Interview with Sharew Kelkile

Introduction

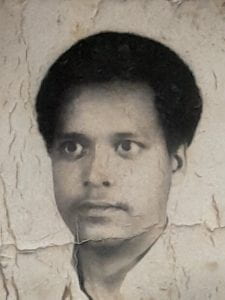

On November 22nd of 2023, I had the honor and privilege to have the opportunity to interview my father, Sharew Kelkile, and bring light to the experiences he faced during his immigration process. He used to tell my older sister and I stories from his past and the hardships he had to face. I remember feeling so much remorse for all the struggles he was forced to confront. Though, through it all his playful and lighthearted demeanor never faltered, which is something I have always admired about him. It is truly inspiring to hear about all the experiences forced upon him and hearing how easily he allowed them to roll off his back in comparison. I never thought that I would ever get the chance to actually sit down with him and get his story known by those outside our family walls. So, naturally, I decided on interviewing my father for this assignment, and it was truly an experience that I will treasure forever.

Early Life

Even as a child he held a loving and carefree personality. He was raised in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, by his single mother whom he loved very dearly. His mother was a prominent figure in his upbringing and life in general. She raised him into the kind, caring person he is today. When he attended school back in Ethiopia, he would get into trouble with the government due to the activism he expressed. He would protest any chance he would be given, not letting the fear of exile hold him back. Through these actions he found himself more and more of a target for the government. Though, this never stopped him. It was only when his mother warned him that he found the strength in himself to resist going. His mother had told him of a prophetic nightmare that she had that showed his path to demise. She knew that if he had gone back to school to protest he would be taken away for good, so she begged him to stay back and he listened. Many of his friends and peers were killed due to their publicly fearless acts of activism.

Many of these exiled students came together to form a group that informally went by the name of Ihapa. More formally, this group was known as EPRP, which stood for Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party. My father was a part of this organization, and when they were brought in for questioning he luckily slipped through the cracks and no evidence could be put up against him. While he was lucky to escape, many of the young activists he worked with were not. Affiliation with this group formed a ceaseless target on his back, one which only displacement could fix.

Migration

He left his homeland in Ethiopia when he was 28 years old. When he left, he did not inform anyone of his departure. This abrupt migration was due to the activism he expressed against the government, which at the time was imperially ruled by the Derg regime. His outward activism made him a prominent target for the government. It reached a point where he and a few of his friends were taken in and tortured in an attempt to force them into submission. Through this experience he saw the true cost of his activism. The Derg regime made sure to send a message to these young people. They shaved a stripe down the center of their heads and would dunk and hold their heads under ice cold water in order to further push these young students into passivity. Additionally, when these tactics weren’t enough, they did not shy away from taking lives if it meant it gave them a better chance at silencing the people who objected to their way of ruling.

Crossing the border was the only way he could truly get away from the target put on his back by the government. His journey was one that had a life of its own in a way. After he left Ethiopia, he traveled through Kenya for six years before he finally ventured off to the United States. He entered Kenya through a shared city with Ethiopia, Moyale. Many fled by taking this trajectory of travel. Moyale was known for its refugee population which allowed people from Ethiopia to seek solace with a sense of safety from their neighboring government. From there he began his gruesome journey to Marsabit, Kenya. In the interview, he described the journey as “terrible.” The land was covered with burning hot desert sands and no sight of life for miles to come. All that could be seen was the sand and the blaring sky. Marsabit lies right outside the barriers of the Chalbi desert. The journey from Moyale to Marsabit paved through the heart of the desert. He prayed in hopes of a miracle from God to give him the strength to go through with this journey. When recalling the moment, he expressed how he had this epiphany of hopelessness. He said to himself, “Oh my God, just God save me, save my life.” He explained that this venture made him rethink his decision of leaving. Yet, through this hopelessness he continued to persist on his journey to Marsabit.

After staying in Marsabit for a bit he decided to venture off to a refugee camp in Thika, Kenya. The refugee camp in Thika sheltered a diverse community of refugees. He recalled meeting people from Tanzania, Uganda, Zaire, Burundi, and Rwanda during his stay at this camp. This journey to Thika was not one that he faced alone. Not only was the desert air suffocating the lungs of the travelers, but the group he was traveling alongside also faced physical roadblocks in their journey. When my dad and this group set off to Thika, they were traveling by a matatu. A matatu is a van-like vehicle that can hold around 20 individuals. Shortly after the group set out on the venture, they were hit by an oncoming truck and ran off the road, rolling into a ditch. Many of the individuals that were in this vehicle sustained injuries and were visibly hurt from the crash. Though, my father came out of the encounter barely injured. While this group attempted to recover they unanimously decided on continuing the journey to Thika, even through the pain endured from the accident. They didn’t want to risk losing their chance, seeing that they already had all their needed documents on their persons.

Once they got to Thika, he stayed at the refugee camp for a bit. However, he quickly realized that he wanted to venture off to Nairobi, where he wouldn’t feel as confined. He stayed in Nairobi for the remainder of his time in Kenya. He described it as very diverse and he was able to make a life for himself there. At a certain point he was even asked to join his friend’s developing business, but he turned them down.

He knew that Kenya was not his end goal. He hoped to finally settle in the United States, where he could more freely make a name for himself. He knew that if he chose to go to the United States, he would have more opportunities available for him in all aspects of livelihood. Though, he was also given the option to immigrate to Australia or Canada. A few of his acquaintances at the time had warned him about the racism endured in Australia, so naturally he strayed away from this option. As for Canada, he had gone back to Moyale to help and guide one of his cousins through the gruesome journey through Kenya. So, he ended up missing the Embassy’s visit, which only happened once every six or so months. Though, overall he was pretty set on the United States as his first choice of residence, so this hurdle quickly rolled off his back.

Integration

In 1989, he arrived in the United States after years of tumultuous traveling. He landed in New York, the city where dreams are made reality. From there, he was quickly transferred onto another flight to Georgia, where he met his sponsor, Ron Smith. He was not aware that he would be meeting up with a sponsor. The immigration services that he kept in contact with only told him that the Bridge Refugee Services was sponsoring his immigration. He was completely uninformed on the fact that he would be getting picked up by a sponsor, as well as then moving in with him and his family. He was to stay for however long it would take him to gain footing in this new environment. Though, Sharew only stayed with the Smiths for three months. He quickly got a job as a security guard two weeks after arriving in the country.

However, when searching for an apartment of his own he was faced with a few hurdles. Finding an apartment was no issue for him, sadly it was the color of his skin that hindered his housing options. In the interview he recalled this moment, he explained that he had found an ad on rentals and quickly got in contact with the woman who posted it. This woman and him planned on his visit, and it was made clear that the apartment was available for him to rent. Though, when he arrived he was immediately shut down and told that the apartment was already sold. On his way over there, he asked a girl for directions and once she saw the address that he had written down she looked confused and asked if he was sure it was the right address, alluding to him being turned away upon arrival.

Even through all this strife, he was finally able to get an apartment in Collegedale, Tennessee. Where he then attended Chattanooga State Community College for Mechanical Engineering. Additionally, he was able to buy his first car and paid in full with cash. During his time in Tennessee, it was noted that discriminatory microaggressions were something he faced and eventually got used to. Though, he enjoyed his time receiving an education, and claimed that this notion of racism was not as evident at his school.

A year later, a newspaper article was written about him by a man named Tony Thedford. This article was titled, ‘Kelkile, refugee from Ethiopia, finds success in Collegedale’. Thedford interviewed Ron Smith and his wife, Jeanie. Through this he was able to see what life was like living with Sharew. Ron and his wife joyfully expressed the amount of ease they felt while living with him. During the interview Smith voiced that, “For us it has been rewarding spiritually and educationally. We are glad to be able to share what we have and learn a few things about his culture.” Furthermore, Jeanie Smith added that, “Sharew is a regular part of the family. He didn’t disrupt our lives in any way. He is a very special friend.” It was truly touching to look back at what his sponsors had to say about his stay with them.

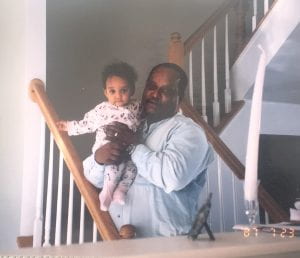

It wasn’t until he decided to visit D.C. that he realized how community deprived he felt in Tennessee. Once he reached the capital, he never looked back. The diversity in the city allowed him to easily find his immigrant community. From there, he made a new life for himself. He was able to make friends with those who shared the same struggles and experiences as him. He worked at J.W. Marriott for some time, but eventually quit due to the seasonality of the job. He later started work as a Limosine driver and became well off through this occupation. After we moved to Virginia, he became my sister and I’s school bus driver, and has been working with PWCS for over sixteen years.

Membership

My father, Sharew Kelkile, identifies himself as a U.S. citizen. Though, this does not take away from his strong identity as a proud Ethiopian. He holds his homeland dear to his heart. However, he has not been back since he left. Once he left, he knew that he’d probably never be able to revisit his homeland due to the circumstances of his departure. It’s been forty years since he last saw his homeland. Upon arrival in the states he would frequently send money back to his family at home. This continued on for many years, until his mother sadly passed and family back at home became scarce. Through it all he has come to terms with his life in the United States. He is always quick to show gratitude for what he has been given through this tumultuous journey, a family which he holds dear to his heart.

Conclusion

It was truly eye opening for me to have the opportunity to educationally facilitate and record this heartfelt conversation with him. Through his long and grueling journey he was able to find a place he could call home. Even though he was faced with strife and discrimination at times, he never let it falter his lighthearted and loving nature. He has always been my inspiration growing up, so to be able to have his story heard is something that I will always remember. Taking this class has allowed me to gain more experiences in the world of immigration and this project made it so I could connect through the experiences of one of my dearest family members, my dad.

Bethel Sharew 00:02

My name is Bethel Sharew and I will be interviewing my dad, Sharew Kelkile, who has immigrated from Ethiopia. Just to start

us off, how long have you been in the US?

Sharew Kelkile 00:20

Since 1989.

Bethel Sharew 00:20

Mm-hmm. And when were you born?

Sharew Kelkile 00:29

1956.

Bethel Sharew 00:30

Alright, so you’re 67 years old?

Sharew Kelkile 00:34

Yeah.

Bethel Sharew 00:34

Right. And where did you grow up?

Sharew Kelkile 00:37

Addis Ababa our capital city.

Bethel Sharew 00:37

And who raised you?

Sharew Kelkile 00:37

My mom.

Bethel Sharew 00:37

And she was a single mother, right?

Sharew Kelkile 00:37

Yes. She was a wonderful mother.

Bethel Sharew 00:37

Mm-hmm. And how did your family react when you left?

Sharew Kelkile 00:59

Oh it was terrible, they didn’t know until I just reached Nairobi, you know, a couple of months, you know. I didn’t tell them

when I just ran away.

Bethel Sharew 01:12

And was there any reason why you had to leave so abruptly?

Sharew Kelkile 01:19

It was because of politics.

Sharew Kelkile 01:22

From the beginning, you know, the government arrested me so many times, two or three times, they tortured me. And then

after that, when I just came out from the prison, I just, I used to work in the government office.

Sharew Kelkile 01:44

And then every time, you know, original autonomy, they would tell us to teach the people, you know, who is working with us

together. And then every time they would watch us, if we just cross to the another thing you know they just call Ihapa.

Bethel Sharew 02:04

Ihapa?

Sharew Kelkile 02:04

Yeah, it’s a political organization.

Bethel Sharew 02:04

How do you spell that?

Sharew Kelkile 02:04

Ihapa? Ethiopian– the abbreviation I can’t remember you know.

Bethel Sharew 02:04

But through that organization

Sharew Kelkile 02:04

Yeah, they just suspended us.

Sharew Kelkile 03:00

They didn’t find any evidence, you know. I just participated in that political organization. I didn’t, they didn’t find any

document. So they just released me. And then every time they were watching me, what’s going on, what are you gonna do?

Sharew Kelkile 03:25

You know, because of that, there’s too many, too much pressure.

Bethel Sharew 03:30

And was it- it was due to your activism that they targeted you?

Sharew Kelkile 03:38

Yeah.

Bethel Sharew 03:38

Right.

Sharew Kelkile 03:39

So because of that, I just didn’t feel comfort.

Bethel Sharew 03:42

Yeah.

Sharew Kelkile 03:43

So if I just stay, they might just take me again to, they will arrest me.

Bethel Sharew 03:52

And when was the last time you have been to Ethiopia?

Sharew Kelkile 04:01

Since I just, I just left in 1984, since that, I used to work in government office and then I just ran away through the border,

when I work, you know, public rental housing department, I used to work there.

Sharew Kelkile 04:35

So I just ran away through the border, was the Moyale.

Bethel Sharew 04:42

And that’s like the border between Ethiopia and Kenya?

Sharew Kelkile 04:46

Ethiopia and Kenya, yeah.

Bethel Sharew 04:48

Okay.

Sharew Kelkile 04:48

There is Ethiopia Moyale and there is Kenya Moyale.

Bethel Sharew 04:54

Right.

Sharew Kelkile 04:55

So immediately I just ran away to Kenya, Moyale police station and then I just gave my hand to the police.

Bethel Sharew 05:07

How old were you when you left?

Sharew Kelkile 05:11

Around 28 I think.

Bethel Sharew 05:13

Wow.

Sharew Kelkile 05:14

28 years old.

Bethel Sharew 05:19

And what did your journey look like?

Sharew Kelkile 05:23

It was terrible. It looks like from Moyale, Kenya to Marsabit. It looks like a desert. There is no tree. It’s burning sand. It’s dark.

You will see- from land to- you will see the sky. You know, land and sky. There is no tree.

Sharew Kelkile 05:52

There is nothing. It’s a desert. Since we just to reach to Marsabit, then very hot, you know, Sahara desert. That is the one. In

my mind, why I just left my land? To see this thing? Oh my God, just God save me, save my life.

Sharew Kelkile 06:26

I just, when I see those things, and then when I just went to the Marsabit, I’m okay. Then I just went to police station, and

then the police station, you know, the officer, he’s nice. And after he just would take my document and everything, he just

advised me, you can relax in the town, you can go there, and then there is a shopping center, whatever you like.

Sharew Kelkile 07:05

You’ll just enjoy there, and then come back, whatever you like, if you want, you can stay there, he said. Okay, I just stay

with, I found my cousin, you know. I just stay there, and then enjoy, and then at that time, I used to smoke cigarette.

Bethel Sharew 07:29

Right.

Sharew Kelkile 07:29

Yeah and the Winston, it’s very strong. I used to smoke that cigarette, and then, but I just quit after that. When I see that

it’s a different kind of cigarette. I say, forget it. I don’t know why I- I can quit.

Sharew Kelkile 07:51

I quit. I don’t smoke. And then I came back in the morning, he told me he’ll help us for a couple of days. Then when the

transport is ready, he’ll go with the paper, he got all my papers ready. Then we just get a Somali driver.

Sharew Kelkile 08:21

I think three or four guys get together, two ladies I think. Then we just start to roll from Marsabit to Nairobi Thika, but in the

middle of the road, joining, a heavy truck comes and crashes into us and we just roll over into ditch.

Sharew Kelkile 08:55

You know, then I’m okay, I sat back, and the others, they’re bleeding, the girls also just hit their head. And then some of

them, they’re bleeding. It’s not that much heavy, but they treat them, and then we start to get another car.

Bethel Sharew 09:27

So they kept going?

Sharew Kelkile 09:28

Yeah, keep going. We can’t stay there, you know, because we have our paper and everything we don’t want to mess. We

just hold our document, you know. And then we just get the matatu, they call it.

Sharew Kelkile 09:43

It looks like it will hold around 18 people. They call it matatu.

Bethel Sharew 09:56

Like a vehicle?

Sharew Kelkile 09:58

It looks like a station wag- or, I mean a big van. Oh, okay. We went there, then they took us to Thika. We went there, the

refugee camp.

Sharew Kelkile 10:17

We stayed a couple of months, I think. They, you know, immigration, they will come from Nairobi to Thika to interview us.

Then to get information from us. If they just accept, they will accept. If they just regret, they will regret, they will

automatically, they will take you to different, I mean, deport.

Sharew Kelkile 10:53

Some of them… they, you know, pending, pending means they will search- they will reexamining in another days to know in

detail about your case, you know. I’m okay, immediately I passed. Then after I pass, you know, every time I’ll go to Nairobi

and come back to the camp. I will stay a couple of days and come back to Thika.

Sharew Kelkile 11:48

Then after I finish, I just went to Nairobi.

Bethel Sharew 11:52

And Thika is the refugee camp?

Sharew Kelkile 11:54

Thika is very far, very far refugee camp. You know, the camp looks like a little house. Then to live around that area, it’s just

too hard.

Bethel Sharew 12:12

There were refugees from all over?

Sharew Kelkile 12:16

Refugee from Tanzania, Uganda, Zaire, Burundi, Rwanda, different places. We just get together. Then we’ll sleep, you know,

top and- you know, up and down.

Bethel Sharew 12:35

Oh, like bunk beds?

Sharew Kelkile 12:36

Yeah, just like school, you know, college school. Right. Dormitory. And then we just sleep like that. Then one time, the funny

thing, they would give us, you know, most of the Uganda, Zaire, Kenya, Tanzania, those people, they would eat wild banana.

Sharew Kelkile 13:03

The way they teach us, the way they teach us how they just make it. Right. One day, that’s my turn. The funny thing. I just

cook, they would give us meat and different things, onion and everything. I just make sauce very nice.

Sharew Kelkile 13:26

But the Matoke, they call it Matoke, means banana, wild banana. Banana. Wild bananas.

Bethel Sharew 13:37

Wild bananas.

Sharew Kelkile 13:38

Yeah. So I just peel that thing and then cook it, cook it the whole thing. And then when it just well cooked, you’ll…

Sharew Kelkile 13:52

smash it and it looks like Ugali, just like Ugali, the Kenyan favorite food now. Matoke, that’s Uganda and then Zaire, those

people they will eat Matoke. So I just do Matoke in the round bowl plate and then I put Matoke inside in that bowl and then I

just open the middle one and put the sauce and then cover it and I put in their bed area you know they’re not around that

area. They are- they gone, they will come back after three or four hours. When they come back, they told me “which kind of

food do you cook?” “Matoke.”

Sharew Kelkile 14:56

“When did you cook?” They said, they know it, you know. “I don’t know.” I said, “four hours ago?” “What?” Four hours ago

when they’re just getting that food? The sauce is okay, but Matoke is just hammer. It’s stone.

Bethel Sharew 15:16

Oh. (laugh)

Sharew Kelkile 15:21

They were throwing it. I don’t know at that time which kind of food. When I just tasted it, I tried to just break it. You can’t

break it. You can’t- very strong. Very strong. I said, “okay, I’m sorry.”

Sharew Kelkile 15:44

“I didn’t know. I just did what you do. I just watched you, the way you did it.” “I know you did it good, but the only thing it

cannot stay at least 10, 15 minutes.”

Bethel Sharew 16:02

Oh.

Sharew Kelkile 16:02

And then after that, if it just stays for long.

Sharew Kelkile 16:07

That’s it. Yeah. I said, “I’m sorry. I just found Matoke, banana, wild banana from our girls.” I just asked them to give me, I will

replace it when they just come and get it. They gave me the whole bananas.

Sharew Kelkile 16:31

Then I just give it to them and they cook it. Right, the whole bunch. The whole bunch, they cook it and they eat it. And the

funny thing which I just see it, you know, it was funny.

Bethel Sharew 16:48

Yeah.

Sharew Kelkile 16:49

So I just went to…

Sharew Kelkile 16:52

After that I just went to Nairobi for good. I’m not coming back.

Bethel Sharew 16:59

Mm-hm.

Sharew Kelkile 17:00

Then I stayed in Nairobi. It was the city of Eastleigh. They called it Eastleigh. That area, the Somalian, Somalian, there’s

different people they just live together.

Sharew Kelkile 17:24

We stayed there. Everything is good. In the morning we’ll go to the UNHCR to see what’s going on. To check out if there is

anything, you know, available. They tried to just, they told me, they just asked me to apply to borrow money and make

business, you know.

Sharew Kelkile 18:04

I said, no, I don’t want to just make business here. I just want to just go.

Bethel Sharew 18:10

Mm-hmm.

Sharew Kelkile 18:11

I don’t want to stay here. If I stay here, that’s it, I’m not going nowhere and then I just have to struggle, hustle, you know, to

make business.

Sharew Kelkile 18:25

No, I don’t want to. (unintelligible) No. I just refused. When until, you know, the embassy comes in there is no embassy, it’s a

counselor. I just almost stayed for six years. Then after that, I just processed it with the- You know, the problem, once in six

months, they will come from United States, the state, you know, the counselor to make an interview.

Sharew Kelkile 19:09

Then when they just left, they have to come back another six months, you know. You have to just stay until they come. Then

after we just finished the process, they accepted my case. They just accepted everything and to just make arrangements to

fly, it takes another six or seven months.

Sharew Kelkile 19:47

And then finally I just get it. I just went to New York and the domestic flight to after New York I went to Atlanta and then I just

get my sponsor they didn’t mention it they didn’t tell me. They just told me “the World Church is sponsoring you” but they

didn’t mentioned is I know we just write each other letters or something with the Ron Smith.

Bethel Sharew 20:30

Your sponsor.

Sharew Kelkile 20:32

Yeah, but they didn’t tell me he’s the one. When I just went to Atlanta “my name is Ron” (unintelligible) who is he? “I’m sorry

they didn’t tell me they didn’t inform me. They told me only the World Church will sponsor you They didn’t give me your

name. I just was surprised when I see you.” And then he just talked to them.

Sharew Kelkile 21:11

“Yeah, we didn’t tell him.” They told him the truth. “We didn’t tell him. We just-“

Bethel Sharew 21:18

Sorry, do you know why they didn’t tell you?

Sharew Kelkile 21:21

I don’t I don’t know I don’t know why they didn’t tell me. They were supposed to tell me from the beginning, you know, we

write letters every time we have good communication, you know every time. Finally anyway, it’s good. Then we are the- he

just made sure he just ask them. “That’s that we didn’t tell him. We told him the Refugee World Church accepted his letter

and then he just comes through that.” It’s okay, but those people Ron and his wife and he has a young daughter she’s nice,

and they are very nice for me.

Bethel Sharew 21:48

And I, I know that there was an article written about you. Lets see, by Tony Thedford?

Sharew Kelkile 21:48

Mm -hmm.

Sharew Kelkile 21:48

And it’s titled ‘Kelkile, refugee from Ethiopia, finds success in Collegedale’ and I just I was reading through it and I thought

like the quotes from Smith and his wife, were just very touching and shows a lot about how your experience was living with

Powered by Notta.ai

them.

Bethel Sharew 23:03

And I’d just like to like maybe read that. He says, “for us, it has been rewarding spiritually and educationally. We are glad to

be able to share what we have learned. And learn more things about his culture.

Bethel Sharew 23:26

And Sharew is a regular part of the family. He didn’t disrupt our lives in any way. He’s a very special friend.” I don’t know, I

thought there was a very sweet.

Sharew Kelkile 23:44

Yeah, very nice. And I love them.

Bethel Sharew 23:46

Shows how much of like a family you guys formed?

Sharew Kelkile 23:48

Immediately I didn’t feel anything. I just see them just like a part of my family. We love each other. They are very nice. And

then he just recommended me to just take a college, you know. “Immediately you don’t have to just stay for long.

Sharew Kelkile 24:11

Just take the exam, entrance exam, and then see what you get. If you just get it, then immediately you will start.” And then I

just went there. Successfully, immediately the guy, the one which he just examined me, you know, he is really glad.

Sharew Kelkile 24:37

Immediately he told him “he was successful and very nice. Immediately he can start,” he said. Immediately I just started.

Then I just started mechanical engineering. It was nice. My goodness, I have interest you know at that time.

Sharew Kelkile 25:01

I was 28, you know. I don’t have any, you know, right now I’m getting old, you know. Everything is not the same just like

when I was 28.

Bethel Sharew 25:19

I mean you were around like 33, 34 at that time?

Sharew Kelkile 25:28

No, 33, 33.

Bethel Sharew 25:30

Six years in Kenya?

Sharew Kelkile 25:32

Yeah, six years, yeah, 33, 34.

Bethel Sharew 25:35

So when you first arrived to the US, you were about 33, 34?

Sharew Kelkile 25:39

33, yeah around 33, 34. Yeah.

Bethel Sharew 25:42

They were encouraging for like education and all that?

Sharew Kelkile 25:47

Yeah, I didn’t forget the one which I just take the class when I was back home.

Sharew Kelkile 25:54

I have, you know, mathematics are very nice. We’ll struggle by ourselves. We don’t know calculator, we don’t know- just our

mind is very sharp at that time. You know, now you know you have to calculate for everything for little thing.

Sharew Kelkile 26:20

At that time, immediately will respond. When they just ask me, you know, the question, immediately I will figure out, I can

calculate and I don’t have- I don’t need any calculator or something. So, I started very nice.

Sharew Kelkile 26:52

Then I started to just apply different places. I just get a security job in Georgia. When I applied to Georgia, they just

accepted. Then everything straight, I started to find an apartment. One time, the apartment, when I just, you know on the

newspaper, you’ll find it.

Sharew Kelkile 27:40

Then I found one place. I just called, picked up the phone and talked to her. She said, “Come here. You can come and see

the room which I have.” I just drove towards her house. Then a little town, I just went there. I talked to one of the girls.

Sharew Kelkile 28:14

She is a student at Chattanooga University. I talked to her. I said, “can you just help me out? The address, I just missed the

address.” She said, “where are you going?” “I just went to- I’m looking at the house to rent.” Then, “are you sure?” she said.

“yes, I am quite sure.”

Sharew Kelkile 28:43

“Okay.” You know, kindly I am you know- I didn’t feel anything. So, “tell me when you come back, let me know,” she said.

“Okay.” I just went there. When I just reached the place where her house, and I called her, and she just came out from the

house, when she looked at me, she said, “I’m sorry, it’s already rented.”

Sharew Kelkile 29:18

She said. “Oh, I’m sorry, why don’t you tell me from the beginning before I just come here.” And she said, “sorry, it’s already

rented.” I just go back to the place where, I mean, the other girl who just give me that address where I’m looking.

Sharew Kelkile 29:46

Then, “what did you get?”, she said.” Oh my God, the lady, she said, it’s already rented, she said,” She’s laughing. “That’s

why I just told you, when you come back, just let me know. The one which I say is, I know the area.”

Sharew Kelkile 30:09

She said. I didn’t put in my mind, you know. And then I just went to Chattanooga, this apartment, you know, to find one, you

know, efficiently. And then I just talked to one of the person, the owner of the building.

Sharew Kelkile 30:36

Then when I just talked to him, he said, “where you from, originally?” “Yeah, I’m from Ethiopia,” I said, “Oh, you Ethiopian

people, they are innocent, so don’t worry, just- I will take care of you.” He just gave me furnished.

Sharew Kelkile 30:55

Yeah, everything, everything furnished. It’s very cheap, the rent. Then I started to live there, and then drive to Georgia. So

I’m okay. Then go to the class, I start. Then after that, I just stay for one year, come to Washington DC to visit when school

closed.

Sharew Kelkile 31:28

I say, let me stay here, little bit. I just- let me help my family, my mom, she’s getting old, you know. I have to just help her a

little bit. And then before you know, you never know, you know, if I just didn’t, you know, help her right now, you know, the

age is getting, you know, time to time she is getting old.

Sharew Kelkile 32:00

So I just work to J .W. Marriott Hotel, as a bartender. And then I just, you know, to tell you the truth, I can get tips and I got

money. Then at that time, you see, I will send it to them, a couple of money.

Sharew Kelkile 32:25

And then when I just wait six months, the money is coming, but after six months, three months, very slow. There’s no

business. And then at that time, you know, the money is shrink. And so because of that, you know up and down, up and

down.

Sharew Kelkile 32:49

Let me do next year and then, let me do next year and then after that I didn’t go back to this place.

Bethel Sharew 32:57

Oh, was it like seasonal?

Sharew Kelkile 32:59

Seasonal, you know, seasonal. You know, when you work hard, six months, there is a tip and everything.

Sharew Kelkile 33:07

It’s good payment, but three months, there is nothing. There is an apartment rent and there is also, they will, you know,

watch me, you know, how he, he said, he started to send money and then they, they are waiting, you know, couple of

months.

Bethel Sharew 33:31

Right.

Sharew Kelkile 33:32

So after, because of that, you know, I just stick in DC almost 13 years. In DC, I live 13 years. Then after that, you know, I just

get you.

Bethel Sharew 33:48

I was born in DC.

Sharew Kelkile 33:51

Yes. And then you didn’t stay for long.

Bethel Sharew 33:54

Oh, yeah. Six months?

Sharew Kelkile 33:54

Yeah, six months or something. And then I just get Mahlet and then I used to drive the limousine, you know, business. It was

nice. And then, you know, one time something has happened to me.

Sharew Kelkile 34:14

And when I just drive around 3′ o’clock in the morning, when I just come from downtown towards Military Road, you know,

gangsters, they just follow me by car. I’m driving my limo and then my limo is, you know, oh, he just come from work and he

has money.

Sharew Kelkile 34:41

Yes, I have a couple of hundred. And then when I just come to, in between my house to- it’s not that much close, and they

just follow me. When I just drive fast, they will drive fast. When I just slow, they will slow.

Sharew Kelkile 35:05

And then when I see one car in front of me, he’s over there. His engine is running, he’s inside. But I drive towards him, fastly,

immediately, I turn. And then they jump on him. They crash. (unintelligible)

Sharew Kelkile 35:30

Oh lord. I just pray to God. He saved me.

Bethel Sharew 35:37

Right, you got out of there.

Sharew Kelkile 35:37

I just went towards my house? Then I used to live in Rittenhouse. Then I just went to Rittenhouse. There is a police also the

police hide and then watches the situation the area. The area is no good. So I just park immediately. Then went to my house

and I’m successful. I just survived my- that situation you know was very very tough. If they get me they would kill, you know,

to get that money. So That’s it.

Sharew Kelkile 36:32

Then I just went to tell Messi. She said, “no we cannot stay here, we have to find another place. Virginia.” She said. “Okay, if

you say, we will go to Virginia.” We just buy a town house in Virginia. And then we start a lovely life, you know. You grow- I,

you know, I just get wonderful daughters, Mahlet and Bethel, and then you know I just prayed to God to give me wonderful

kids, and I pray to God if you give me I will come to visit your heart- your place Jerusalem. Just- I Just you know give you

know to God, if you give me I will come and visit. I just went to Jerusalem with you.

Sharew Kelkile 37:48

You’re very strong.

Bethel Sharew 37:49

I was like four.

Sharew Kelkile 37:50

The one, the mountain, you just climb just like a strong boy, you know, strong girl. Yeah, strong girl, my goodness. I can’t

believe it, you know, the other boy, our cousin, my cousin.

Sharew Kelkile 38:12

He just, he don’t want to come out. He stay with his father, you know, he don’t want to go all the way.

Bethel Sharew 38:20

Yeah, there’s a lot of walking.

Sharew Kelkile 38:21

A lot of walking, you know, he’s scared. He don’t want to just go that mountain, you know.

Bethel Sharew 38:29

Honestly, yeah.

Sharew Kelkile 38:30

Honestly, he didn’t. His father will stay with him because he don’t want to go. His wife and the other one, the youngest one,

he just went with us. So we just visit different places, you know, very nice blessing place.

Bethel Sharew 38:51

And I know we’ve been to Jerusalem, but have you been back to Ethiopia since you left?

Sharew Kelkile 39:01

No, never. Because of politics I can’t go there.

Bethel Sharew 39:04

Mm-hmm.

Sharew Kelkile 39:05

Because all the leaders they will come with gun, you know, they are armed to do whatever they like. If they don’t feel

comfort, they didn’t give you a chance.

Sharew Kelkile 39:21

We just demonstrate here about the leader. We don’t feel comfort, you know. After military, the Meles regime is coming,

Meles is the worst one. They create a problem, you know, they separate the land and tribalism.

Sharew Kelkile 39:46

And then the other one, the one which he comes after, he passed away, Meles. He is coming, he is the devil too. That’s it. A

lot of people die. A lot of people, he don’t care about the people. He care only the tree, you know.

Sharew Kelkile 40:05

He will grow the tree, he will build the building, you know, instead of helping the poor people or innocent people, they are

fighting in different places, you know. He just get the gun from Arabs and then they gave him, he will get that gun to kill the

innocent people, you know. But still now, a lot of people die, even the kids, you know.

Bethel Sharew 40:43

Yeah.

Sharew Kelkile 40:45

The kids, they are kids. You know what she said? I never forget. You know, “please, please, leave me. I don’t want to be

Amhara.” She said, “I don’t want to be Amhara from now.

Sharew Kelkile 41:03

Just don’t kill me.” They kill her. Can you imagine? She is five years old. Can you imagine? A lot of kids pass away. A lot of

innocent women, you know, they pass away. Because of the situation, you know, that place is terrible.

Bethel Sharew 41:29

And I know when you left Ethiopia, you didn’t leave alone. You were accompanied with your cousin, Roman, right? And… And

she didn’t end up going to the US, did she? She went to Canada?

Sharew Kelkile 41:51

No, she just- I just get her from Moyale, and then when we come back to Marsabit, and she processed it to Nairobi. And then

after that, they accepted her case. And then I took her to the United States Embassy.

Sharew Kelkile 42:21

And she processed it, and she passed everything. And then she came to the United States. And then after that, the one

which… right now, her husband, he lived in Canada. So he invited her. And then they married each other.

Sharew Kelkile 42:48

That’s because of her husband. She just stayed there.

Bethel Sharew 42:54

I didn’t know that.

Sharew Kelkile 42:55

But she just… as a refugee, she just… the American government accepted her case.

Bethel Sharew 43:00

Okay. And… Was it tough leaving?

Sharew Kelkile 43:22

No, it’s not tough. I love it, I love it. I’m successful because I have wonderful kids. I have everything, you are matured, you

are a third year right now, you will graduate next year. And then the Mahlet, she already finished, she graduated from

university, she’s successful and she’s working. And I’m proud of you, both of you, you and Mahlet.

Bethel Sharew 44:04

And was there any specific reason why you chose the US to immigrate to?

Sharew Kelkile 44:15

No, that’s, you know, I just get information from my other friend, you know. I have a friend from Australia, I have a friend

from Canada. The friend which they just informed me from Australia, they are very racist.

Sharew Kelkile 44:42

If you just come, we just get a hard time because they racist, they say. So why should I just go to get such kind of thing? I

don’t feel comfort, you know. When I just come here, I don’t have any problem.

Sharew Kelkile 45:02

I know if you know the people which they don’t comfort, it doesn’t matter, that’s their way.

Bethel Sharew 45:13

You can tell.

Sharew Kelkile 45:14

Yeah, I will figure out by their face.

Bethel Sharew 45:19

When you came to the US, did you experience discrimination other than the whole apartment ordeal?

Sharew Kelkile 45:32

No, because when I see, I just stick Washington DC. So when I see Washington DC, it looks like my capital city, Addis Ababa.

So I don’t have any discrimination in Washington DC. And then when I just come here, I don’t feel anything.

Sharew Kelkile 45:59

I just start the Prince William School. I’m successful. I just work 16 years. I just left DC. The Limo, doesn’t work. If I am here,

when they call me, within 10 -15 minutes, I have to be there, but the way which I just live is far away.

Sharew Kelkile 46:33

50 minutes drive from here to there. Washington DC is far away. So I just quit. Find another thing. Successfully I just get that

this job. I’m working hard and then you know, babysitter I didn’t pay anything.

Sharew Kelkile 46:58

I’m your babysitter, I’m the driver, you know, I will take you together. So we just survive everything you know. We don’t feel

anything.

Bethel Sharew 47:14

I mean, what about back in Tennessee and like going to school there? How was that experience? Did you face discrimination

there or?

Sharew Kelkile 47:31

Well, the only thing which I saw was in the neighborhood area. But in the school I don’t have any problem. The school is

good, very nice. It’s a city, you know.

Sharew Kelkile 47:48

It’s a nice city. But the one which I live is, you know, Bush area, you know. Bush area? Yeah, I mean, it looks like the country

side. So, in that area, you know, there is a farmer, there is a lot of things, you know.

Sharew Kelkile 48:09

You can tell when you see them, you know. You can read. Even, you know, let me tell you, the way which is, they can’t read,

they can’t write. They just do by finger.

Bethel Sharew 48:26

Fingerprint?

Sharew Kelkile 48:27

Yeah, fingerprint to sign.

Sharew Kelkile 48:30

No education.

Bethel Sharew 48:33

I’m glad you were able to get an education.

Sharew Kelkile 48:37

They don’t know, they don’t know. When I see them, I just, I used to work in a company. The one which I just work in the

company. Most of them, they can’t write.

Sharew Kelkile 48:54

They’re guessing, you know. When I saw, oh, I was like, American, is like this, the American people, they didn’t learn. They

don’t know how to write, they don’t know how to read. Oh my goodness, I say.

Sharew Kelkile 49:13

So now, I just figure out, I love DC area. The capital city, you know. All international people, you know, they get together.

And then I don’t have any feeling, you know. It looks like my capital city, Addis Ababa.

Sharew Kelkile 49:37

So I’m comfort. Even here also, Virginia. Yeah, the one which I just live in Prince William is nice.

Bethel Sharew 49:47

At least more diverse than Tennessee or Georgia.

Sharew Kelkile 49:51

I can’t figure out, I can’t say anything about that. You know, the Tennessee is a little…

Sharew Kelkile 49:59

Even you know, there is no tax. They didn’t cut tax when you work. Because the minimum wage is very low. They pay you,

really it’s not that much. Everything is good. Very nice. I enjoyed it.

Bethel Sharew 50:28

And would you want to go back to Ethiopia?

Sharew Kelkile 50:34

When there is a peace, if there is a peace I will go with you, not only myself. The family will go together, and then we will

visit my born place, we will visit different places, you know. So we will enjoy it.

Sharew Kelkile 50:59

When the government changes, a new government which is peaceful, plus who is thinking about the people, not thinking for

money.

Bethel Sharew 51:11

Yeah.

Sharew Kelkile 51:12

So if such kind of leaders come. I love it. I’d love to visit my homeland. My second land is America.

Sharew Kelkile 51:25

I love America. Because I’m successful. I’m okay. I’m surviving. So the first one, Ethiopia, if I just went to there, successfully,

the love of the people who, you know, they have culture. The American here also they have culture, lovely culture.

Sharew Kelkile 51:54

Ethiopia also, you see, the people of, you know, the farmer even, when he just invites you, if new people come to visit him,

he will wash his leg- their leg, their shoes, you know.

Bethel Sharew 52:12

Oh, the guests?

Sharew Kelkile 52:13

Yeah, the guests.

Sharew Kelkile 52:15

He will wash, and then he will give his bed, and he will sleep on the floor, you know. They are very kind. Very kind. But now

there is nothing such kind of things, you know. They, you know, the leaders, is thief even the the one which they just get

together with them is thief.

Sharew Kelkile 52:49

Everything we have gold, a lot of gold, we have a lot of mineral but they use it. I don’t know where they took the money, you

know the people they are poor still. Innocent people if they say something they will hang them.

Sharew Kelkile 53:14

If they say “the leader is not good,” “why you say that,” they will kill them. That’s it. —

Recent Comments