the MSU College of Arts & Letters’ Consortium for Critical Diversity in a Digital Age Research (CEDAR). His research interests focus on race, culture, and power in real and imagined spaces. His recent writings on comics have appeared in More Critical Approaches to Comics (2019) and The Ages of Black Panther (2020). He has designed museum exhibitions, curated art shows, and created public history projects that trace community, ideology, and power in the United States. He is co-editor of Ages of Heroes, Eras of Men: Superheroes and the American Experience (2013), Assembling the Marvel Cinematic Universe: Essays on the Social, Cultural and Geopolitical Domain (2018) and Cities Imagined: The African Diaspora in Media and History (2018). Chambliss comics and digital humanities project include The Graphic Possibilities OER, open educational resources focused on comics and Critical Fanscape, a student-centered critical making project focus on comics. In addition, he serves as faculty lead for Comics as Data is an ongoing collaborative project at Michigan State University that examines library catalog data to explore geographies of publishing and library collecting policies in North American comics.

Website: www.julianchambliss.com

Twitter: @JulianChambliss

[1] Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 1.

[2] Alex Boney, “Superheroes and the Modern(Ist) Age,” in What Is a Superhero?, ed. Robin S. Rosenberg and Peter Coogan, 1 edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 42–43.

[3] Richard Reynolds, Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology (University Press of Mississippi, 1994).

[4] Jörn Ahrens and Arno Meteling, Comics and the City Urban Space in Print, Picture, and Sequence (New York: Continuum, 2010); Ian Gordon, Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890-1945 (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002).