The Pulps at War: Militarized Masculinity in Men’s Adventure Magazines

by Gregory A. Daddis

During the Cold War, men’s adventure magazines could be found in magazine racks across the country and in the post exchanges on military bases around the globe. The “macho pulps” trumpeted the exploits of larger-than-life, self-satisfied men, valiant on the battlefield and accomplished in the bedroom. These warrior heroes were physically fit, mentally strong, and resolutely heterosexual.[1]

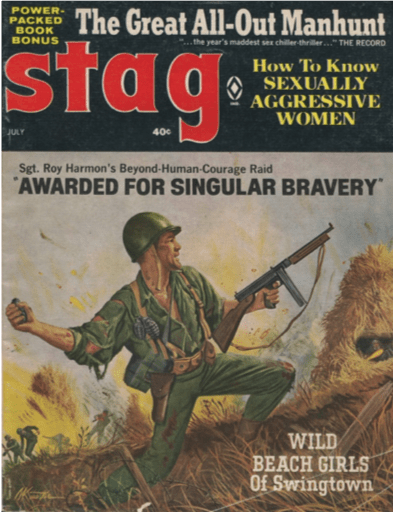

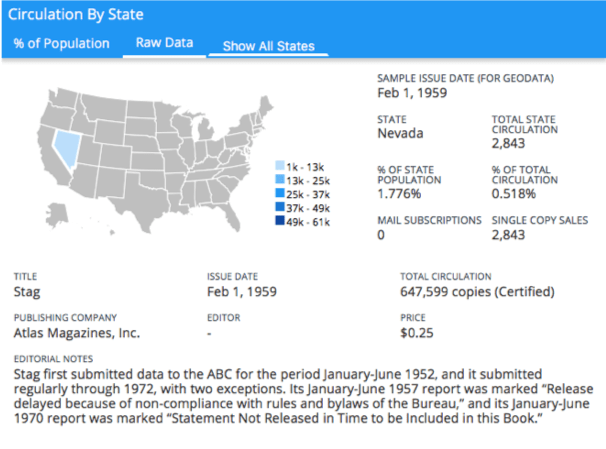

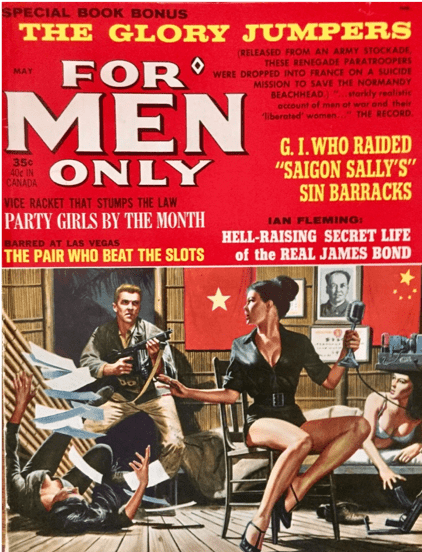

Considered by the era’s cultural critics as “throwaway” consumer kitsch—boasting titles like Climax, For Men Only, and Stag—pulp magazines’ impact on Cold War culture has been largely discounted by scholars. Yet by the mid 1960s, they had a collective circulation of roughly twelve million copies a month. Clearly, these titles were being consumed in high quantities. The February 1, 1959 issue of Stag, for example, sold over 2,800 copies in Nevada alone, an astonishing 1.776% of the state’s total population.[2]

To be sure, the gritty adventure stories that were the lifeblood of postwar macho pulps struck a chord with many American men seeking inspiration, stability, and identity in an uncertain postwar world. Men’s adventure magazines both manifested these popular fears and offered an antidote for men struggling to prove their manhood. In many ways, the construction of warrior heroes in the pages of the macho pulps was a response to many Americans’ fears inspired by the twin forces of international communism and a postwar consumer culture at home.[3]

As a corrective, adventure magazines in the 1950s and 1960s depicted the ideal man as both heroic warrior and sexual conqueror. War stories illustrated the exploits of courageous soldiers, fighting against the “savage” enemy in foreign lands, and defending democracy in a harsh world where the threat from evil actors always seemed lurking. Sex underscored nearly all of these tales, with pulp heroes rewarded with beautiful, seductive women as a kind of payoff for their combat victories.[4]

Adventure mags also sought to strike a chord with their primary readership: working-class young men, the same demographic that disproportionately fought a long and bloody war in South Vietnam. Working-class males read flashy stories of their fathers’ generation who, during World War II, not only conquered their enemies but women as well.[5] These men, then, consumed a form of masculinity that was tough, rebellious, and decidedly anti-feminine. Read a different way, however, the magazines might also be seen as a form of entertainment and escapism from deep class anxieties and fears about not measuring up in a rapidly changing postwar society.[6]

Yet it was the hypermasculine narratives, not the subtext of anxiety, that helped shape the attitudes of young men who went to war in Southeast Asia during the mid to late 1960s. One lieutenant recalled how “men’s magazines were associated with home, and we read them, owned them, and traded them as if they were gold.” Another veteran remembered that the “most widely-read literature among the guys” were “comic books and adventure stories,” filled with pictures of “some guy killing somebody and the bare-breasted, Vietnamese-type, Asian-looking woman.”[7] In fact, men’s adventure magazines regularly appeared on the list of top sales in the post exchange (PX) system in Vietnam. Thus, we might think of these magazines as both cultural text and cultural phenomenon. Not only did they foster ideas about what it meant to be a man, but they also helped their readers negotiate those meanings within their daily lives, both at home and abroad.[8]

Indeed, in many of the pulps, letters to the editor contained feedback from soldiers deployed overseas, including those serving in Vietnam. Many veterans themselves wrote stories for adventure magazines, suggesting important linkages between war and society during the 1950s and 1960s, and as such they were one of the few venues that specifically connected martial valor with sexual entitlement and violence with virility. Neither comics nor television shows nor John Wayne movies so purposefully melded war with sex. If there was a dominant narrative at play in these magazines, that paradigm unabashedly fused together violence and sexuality. Such a paradigm would reap horrific rewards on the battlefields of Southeast Asia during the American war in Vietnam.

Gregory A. Daddis is a professor of history and holds the USS Midway Chair in Modern US Military History at San Diego State University. He specializes in the history of the Vietnam Wars and the Cold War era and has authored five books, including Pulp Vietnam: War and Gender in Cold War Men’s Adventure Magazines (2020) and Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam (2017). Daddis also has published numerous journal articles and several op-ed pieces commenting on current military affairs, to include writings in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and National Interest magazine.

[1] The term “pulps” is a contested one. Hardcore fans of pre-World War II pulp magazines, for example, chafe when the term “pulp” is applied to anything else. Because men’s adventure magazines share thematic and artistic DNA with these classics pulps, I use “pulp” as an adjective to describe a style of media that involved action and adventure and was more gritty than cerebral.

[2] Lee Server has described the pulps as “publishing’s poor, ill-bred stepchild.” Danger is My Business: An Illustrated History of the Fabulous Pulp Magazines (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993), 15. On masculinity in this genre, see David M. Earle, All Man! Hemingway, 1950s Men’s Magazines, and the Masculine Persona (Kent, Oh.: The Kent State University Press, 2009).

[3] On the relationships between insecurity, paranoia, and masculinity, see Jonathan Mitchell, Revisions of the American Adam: Innocence, Identity and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Continuum, 2011).

[4] Savages in Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 11. Michael Kimmel argues that in tales like these, men were rewarded with sexual rewards “as a kind of masculine payoff.” Manhood in America: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 254.

[5] Christian G. Appy found that “Roughly 80 percent came from working-class and poor backgrounds.” Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 6.

[6] According to Peter Haining, the “pulps were not just intended to entertain the reader—they were also meant to make him feel better about himself, his prospects, and especially his sex life.” The Classic Era of American Pulp Magazines (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2000), 21.

[7] Gold in Ron Milam, “Missing Home: How Popular Culture Was Used to Remind Us of What We Were Missing,” in The Vietnam War in Popular Culture, Vol. 1: During the War, ed. Ron Milam (Santa Barbara, Ca.: Praeger, 2017), 61. Widely-read literature in Tom Engelhardt, “An Air-Force Hospital: The War-Wounded Come Home,” Dispatch News Service International, 21 June 1971, 6.

[8] PX data in “Minutes of Meeting of Joint Vietnam Regional Exchange Council,” 29 April 1969, Folder 301-05, Box 3, USARV, Non-Appr. Funds Div, RG 472, National Archives II, College Park, Maryland. Text and phenomenon in Bethan Benwell, ed., Masculinity and Men’s Lifestyle Magazines (Malden, Ma.: Blackwell, 2003), 8.