Circulating Physical Culture

by Catherine Keyser

Physical Culture, August 1922 (Ball State University Digital Media Repository)

Physical Culture, May 1927 (Ball State University Digital Media Repositor)

The events of recent months have reminded us that the topics of health and wellness can tap into media consumers’ deeply held fears and mobilize their wildest political imaginations. Through social media memes, QAnon courted adherents in the “wellness community.”[1] Advice about the body quickly becomes reflections on the body politic. To be clear, in the consideration that follows, I do not mean to conflate QAnon’s conspiracy theories with the precepts of diet and exercise guru Bernarr Macfadden, who ran for Florida senator in 1940 but did not, as far as I know, believe that an underground network of Hollywood stars and Democratic politicians were abusing and cannibalizing children.[2] Nonetheless, Macfadden’s potent blend of white supremacy, diet quackery, and exercise fanaticism laid the groundwork for his wide-ranging career in print. Macfadden began with one magazine championing physical and mental health (Physical Culture magazine) and ultimately published a range of periodicals that seem generically distinct but share the biopolitical investments of the former (True Stories, Photoplay). Readers who subscribed to Physical Culture were seeking diet and exercise tips. Those who read True Stories and Photoplay might have come there seeking salacious confessions or star profiles, but the advertisements and the content reflected the biopolitical fantasy of whiteness and wellness that Macfadden made his métier.[3]

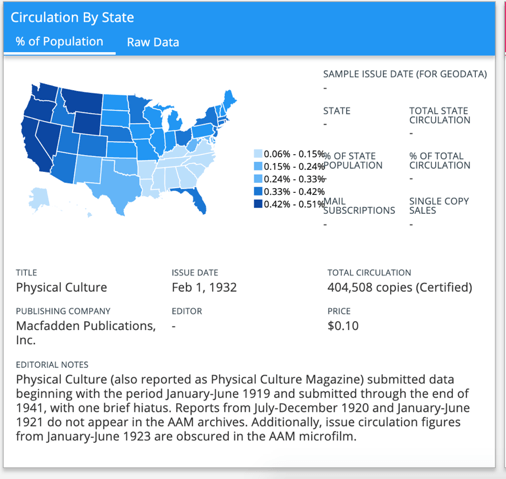

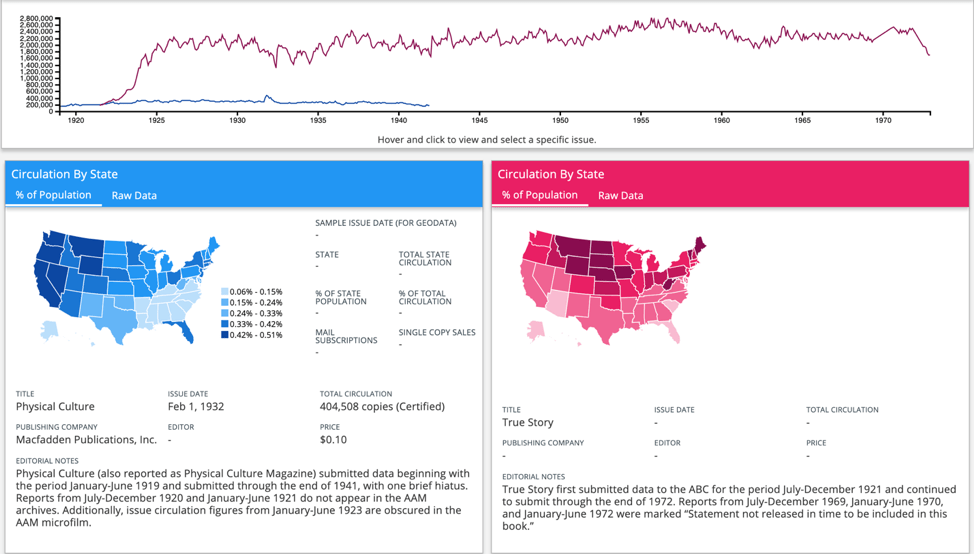

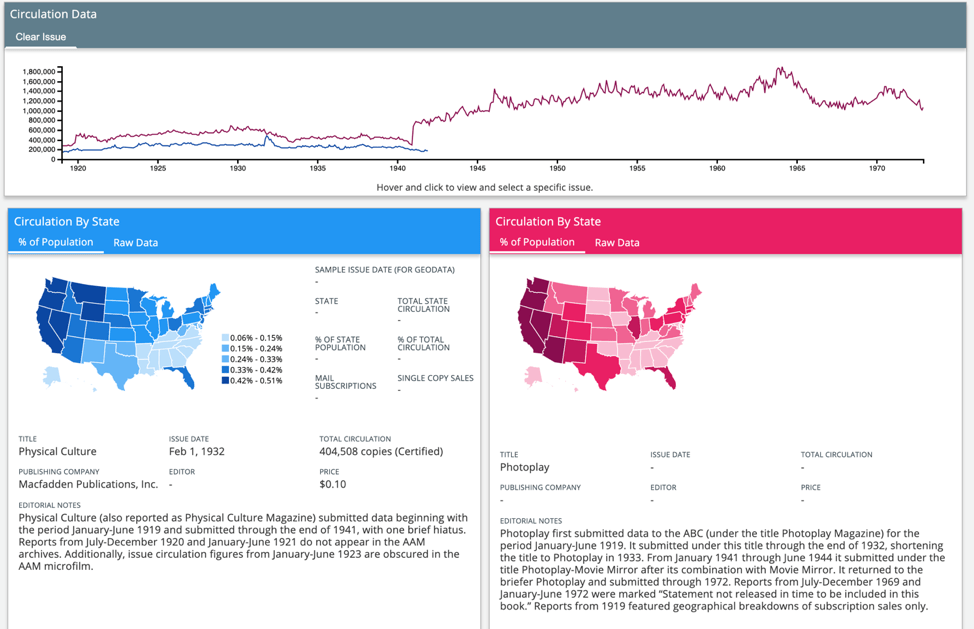

Physical Culture played into an ideal of frontier masculinity that may explain its strong circulation numbers in the West. The magazine contained some expressly regional content. In an early issue, a reader inquires about a physical culture settlement in New Mexico.[4] Physical Culture also plumbed U.S. mythologies associated with the West, praising indigenous diets and midwifery with imperialist nostalgia.[5] Macfadden published fiction by Jack London, reinforcing that fantasy of white masculinity, northwestern exploration, and the raw elements. The magazine was considered scandalous for its pictures of scantily-clad bodies, which may explain its limited circulation along the Bible Belt. Physical Culture’s versions of muscular manhood and fearless femininity promulgated frank sexuality and clean eating, still hallmarks of California culture.

Whatever the reasons for its regional appeal, Physical Culture modeled a combination of lifestyle advice and romantic escapism. It achieved its highest published circulation numbers with its November 1931 issue.[6] Many of the articles reflect the focus on diet and exercise that the publication initially embraced (“The Wisdom of Yoga,” “Watch Your Weight,” “What Are Vitamins?”) Others are more indirect in their exploration of eugenics and euthenics.[7] Macfadden pens an article on “Beauty and Charm.” A confessional essay, reminiscent of the True Stories’ genre, laments: “I Never Had the Children I Wanted.” Along with this content on diet, exercise, courtship, and parenthood, Physical Culture published fiction: Grace Perkins’ Boy Crazy, a serialized novel about a society girl who marries against her family’s wishes, and Gouverneur Morris’ novella “Health and Money,” the title of which encapsulates the putative desires of the magazine’s readership.[8]

This leap from wellness advice to fictional fantasy provided the formula for Macfadden’s publishing career. Though Physical Culture had solid circulation numbers, True Story began with similar circulation numbers and then blew it out of the water.[9] Photoplay, which Macfadden acquired in the 1930s, also dramatically outpaced it.

Physical Culture told a seductive story: white men and women, sapped by modernity and all its excesses, could achieve physical vigor and renewed sexual desire (as well as desirability) if only they followed Macfadden’s regimens. This story could be translated into other narrative forms, embedded, not in dietary advice, but in fantasy fulfillment. In these less obviously biopolitical genres, readers were coaxed into a view of their bodies as fundamentally transformable. This slippage between advice and fantasy reveals the potency of purity and healthfulness as an ideological pitch for white supremacy. Attitudes about health and wellness shape how media consumers imagine their peers (True Story) and their celebrity crushes (Photoplay). These fantasies carry powerful messages about gender, race, and sexuality and their proper expression through the body. As QAnon demonstrates all too well, media circulates the biopolitics of white supremacy in many guises. MacFadden’s circulation successes anticipate what we see in our own social media moment.

Catherine Keyser is a Professor of English at the University of South Carolina and the author of Playing Smart: New York Women Writers and Modern Magazine Culture (Rutgers UP 2010) and Artificial Color: Modern Food and Racial Fictions (Oxford UP 2020).

[1] EJ Dickson, “Wellness Influencers Are Calling Out QAnon Conspiracy Theorists for Spreading Lies, Rolling Stone, 15 September 2020. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/qanon-wellness-influencers-seane-corn-yoga-105

[2] See Mark Adams, Mr. America: How Muscular Millionaire Bernarr Macfadden Transformed the Nation Through Sex, Salad, and the Ultimate Starvation Diet (New York: Harper, 2009).

[3] See Mark Whalan, Race, Manhood, and Modernism in America: The Short Story Cycles of Sherwood Anderson and Jean Toomer (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2007), 175.

[4] “Comment, Counsel, and Criticism,” Physical Culture vol. 23, no. 6 (June 1910), 161.

[5] Shannon L. Walsh, Eugenics and Physical Culture Performance in the Progressive Era (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 155.

[6] Table of Contents for vol. 66, number 5 reproduced at “The Fiction Mags Index.” http://www.philsp.com/homeville/fmi/t/t5489.htm#A138585

[7] While eugenics prioritized reproduction and bloodlines, “euthenics” championed diet and exercise, the maintenance of a healthful body and family. Helen Veit, Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 104 and 120.

[8] Ann Fabian points out that “Macfadden’s magazines . . . presented a working-class version of a bourgeois culture of consumption . . . [representing] characters in a nonethnic, vaguely middle-class world shaped by constant pulls of needs and desires, sometimes sexual, sometimes commercial, and sometimes, when most successful, both.” Ann Fabian, “Making a Commodity of Truth: Speculations on the Career of Bernarr Macfadden,” American Literary History 5.1 (Spring 1993): 70.

[9] See David M. Earle and Georgia Clarkson Smith, “‘True Stories from Real Life’: Hearst’s Smart Set, Macfadden’s Confessional Form, and Selective Reading,” Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 4.1 (2013): 30-54.