Faculty review of a student-produced minstrel show, “A Dark Night at the Normal”

The February 1920 issue of The Virginia Teacher features a faculty review of a student-produced minstrel show, “A Dark Night at the Normal.” Significantly, the next item describes a pageant hosted by the Lee Literary Society titled “The March of Democracy,” performed at the New Virginia Theater in downtown Harrisonburg the previous month. This performance was given “under the auspices of the Daughters of the Confederacy.”

One of the most direct opinions on racial discrimination during the school’s early years comes from a book review by faculty member Dr. John W. Wayland published in the February 1921 issue of The Virginia Teacher. Wayland reviews several books either by or about African Americans published within the past year, most notably W.E.B. DuBois’s autobiographical book, Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil (1920). Wayland’s tone in this review alternates between praise, rational coolness and pointedly opinionated. He notes of Dubois that, “If its author were not known to be a Negro, white people would read it as a sort of wonder book—a revelation in imagination and in the power of the English language” (33). On the other hand, Wayland complains that Dubois “perhaps asks for too much too quickly. He perhaps does not acknowledge enough the wonderful upward steps his race has taken in this country in fifty years. He perhaps is not duly optimistic over the fact that in America the whites have been losers and the blacks gainers” (34). The final half of the review considers “the Negro problem” more broadly, including recent race riots and the KKK. Wayland ends by calling for what is still essentially a so-called separate but equal system.

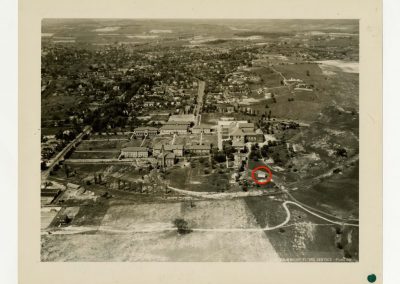

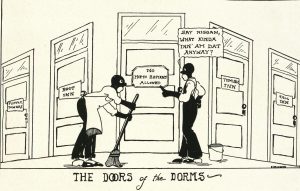

Bluestone 1966

Though the school was a segregated, highly gendered institution for roughly the first fifty years, there were two notable exceptions: black entertainers and black employees. The Breeze notes that on November 29, 1924, the “William’s Colored Singers,” an internationally renowned quartette of African American vocalists established by Charles P. Williams in 1904, gave a performance during chapel; additionally, the musical group was introduced by a “Rev. Austin,” pastor of  Harrisonburg’s black church. The Hampton Quartette, another all-black vocal group based out of the historically black Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, performed three times at the State Teacher’s College to great acclaim between 1928 and 1933. In October 1965, Madison hosted Little Royal and the Swingmasters along with the girl group The Shirelles, whose record “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1960 and was the first number one hit by an African American girl group in the US.

Harrisonburg’s black church. The Hampton Quartette, another all-black vocal group based out of the historically black Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, performed three times at the State Teacher’s College to great acclaim between 1928 and 1933. In October 1965, Madison hosted Little Royal and the Swingmasters along with the girl group The Shirelles, whose record “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1960 and was the first number one hit by an African American girl group in the US.

Dr. John W. Wayland’s book review

A letter dated 1911 from Julian Burruss, the first president of the State Normal School, to George Keezell, the President of Board of Trustees, and housed in the Burruss Records at Virginia Tech, notes that a four-room cottage had been built the previous year specifically for the African American employees in order to keep their working and living conditions satisfactory. Burruss, who took initiative to have the cottage built, reasoned that such an upgrade would be an incentive to keep those employees at the school and decrease the likelihood of them seeking work elsewhere. “The question of service is such a difficult one for us, and having secured some reliable and efficient help which we cannot afford to lose, I considered it very urgent that accommodations be provided for them on the school grounds, this being the only way in which we could keep them permanently in our employ,” Burruss writes. The cottage Burruss references would likely have been the “Cottage No. 2” labeled “Janitor’s Quarters” that appears on the Sanborn fire insurance map of Harrisonburg from 1930 (there is no listing for a “Cottage No. 1”). This building also appears in an aerial photo of the campus ca. 1930. The cottage itself stood just to the southeast of where the life-sized statue of James Madison is currently located in the quad area of campus. Available information on the school’s black employees during these early years is scant and awaits further research.

However, references to one Walker Lee, a janitor posted primarily at Science (now Maury) Hall, stand out. Dr. John Wayland mentions Lee in a typed account of a spelling bee that took place on the night of Friday, April 12, 1912 in Court House Hall in downtown Harrisonburg. The spelling bee was organized as a fundraiser for the new Methodist Church of Harrisonburg. Wayland notes that after the white men, women and children finished the spelling bee, “Some time later the colored people had a spelling bee, and Walker Lee, janitor of Maury Hall, then simply Science Hall, at the Normal, won out as champion.” The Student Welfare Committee meeting minutes dated October 25, 1911 also mention Lee: “A letter from the janitor, Walker Lee to Mr. Burruss requesting that if it is possible, a change of night for the meeting of the Literary societies from Saturday to Friday be made, was read. Regretting that we could not accommodate Walker for he has been very faithful, it was decided to be unwise to make the change.” Lee probably made the request because it would be more convenient for his janitorial duties. It is possible, given the early date of the letter and the comment that Lee was “very faithful,” that Lee was hired as part of the original staff when the school, then called The State Normal and Industrial School for Women, opened in 1909. Lee was employed at the school until sometime in the late 1920s when health issues no longer allowed him to work. His obituary in The Daily News Record dated May 21, 1929 reports on his funeral in Bridgewater. The article notes that “The funeral, held from the colored church here, was one attended by one of the largest crowds that have ever attended the funeral of a colored Bridgewater citizen. Many friends from the Teachers College in Harrisonburg attended. He had been employed at the college for many years. He leaves a widow and seven children.” Lee was buried in what was then the Ames Negro Methodist Church Cemetery, a plot of segregated burial land that separated it from Greenwood Cemetery. The fence separating the two cemeteries was removed sometime between 1983 and 1988. The May 22, 1929 issue of The Breeze also reports on Lee’s death, describing him as being “known by every student as a very familiar figure on the campus.” Despite faculty and students’ ostensible appreciation for the black employees, however, a derogatory caricature of African American housekeeping employees appears in the 1928 Schoolma’am.

Many friends from the Teachers College in Harrisonburg attended. He had been employed at the college for many years. He leaves a widow and seven children.” Lee was buried in what was then the Ames Negro Methodist Church Cemetery, a plot of segregated burial land that separated it from Greenwood Cemetery. The fence separating the two cemeteries was removed sometime between 1983 and 1988. The May 22, 1929 issue of The Breeze also reports on Lee’s death, describing him as being “known by every student as a very familiar figure on the campus.” Despite faculty and students’ ostensible appreciation for the black employees, however, a derogatory caricature of African American housekeeping employees appears in the 1928 Schoolma’am.

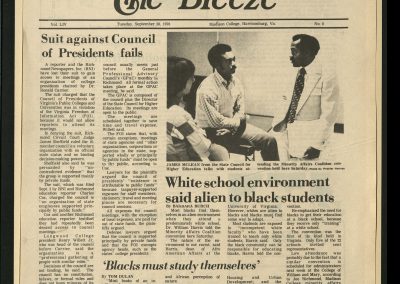

Students expressed mixed views regarding JMU’s implementation of Affirmative Action and recruitment efforts during the 1970s and 1980s. As various articles from The Breeze demonstrate, some students saw Affirmative Action as a tool for effective positive change, while others remained skeptical (see gallery below).