Visualizing Comic Book Circulation Narratives

by Joshua Plencner

Histories of the American comic book industry often carefully reconstruct insider interviews, mythologized anecdotes, and speculative fanlore to triangulate their claims about circulation and sales figures.[1] As a social scientist who mostly cosplays in the humanities, I find this method fascinating because it makes the question of comic book circulation itself a kind of historiographical and cultural project, the stakes of which help establish our collective commonsense about the comics publishing industry is (or was) and what we ought take that to mean. Recalled through the lens of fan-constructed “eras” of comics history, we’re presented with what might be considered “circulation narratives” – or stories describing relative market footprints of the largest companies operating within the industry’s so-called “Golden” and “Silver Ages,” and so on, as well as the competitive publishing strategies that explain such footprints. Comic book circulation narratives are necessarily suggestive. They suppose much about the industry, illustrating supposition with rich memory-work and fabulation.

When numerical data show up in comics scholarship – whether confirming or subverting comics commonsense – the most robust analyses rely on reports published in fanzines and trade magazines, which are themselves usually based on numbers derived from unaudited Publisher’s Statements of Ownership and the advertising periodical directory publisher N.W. Ayer & Sons.[2] For example, in attempting to describe “peak” comic book circulation, Jean-Paul Gabilliet’s Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books reproduces circulation data from 1933-1970 reported by Michelle Nolan in The Comic Book Marketplace, as well as claims about overall industry circulation made by Robert Klein in Alter Ego (based on the Ayer’s Guide) and Robert Beerbohm in several archived internet forums (based on reporting in Newsdealer Magazine).[3] We can ask plenty of questions about the reliability of such nested citations – and Gabilliet acknowledges those limitations explicitly – but in the end he arrives at the credibly triangulated claim that “the economic peak of the industry was 1952, when 3161 comic books were published for an overall circulation around 1 billion” copies (2010, 46).

Chart tracking total publications from American comic book publishers by year, compiled by Gabilliet (2010, p. 47) and based on reports by Nolan in The Comic Book Marketplace.

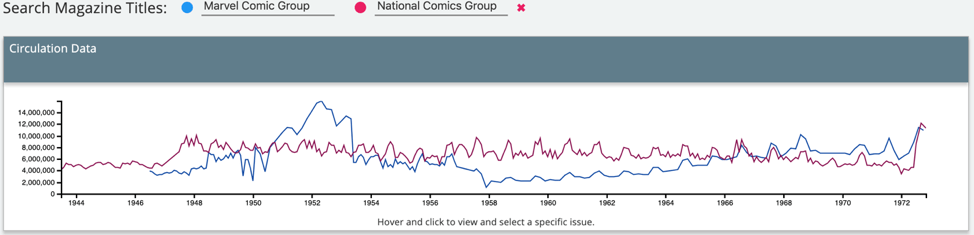

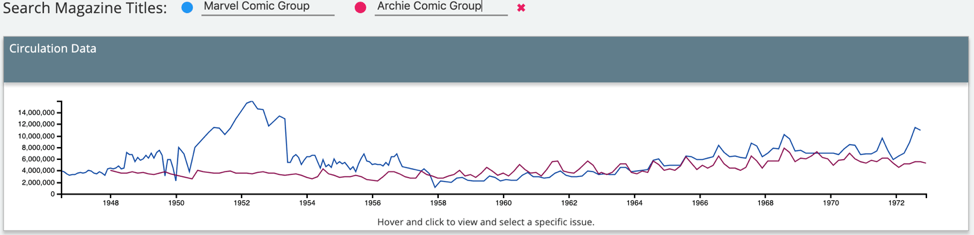

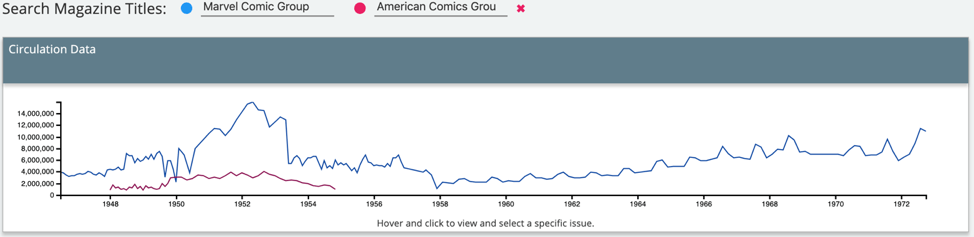

Extending and deepening our understanding of the “economic peak” of the comic book industry, data collected from the Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC) and visualized here through Brooks Hefner and Ed Timke’s Circulating American Magazines Project provides much needed detail on the comics circulation question. Indeed, it provokes even richer questions that poke holes in some comics commonsense. Returning to Gabilliet’s claim above, by comparing ABC circulation data from two well-known publishers – National Comics Group (the corporate predecessor to DC Comics) and Marvel Comic Group – the data visualization shows that not only did overall circulation spike in 1952, but that the spike was likely spurred by Marvel publications.

When including comparisons of Marvel to Archie Comics Group and American Comics Group, we can further emphasize the point that no other publisher’s circulation data collected by Hefner and Timke mimics what happens at Marvel over this same time period.[4]

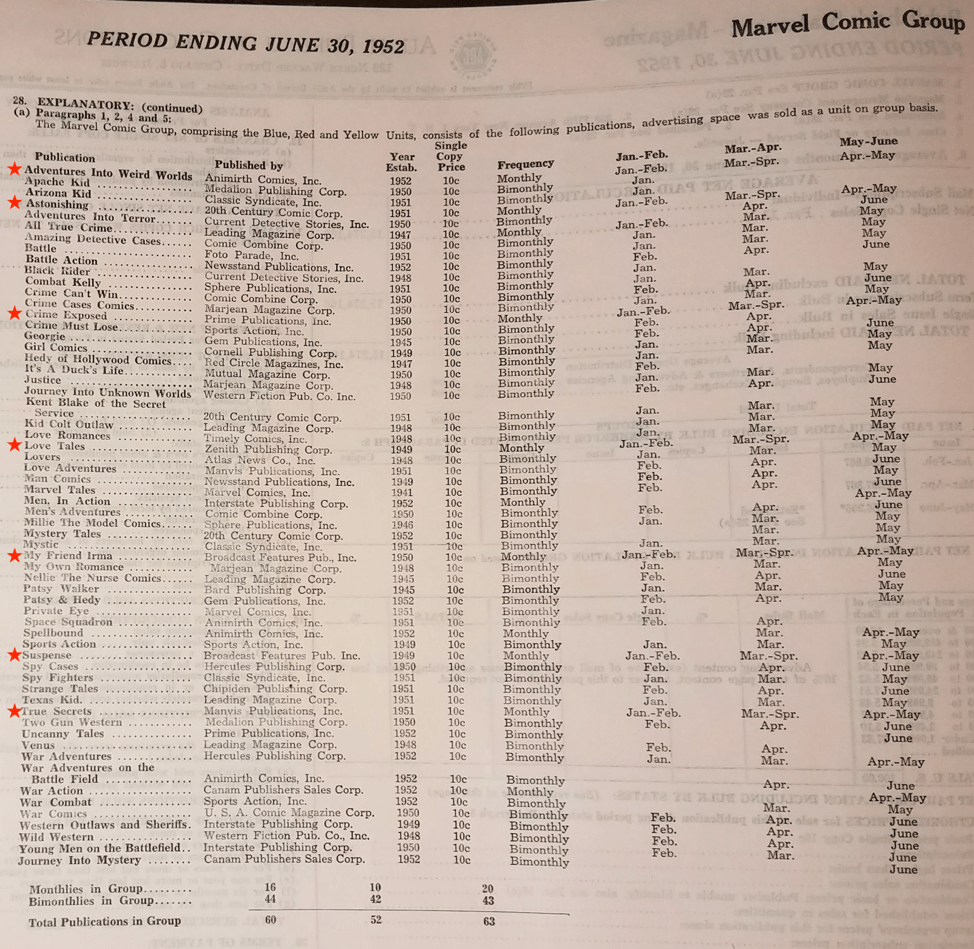

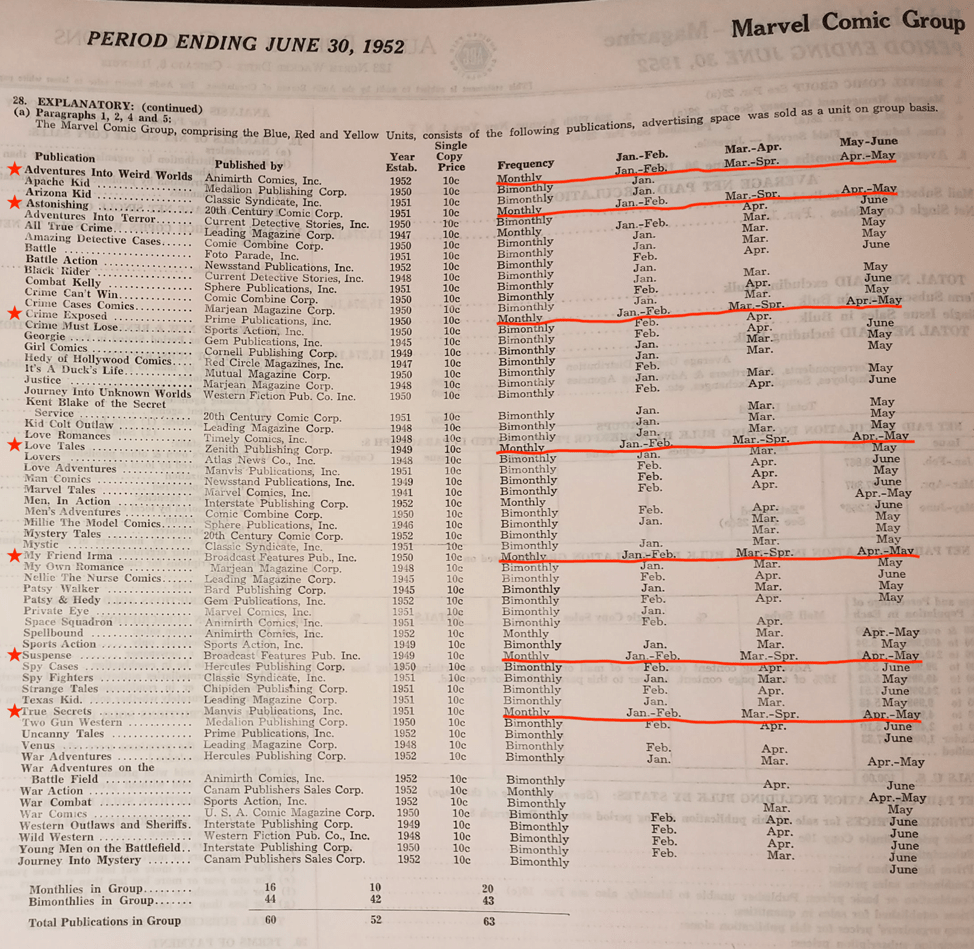

So how might we explain this spike in circulation, or ask more questions about Marvel’s influence on overall circulation through the early 1950s? Comics historians writing about these years tend to highlight the cultural impact of War, Crime, and Horror genre comics, which fed moral panics of the late 1940s and early 1950s, prompted the publication of psychologist Fredric Wertham’s damning Seduction of the Innocent and its spectacular airing in US Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency hearings in April and June of 1954, and ultimately triggered the creation of the infamous Comics Code Authority in 1955. But by digging further into the tabulated ABC data, several scanned images of which Hefner shared with me, I found seven titles that suggest we ought to look beyond War, Crime, and Horror genres to help explain the circulation spike in 1952. The titles, indicated on the table below, are Adventures into Weird Worlds, Astonishing, Crime Exposed, Love Tales, My Friend Irma, Suspense, and True Secrets.

Audit Bureau of Circulation table for Marvel Comic Group, January 1 – June 30, 1952. Image courtesy of Circulating American Magazines Project co-director Brooks Hefner.

Why do these titles show evidence of influencing Marvel’s spiking circulation? As the highlighted table below indicates, from January 1952 through June 1952, each of these titles were published on both a monthly schedule (labeled in columns as “Jan.-Feb.,” “Mar.-Apr.,” and “May-June”) as well as a quarterly schedule (labeled in the “Mar.-Apr.” column as “Spr.,” or “Spring Quarter”).[5] This means Marvel published seven issues of each of these seven titles during the first six months of the year, flooding the market with product to the point that these specific issues would have had multiple sequentially-numbered issues for sale on newsstands at the same time.[6] Essentially, what this table suggests is evidence of Marvel pushing (and actually discovering, given the subsequent drop-off in circulation) the upper boundaries of market saturation. Surprisingly, War genre titles – of which Marvel published roughly a dozen during the first six months of 1952 – were not a part of this experimental publishing push.

Audit Bureau of Circulation table for Marvel Comic Group, January 1 – June 30, 1952. Image courtesy of Circulating American Magazines Project co-director Brooks Hefner.

One title among this lot that might be surprising for some, and one that is almost totally lacking any critical historical analysis, is teen comedy My Friend Irma. Written by Stan Lee with art by the inimitable Dan DeCarlo, Marvel’s My Friend Irma comic book series was a spin-off of a major contemporary media franchise. Originally a popular CBS serial radio program debuting in 1947, My Friend Irma jumped to feature film in 1949, found publication in comic strips and comic books in 1950, and finally transitioned to the small screen as a CBS television show, airing for three seasons from 1952-1954.

It may be a forgotten footnote in the history of American comic book publishing, but given its apparent and surprising role in the “economic peak” of the industry in 1952, ABC’s circulation data suggest that Marvel’s My Friend Irma is worth studying further. It points to some interesting holes in our commonsense understanding of early 1950s publishing, and it raises relevant critical questions regarding comics’ long-term corporate and commercial relationships with complimentary media forms. What does it mean that, at its most commanding early market position, Marvel Comic Group apparently relied on a licensed transmedia property to drive circulation and sales? Today, with the “convergence” of the Marvel Cinematic Universe across nearly every viable media space (and with the DC Extended Universe not far behind), transmedia saturation of popular culture is the norm. But by digging into what happened to comic book circulation in 1952 – and augmenting some received commonsense with new data visualizations – we can better contextualize transmedial analysis to tell better, richer, and more complex circulation narratives.

Joshua Plencner is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at SUNY Oswego. His research on politics, culture, and identity has been published in New Political Science, HA: The Journal of the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College, Black Perspectives, Artists Against Police Brutality, The Middle Spaces, and by the University Press of Mississippi.

[1] Examples of comic book fanzines, trade magazines, and other publications regularly featuring interviews with comics industry professionals and critical analysis of industry trends are far too numerous to list here. For very recent analysis and interviews, I highly recommend Hassan Osmane-Elhaou’s digital magazine PanelxPanel. For its longstanding influence and crystal-clear editorial perspective, The Comics Journal remains reliable. Other periodicals, like Wizard Magazine, Amazing Heroes, Marvel Age, Comics Buyer’s Guide, the various Overstreet titles, as well as earlier (and more difficult to track down) fan publications like Jerry Bail’s Alter Ego and the influential SF and comics fanzine Xero, all offer mixtures of criticism, interviews, and industrial analysis. Likewise, circulation narratives are extremely common in popular comics histories, biographies, and scholarship. Many examples exist, but for an especially illustrative case, see: Howe, Sean. Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: Harper Perennial, 2012.

[2] Data published by Comichron.com, a standby source for circulation numbers in recent comics scholarship, is based on two sources: unaudited “Publisher Statements of Ownership” filed with the US Postal Service and regularly printed inside published comic books, as well as “pre-orders” from specialized comic book retailers placed with major comic book distribution companies such as Diamond Comic Distributors, Inc. For more information, see: https://www.comichron.com/index.php

[3] For the full explanation of method, citation strategy, and likely historical accuracy referenced here, see: Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2010, p. 46-49, 328.

[4] A strong note of caution here: while the Marvel Comic Group data visualization indicates a clear spike in circulation, suggesting influence on overall comic book circulation, the Circulating American Magazines Project does not collect data from all comic book publishers in the market. The absence of data from Dell Comics, in particular, which was as large and influential as National and Marvel during this era, makes definitive claims impossible. A more satisfying picture of overall circulation requires inclusion of Dell, and would benefit a great deal from contemporaneous data on EC Comics, Harvey Comics, Charlton, Lev Gleason Publications, and several other mid-size publishers.

[5] Here it actually looks like Marvel’s dual Monthly/Quarterly publication schedule surpasses ABC’s ability to account for the number of any given title’s issues published per year. If even the independent auditors couldn’t keep pace with this schedule it’s no wonder that fans quickly backed away from such high-pressure circulation too.

[6] Comic books cover-dated as “Spring Quarter” were traditionally released for sale alongside “April” cover-dates.