Black Mask and the Mysteries of Circulation

by Brooks E. Hefner

My first encounter with the ABC Blue Books occurred when I was trying to run down information on claims made by Erle Stanley Gardner to Black Mask editor Joseph T. Shaw and circulation manager Philip Cody in letters held at the Harry Ransom Center. Gardner was concerned about the direction that the now legendary crime fiction magazine was taking under Shaw; it seemed to him that Shaw’s promotion of writers like Dashiell Hammett was making the pulp magazine too “arty” and alienating its core readership. He imagined that the appearance of Hammett actually corresponded with a drop in the magazine’s circulation.[1] As a researcher, I was curious if Gardner’s instinct about pulp readership was correct: were pulp readers picky enough to reject Hammett’s writing? I had seen something about the A.B.C. Blue Book of Publisher’s Statements in David Earle’s Re-Covering Modernism, so I went in search of these curious volumes.[2]

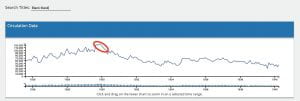

It turns out that Gardner was dead wrong. Black Mask circulation peaked while the magazine was running the serialization of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (September 1929-January 1930), arguably his “artiest” novel. And issues containing previous Hammett serials—especially his first novel Red Harvest (serialized November 1927-February 1928)—also saw higher circulation than the issues around them. But the correlation between the publication of Hammett’s serials and high Black Mask circulation was only part of the story.

Black Mask circulation, 1925-1940, with issues containing the serialization of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon highlighted.

A closer look at the general circulation patterns reveals a couple of things: magazine circulation was typically higher in the winter than in the summer. In fact, this pattern is repeated across nearly every magazine title in the early twentieth century. Presumably, periodical readers were more likely to spend money on magazines in colder months when they were stuck inside. So, the presence of Hammett certainly didn’t suppress circulation, as Gardner surmised, but his presence alone may not have boosted circulation quite as much as the data suggest. Editor Joseph T. Shaw typically ran Hammett serials in the winter; was this choice tied to the fact that the magazine had a better chance of reaching occasional or crossover readers in colder months, while it needed to play to its core audience in the summer?

The rationale behind editorial choices remains difficult to determine, but these kinds of questions can resonate quite far in our understanding of periodical history and inspire us to ponder why certain pieces appeared at a particular time of the year. The only writer who rivaled Hammett in the pages of Black Mask was Carroll John Daly, a writer much preferred by Gardner because his work was more definitively “pulp.”[3] Daly’s serialized novels appeared during lower-circulation months in the summers. Were these designed to retain a core readership in the leaner summer months?

Of course, The Maltese Falcon also had the benefit of appearing at the first great peak of pulp circulation, just before the onset of the Great Depression; for many older pulp titles, this moment was also their circulation peak. The dataset for Black Mask (and other magazines) raises these and many other questions and avenues for further research: like a Hammett novel, mysteries upon mysteries.

Brooks E. Hefner is associate professor of English at James Madison University and is the co-director of Circulating American Magazines.

[1] Philip Cody to Erle Stanley Gardner, 8 July 1930, Erle Stanley Gardner Papers, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

[2] David M. Earle, Re-covering Modernism: Pulps, Paperbacks, and the Prejudice of Form (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 61, 63.

[3] Gardner credits Daly with inventing the hard-boiled style in “The Case of the Early Beginning,” in The Art of the Mystery Story: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Howard Haycraft (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946), 203-207; and “Getting Away With Murder,” The Atlantic, January 1965, 72-75.