What is a mass-circulation magazine?

by Faye Hammill

What is a mass-circulation magazine? Some twentieth-century American titles reached peak circulations of seven, eight or nine million. This meant, as the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC) data demonstrates, that up to five per cent of the population in some U.S. states would have been reading the same magazine: whether it was the Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, or the Saturday Evening Post. These periodicals conform to Richard Ohmann’s definition of mass culture: “voluntary experiences, produced by a relatively small number of specialists, for millions across the nation to share, in similar or identical form, either simultaneously or nearly so”.[i]

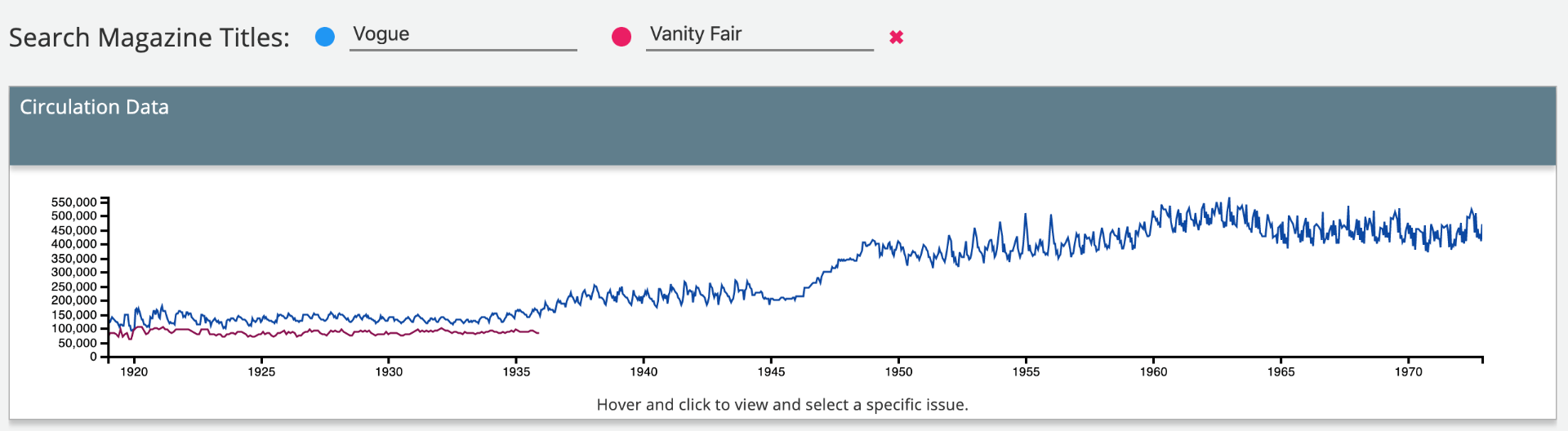

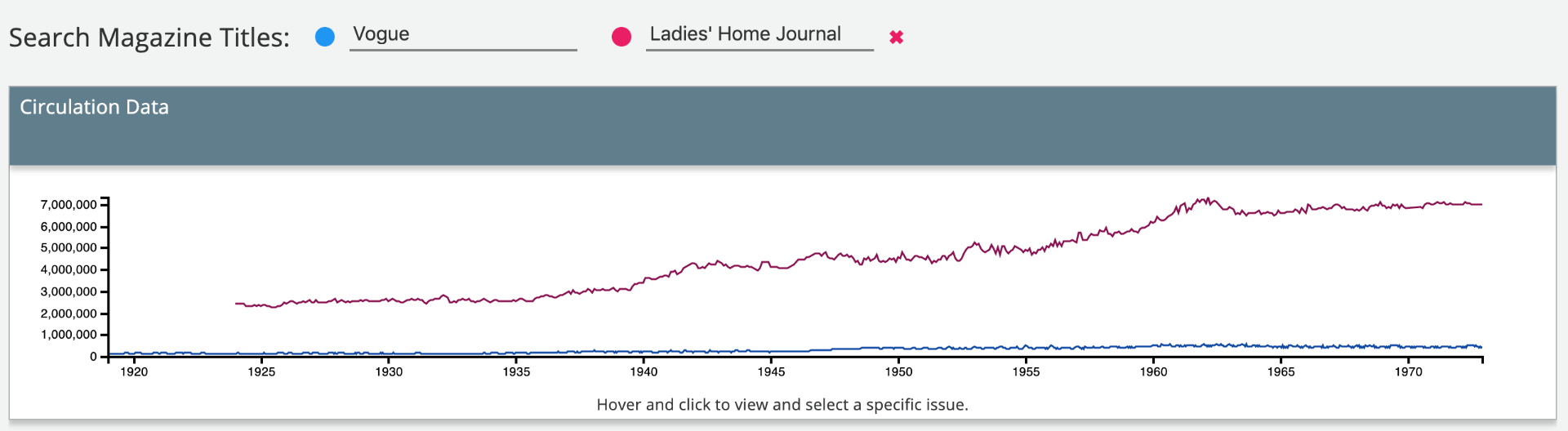

I’ve been using the visualisation functions on the “Circulating American Magazines” website to plot the audience figures for these enormously popular titles against those of two magazines I work on: Vanity Fair and American Vogue. Michael Murphy categorizes the jazz-age Vanity Fair, established in 1913, as “a piece of market-driven mass culture”,[ii] while Mark Morrisson classes it with the Ladies’ Home Journal and Cosmopolitan as a “mass market magazine”.[iii] Alison Matthews David comments that during the two decades following its launch in 1892, Vogue changed “from an amateur, Eurocentric social gazette that focused on fantasies of the colonial past” into “a professional, self-confident mass-circulation magazine”.[iv] For Sophie Kurkdijan, during the interwar years, Vogue was “a cog in the machine of the emerging mass culture”.[v]

Most critics, then, label these two Condé Nast titles as “mass” magazines. Yet the ABC data shows that their circulation was a fraction of that of women’s service monthlies. During the twenties and thirties, Vogue printed between 120,000 and 150,000 copies of each issue, while Vanity Fair trundled along just underneath, in the zone between 70,000 and 100,000.

After the 1936 merger of the two titles, there was a small rise in Vogue‘s circulation, but it didn’t get above 200,000 until the war years. The issue for January 1955 was the first to sell half a million copies. The Ladies’ Home Journal, by contrast, was reaching about 3 million readers by the 1930s.

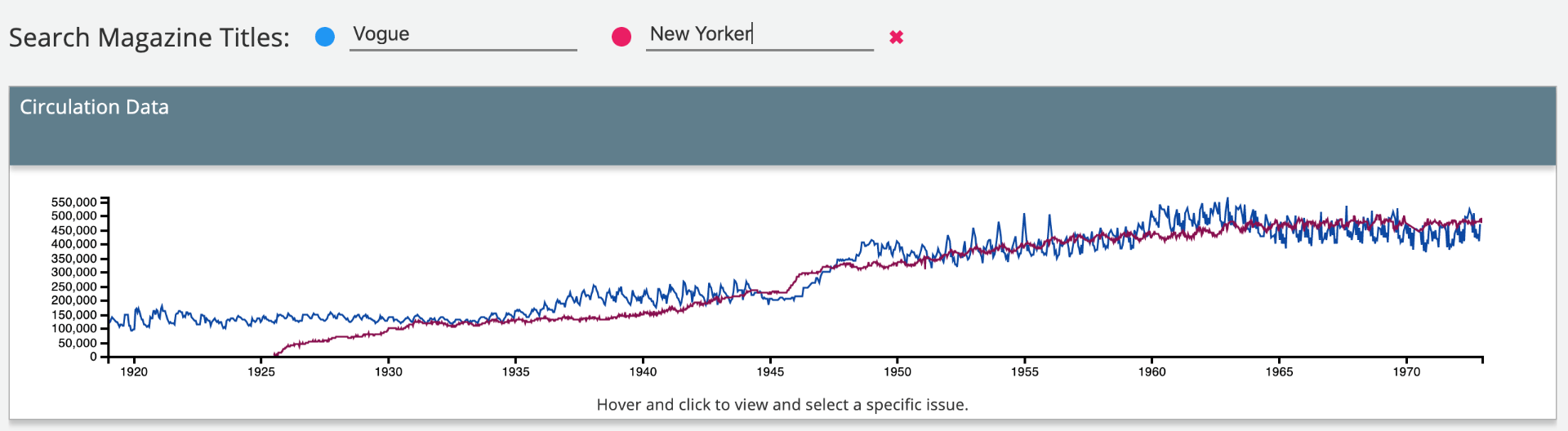

Vogue never even came near the circulation of the other expensively-produced “smart” magazines, such as Esquire or Hearst’s The Smart Set (discussed by Craig J. Saper in another post on this site). In fact, a much more apt comparison for Vogue, in terms of audience size, is The New Yorker, which was likewise marketed to a restricted audience of educated readers with high disposable incomes. The New Yorker’s circulation showed much less seasonal variation than Vogue‘s, but in terms of year-on-year figures, the two titles coincide quite closely throughout the period from the 1930s to the 1970s.

And yet we tend to consider The New Yorker an intellectual periodical, less directly implicated in the logic of capitalism than are the fashion magazines.

So why are titles such as Vogue and Vanity Fair consistently categorised as “mass-market”, even though they never reached a genuinely “mass” audience? I think there are three reasons. First, many critics writing about them are primarily interested in the extent to which they showcased modernism. Therefore, they compare Vanity Fair and Vogue to the experimental little magazines of the early twentieth century, which had subscription lists of only a few hundred. The second explanation is the consumer-oriented content of the Nast periodicals, and their growing dependence on advertising revenue. This business model generates certain assumptions about their ideological orientation and relationship to their audience. The third reason is brand recognition. Our reading of the jazz age Vanity Fair is inflected by an awareness of the commercial success of its new incarnation, launched in 1983. And, as the website of the “Robots Reading Vogue” project puts it, “Few magazines can boast being continuously published for over a century, familiar and interesting to almost everyone.” Indeed, the influence of both Vogue and Vanity Fair as tastemakers has always extended far beyond the group of readers who subscribe or purchase copies. They are not, in fact “mass-circulation” titles, but they have a role in mass culture nevertheless, because of their powerful position in the cultural field of periodical publishing.

Faye Hammill is Professor of English Literature at the University of Glasgow. Her most recent books are Modernism’s Print Cultures (2016, with Mark Hussey) and Magazines, Travel, and Middlebrow Culture (2015, with Michelle Smith).

[i] Richard Ohmann, Selling Culture: Magazines, Markets, and Class at the Turn of the Century (London: Verso, 1996), p. 14.

[ii] Michael Murphy, “One Hundred Per Cent Bohemia: Pop Decadence and the Aestheticization of the Commodity in the Rise of the Slicks”, in Kevin J.H. Dettmar and Steven Watt (eds), Marketing Modernisms: Self-Promotion, Canonization, Rereading (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1996), pp. 61-89, at p. 68.

[iii] Mark S. Morrisson, The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences and Reception, 1905-1920 (Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 2001), p. 176.

[iv] Alison Matthews David, “Vogue’s New World: American Fashionability and the Politics of Style”, Fashion Theory, 10:1-2 (2006), 13-38 at p. 35.

[v] Sophie Kurkdijan, “The emergence of French Vogue: French identity and visual culture in the fashion press, 1920-40.” International Journal of Fashion Studies, 6:1 (2019), 63-82, at p. 65.