Embrace the DH Cycle: Solve Problems, Create New Problems, Get Help, Repeat

But each of those workshops highlighted the difficulty of working with historic maps that were either on microfilm, housed in the county library’s vault, or reprinted on very large paper. Those formats were neither easy to work with in the field, nor easy to collaborate around in class. Each workshop also highlighted the ephemeral nature of community engagement that essentially ended with the conclusion of the walking tour. So, I began looking for ways to solve these problems, which lead me down a path toward DH.

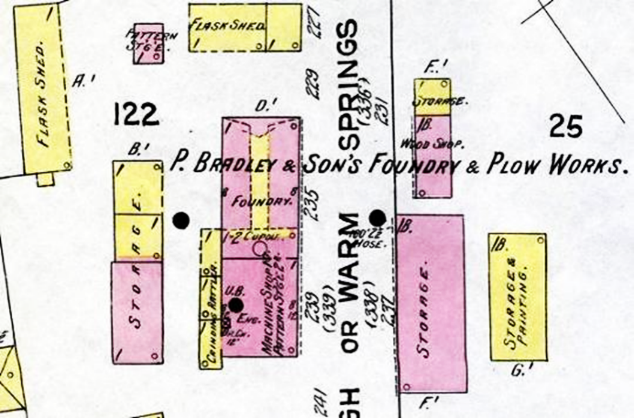

Our public walking tour rounds the corner of the machine shop of the P. Bradley & Sons Foundry, the center building in the 1912 map detail above.

Becoming Geospatial

Then when a geologist colleague offered a summer workshop on more advanced uses of Google Earth Pro, I believed I had found a way to avoid the complications of ArcGIS. I could import my map pages as image overlays and position them over modern satellite imagery. And if I could do that, I could use them in the classroom and even share them publicly. I saw in Google Earth a tool to solve my classroom map-use problem and my ephemerality-of-walking-tours problem. However, as I dove in I realized I needed to first work in Photoshop to edit the map pages, trimming the excess white borders where the map images would join into a mosaic of the whole. The DH cycle was beginning: the solution of Google Earth, led to the new problem of editing digital images. So, I got help with Photoshop from a colleague in the School of Media Arts and Design.

Repeat!

Going Public

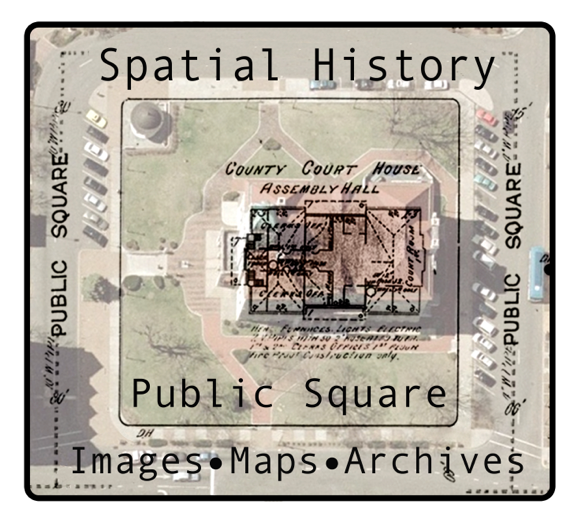

Thus began the third phase of my project, during which I named it, “Spatial History in the Public Square.” I wanted to make a custom geospatial interface that foregrounded the zooming, fading, and location pop-up markers. And I wanted the navigation bounded by the extent of the given map project, so that users could not get lost in the Pacific Ocean by accidentally scrolling the mouse too quickly. And I wanted to make it free to the public. Some well-known online spatial history projects were making impressive use of GIS and mapping programs. Yet as models, they were far too expensive and complicated for smaller, community-based institutions to duplicate and maintain. The time was right to bring these tools and methods within reach of communities with modest resources, to bring Spatial History into the Public Square.

I knew by this point that I needed more than collegial help to go any further. I needed to pay my collaborator so that s/he could focus on the project. I applied for and won a $4,000 Virginia Foundation for the Humanities Open Grant, which allowed me to recruit a recent graduate of our Geographic Sciences program to join the effort. Bradley had an eye for clean design and embraced the open source philosophy at the core of the SHPS vision. The result beautifully accomplished what I had envisioned and we presented it as a team at the 2016 National Council for Public History meeting in Baltimore and at local presentations in the community. Brad’s help solved the problem of Google Earth’s too-complex interface. Our presentations at the county library and the historical society confirmed our design choices, community members loved the simple, easy-to-use and understand interface.

Repeat!

Four Lessons for Doing DH at JMU

- DH projects often fall ambiguously between teaching and research, so the DH practitioner should be prepared to explain a project in terms appropriate to each realm. This was particularly problematic in the past. As my project evolved from merely wanting to view scanned map images in the classroom, to wanting to create and maintain a historical map project for the Harrisonburg community, I moved beyond the mission and expertise of instruction-oriented campus tech support. I was not creating an online course. I was not using clickers-in-the classroom. I was not requesting a WordPress site for a course. Today the dual teaching/research nature of DH at JMU is less problematic, largely due to the reorganization within the Library that replaced CIT with Innovation Services, and the soon-to-open Geospatial Commons in the College of Integrated Science and Technology. The environment for DH at JMU is supportive, but DH practitioners will still need to explain their projects ambidextrously.

- DH Practitioners will experience periods of difficult-to-measure productivity. Long and often steep learning curves in DH are difficult to sustain in the face of other demands and pressures. What you are learning is new to you and often requires significant time and attention. But, this stage does not produce new scholarship or research that can be published in one’s traditional academic field. Instead it takes time away from conventional research and publishing. Thus, DH remains risky for non-tenured faculty, who should seek clear administrative support in their home department in advance.

- DH depends on collaboration. There is no other way. Lone scholars do not succeed in DH. You cannot become proficient in each of the digital tools that will best suit your project’s goals. Digital tools change constantly, incessantly. ArcGIS went through a half-dozen versions in the time that I was rubber-sheet my map images. One must have collaborators who know the tools well.

- Collaboration is not free. DH projects are often born of collegial generosity, but they cannot mature in that space. Everyone at JMU is busy, as they should be. Small DH projects or early-phase work can be supported by small grants from various sources on campus. But sustained development of DH a project requires compensated collaborators. So, DH practitioners should develop grant-writing skills for external programs beyond the traditional, lone scholar humanities grants. And, as the Library’s Innovation Services department grows and the East Campus Geo-Commons opens, DH practitioners may find additional talented staff with dedicated time for collaboration on projects that are ready to grow beyond the germinal stage.

Endnotes

[1] See Kevin Borg, “Teaching with Historic Places: Sanborn Maps and Dusty Old Buildings” Notes on Virginia, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, number 52 (2008) pp. 40-46. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/Notes_On_Virginia_08.FINAL.Web.pdf

[2] Clear, brief overviews of the spatial turn in history include Richard White, “What is Spatial History?” Spatial History Lab: working paper, Stanford University, 1 February 2010 (https://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/pub.php?id=29 ); and Edward L. Ayers, “Mapping Time” in Geohumanities: Art, History, Text at the Edge of Place, eds., Michael Dear, et al., (Routledge 2011), 215-225.