Photoplay’s Fan Nation

Katherine Fusco

Are we all teen girls? Much foundational work on film fandom and the fan magazine in particular has focused on a young, female audience. And for good reason: in work on film audiences such as Shelley Stamp’s Movie Struck Girls and Jackie Stacey’s Star Gazing, feminist scholarship has pushed back against ideas of an uncritical, silly female film viewership of the type encapsulated by Siegfried Kracauer’s essay “The Little Shopgirls go to The Movies,” in which he describes young women perched at the edge of their theater seats learning “to understand that their brilliant boss is made of gold on the inside as well.”[i] Identifying and taking seriously young women’s fandom has been important feminist work that articulates the creativity and social import of teen girls’ and young women’s moviegoing.

The field of fan studies has also wrangled with complex matters of identification as scholars since Laura Mulvey, and including Laura Mulvey herself, have complicated the notion of an entrapping one-to-one form of identification between fans and stars which would posit, for example that young women can only identify with the passive female characters on screen. Critical race studies and queer studies of cinema such as Anna Everett’s Returning the Gaze and Jose Munoz’s Disidentifications have been particularly important for suggesting the way audience members may have identified differently, partially, or not at all.[ii]

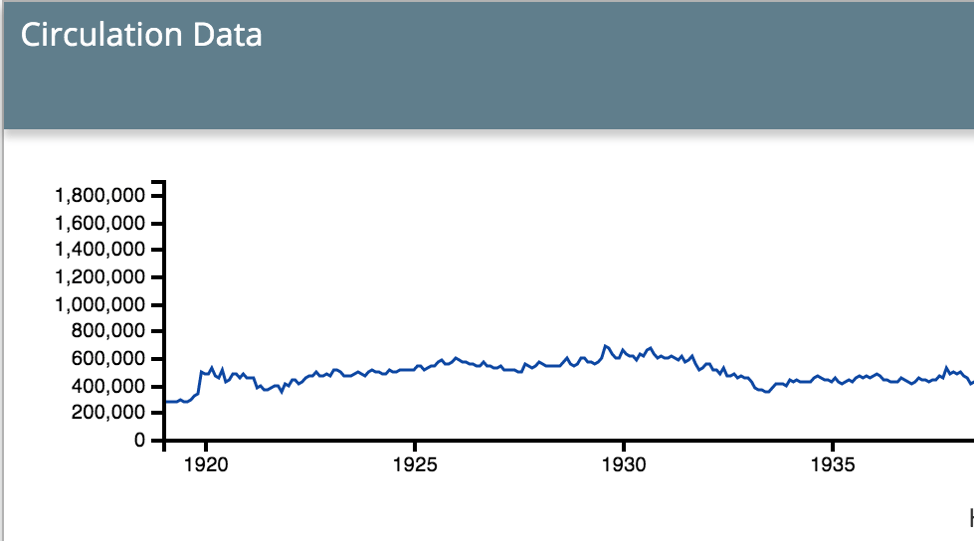

Still, a sense of the fan magazine reader as a teen girl has shaped much of the discussion, including Anthony Slide’s overview Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine.[iii] Looking at the static content of the magazines, it’s easy to understand why this impression has remained. The earliest magazines ran stories derived from films, hence titles such as Photoplay and Motion Picture Story. In the late 1910s, however, Photoplay began shifting its coverage to focus on the lives of stars, quickly establishing its dominance in the field, and others followed suit. As the data visualizations indicate, with the shift to focusing on celebrity, the magazine took off:

Alongside articles about stars and their lives, short stories, and film reviews, the magazines increasingly featured beauty articles, Q&A columns, and letters from fans weighing in on popular actors and actresses of the day. In the 1920s, with columns like these, Photoplay’s editor James Quirk developed an active readership, positioning the magazine as fans’ place to speak back to Hollywood. One example of this solicitation of fan engagement was Quirk’s development of a “Medal of Honor,” awarded by readers who voted on their favorite film of the year. Even after printing, the magazines were remarkably participatory periodicals: research on fan scrapbooks shows that fans continued to see the magazines as interactive, as they cut, pasted, and sometimes improved upon what had been initially presented in the magazines.[iv] Despite the articles emphasizing beauty and romance, which positioned a young woman reader, letters to the editor, Q&A articles, and fan mail columns indicate a more diverse readership. For example, in 1941 a David Lewis of Nova Scotia complained about Photoplay’s negative coverage of war pictures, “In the June issue of Photoplay-Movie Mirror you bewailed the fact that Hollywood is putting far too much emphasis on the heroic struggle of Britain. Perhaps it has never occurred to you that movies are primarily adult fare and that any appeal to the intellect at all must be mature.” Mr. Lewis closes his protest against juvenile fare by making a sarcastic suggestion to the reviewer: “I’m under the impression, Mr. Jordan, that the reluctance to face realities is at the bottom of your trouble. I suggest that you accompany your children to the next Gene Autry picture; I’m sure you will find that refreshing. And the news that Shirley Temple is making a comeback will doubtlessly thrill you no end” (Lewis 20, italics original).[v] It has been hard to know how to read the letters in the fan magazines. How representative a Photoplay reader was the sophisticated Mr. Lewis? While earlier scholars have questioned the validity of “write-in” features, Lies Lanckman has worked to track these letters to real readers, helping contemporary scholars learn to trust the authenticity of published fan mail.[vi]

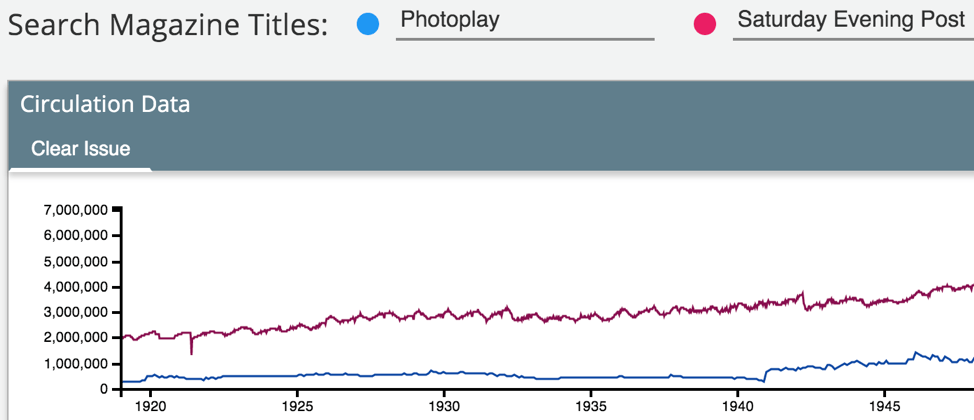

Supporting this anecdotal evidence, Sarah Polley has carefully challenged the notion that the fan magazine phenomenon was exclusively the realm of the teen girl by tracking circulation against national demographics. In her carefully-documented investigation of fan magazine circulation for the period 1914-1965, she contextualizes fan magazine circulations and the spectrum of readers likely for each issue against U.S. demographic information. Based on a premise of approximately three readers per copy, the reader spectrum during this period ranges between an average of between 2.3 and 10.2 million readers of fan magazines. Given that the number of teen girls in this same period averages just under eight million, Polley concludes “it is unlikely that there were enough teenage girls with the disposable income to purchase fan magazines to completely constitute the readership spectrum” (67).[vii] Working with the Circulating American Magazine’s visualization tool, we get a picture of the fan magazines’ expansive reach, as well as the waxing and waning fortunes of the various periodicals. For example, Photoplay’s dominance over time is clear, when measuring the magazine against some of the smaller magazines. More importantly, however, we see further evidence of Polley’s point when running Photoplay’s circulation numbers against those of less special-interest magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. On August 1, 1929, Photoplay reached a high point of 687,087 copies (a high not seen again until the magazine’s 1941 merger with Movie Mirror). The general interest Saturday Evening Post had a circulation of 2,794,705. One special-interest magazine in the fan category, Photoplay was circulating at a rate of about 25% of the bigger magazine.

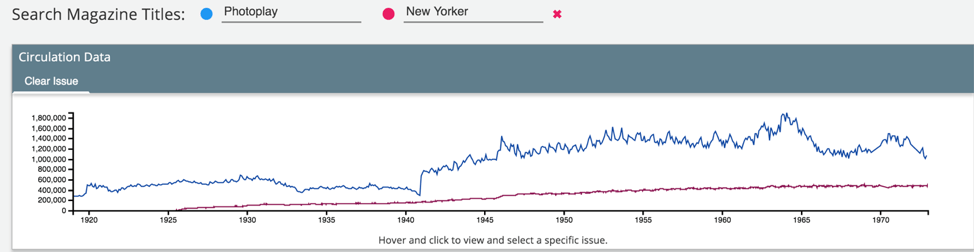

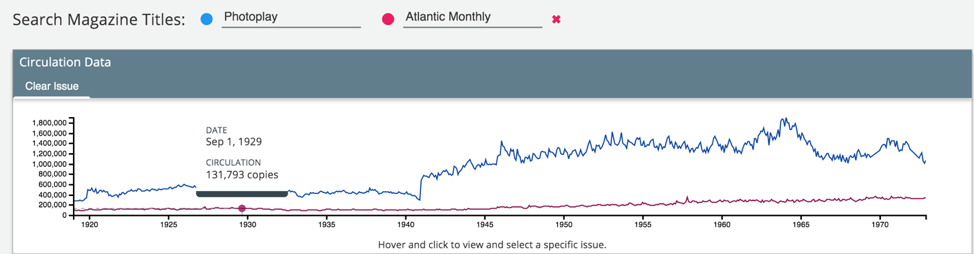

Compared to widely circulated high-brow magazines such as The Atlantic Monthly or The New Yorker, Photoplay positively dominates. Given that Photoplay was merely one among many fan magazines, Polley’s points seems clearly demonstrated: there simply aren’t enough teen girls to account for such numbers.

Why does it matter? What do we get from shaking loose our engrained notions of fan magazine readership? Does this threaten feminist critical work that has showcased the delightful creativity of the young woman movie fan? I’d suggest that it need not. As the data sets collected here show, culture that was coded as young and female was popular with a broad swath of Americans. If anything, we might see the datasets as emphasizing the importance and dominance of female youth culture, sometimes to the consternation of fans like the one quoted above. The data suggest interesting questions about how readers outside of this demographic band navigated the magazines’ beauty and romance articles that hailed a young, female readership. What partial or complex identifications were taking place here? As the Circulating American Magazines’ visualizations suggest, while the fan magazines may have framed themselves as teen girl culture, lots of other people were consuming it too.

Katherine Fusco is Associate Professor of English and the incoming director of Core Humanities at the University of Nevada, Reno. She is the author of two books on film and U.S. culture: Silent Film and U.S. Naturalism (Routledge) and Kelly Reichardt: Emergency and the Everyday (with Nicole Seymour, Illinois). Her articles have appeared in journals such as Studies in the Novel, Modernism/Modernity, Modern Fiction Studies, Adaptation, Cinema Journal and PMLA. Her article “Sexing Farina: Our Gang’s Episodes of Racial Childhood” received the MLA’s prestigious William Riley Parker Prize. Additionally, Katherine has written essays about popular culture, motherhood, and feminism for outlets such as The Atlantic, Harper’s Bazaar, Avidly, and Public Books. She is currently completing a book about 1920s and 1930s celebrity and identification.

[i] Stamp, Shelley. Movie Struck Girls: Women and Motion Picture Culture after the Nickelodeon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. Stacey, Jackie. Star Gazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship. New York: Routledge, 1994. Kracauer, Siegfried. “The Little Shopgirls go to the Movies,” The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Ed. And Trans. by Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. 291-306, 300.

[ii] Everett, Anna. Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909-1949. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001. Munoz, Jose. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

[iii] Slide, Anthony. Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine: A History of Star Makers, Fabricators, and Gossip Mongers. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010.

[iv] I learned about this last practice from Denise Mok’s presentation on a fan who “fixed” magazines in her scrapbooks by coloring in blemishes from the printing process and also occasionally changed stars’ appearances by collaging or marking to better suit their images to her liking. Mok, Denise “Puzzling (Im)Perfections: Manipulations and Materiality in Edith Nadajewski’s Face Saturated Star Scrapbooks (1924-1990s).” Modernist Studies Association Conference. 19 October 2019.

[v] Lewis, David in “Speak for Yourself,” Photoplay. September 1941, 20-23.

[vi] Lanckman, Lies. “In Search of Lost Fans: Recovering Magazine readers, 1910-1950. Ed. Tamar Jeffers McDonald and Lies Lanckman. Star Attractions: Twentieth-Century Movies Magazines and Global Fandom. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019, 45-60.

[vii] Polley, Sarah. “A Spectrum of Individuals: U.S. Fan Magazine Circulation Figures from 1914 to 1965.” Star Attractions: Twentieth-Century Movies Magazines and Global Fandom. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2019, 61-80.