As Madison College the school expanded its educational scope to offer a greater variety of courses and become a multipurpose institution, though the primary focus of educating women to become teachers remained. Initially, the college held fast to its pointedly southern, conservative values while simultaneously expanding its size and enrollment. White supremacist culture still manifested through the performance of minstrel shows and blackface through the late 1960s. As the era of major Civil Rights sparked in 1954 and gained momentum throughout the 1960s, Madison seemed to register little impact. In 1964 a History of Africa course was offered for the first time, as well as a course on Race and Minority Relations. But it would not be until 1966, the year the college became both fully coeducational and officially integrated, that the college began to reflect the broader social and political changes shaping the national landscape.

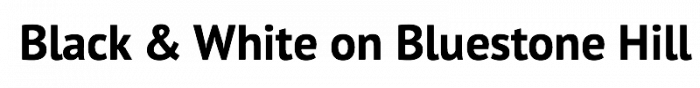

In the fall of 1966 Sheary Darcus Johnson enrolled at Madison College. Johnson became Madison’s first African American graduate, earning a B.A. in Library Science in 1970. She continued her education at Madison by completing her Master’s in 1974 before eventually earning a Ph.D. in education at the University of Virginia in 1988. The February 18, 2018 issue of The Breeze features an interview with Johnson, where she voices her respect for the school’s efforts to increase diversity. However, she also notes that another black female student who also enrolled in the fall of 1966, did not have a good experience. While Johnson attended as a day student, the other woman lived in a dorm where she experienced discrimination and harassment: “She had a much more difficult time by living in the dorm . . . The students were not nice to her. In dorm life, people can be more themselves perhaps than in the classroom and in larger areas of the campus.” Johnson goes on to mention that the student dropped out, leaving Johnson as the only African American student in her graduating class.

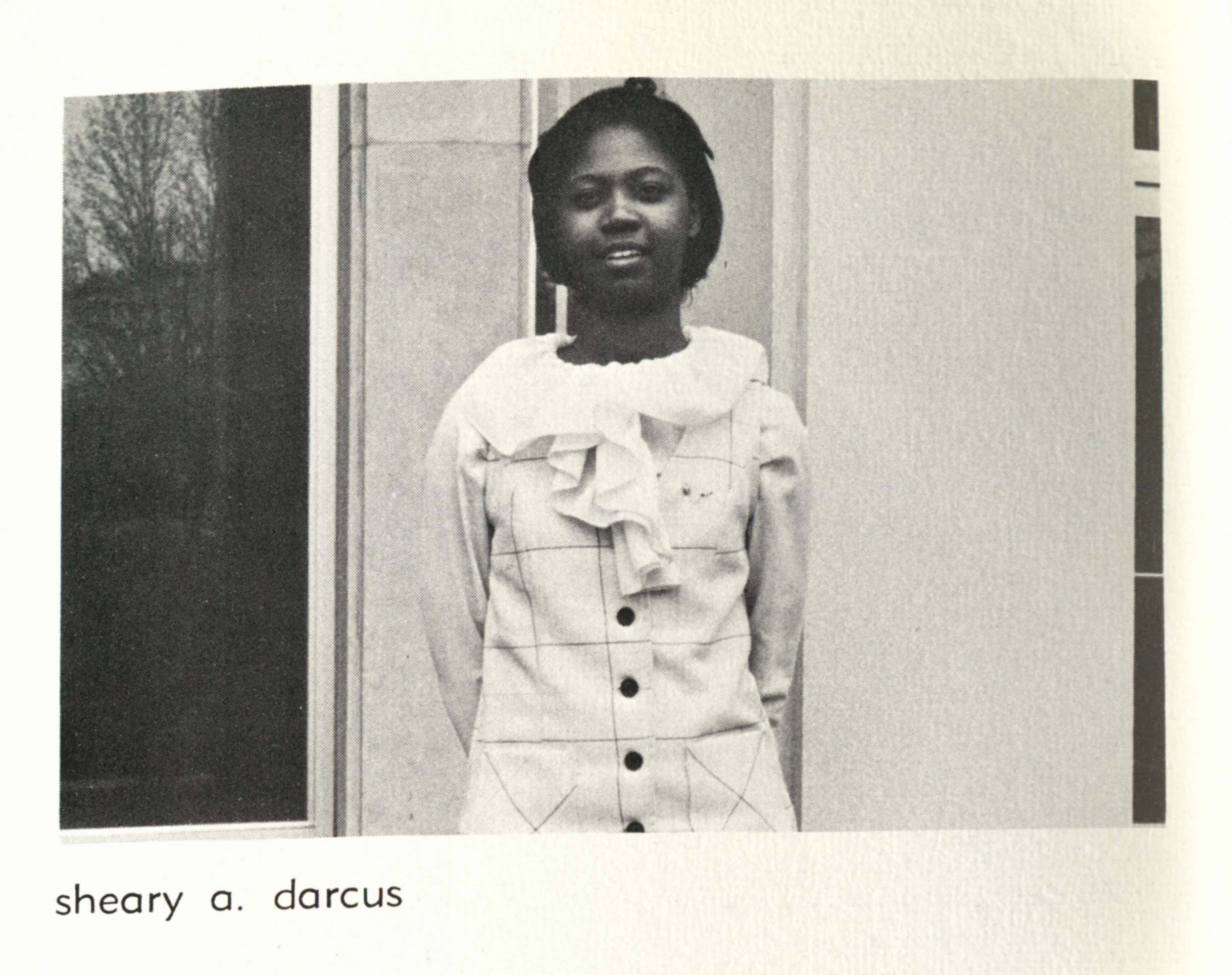

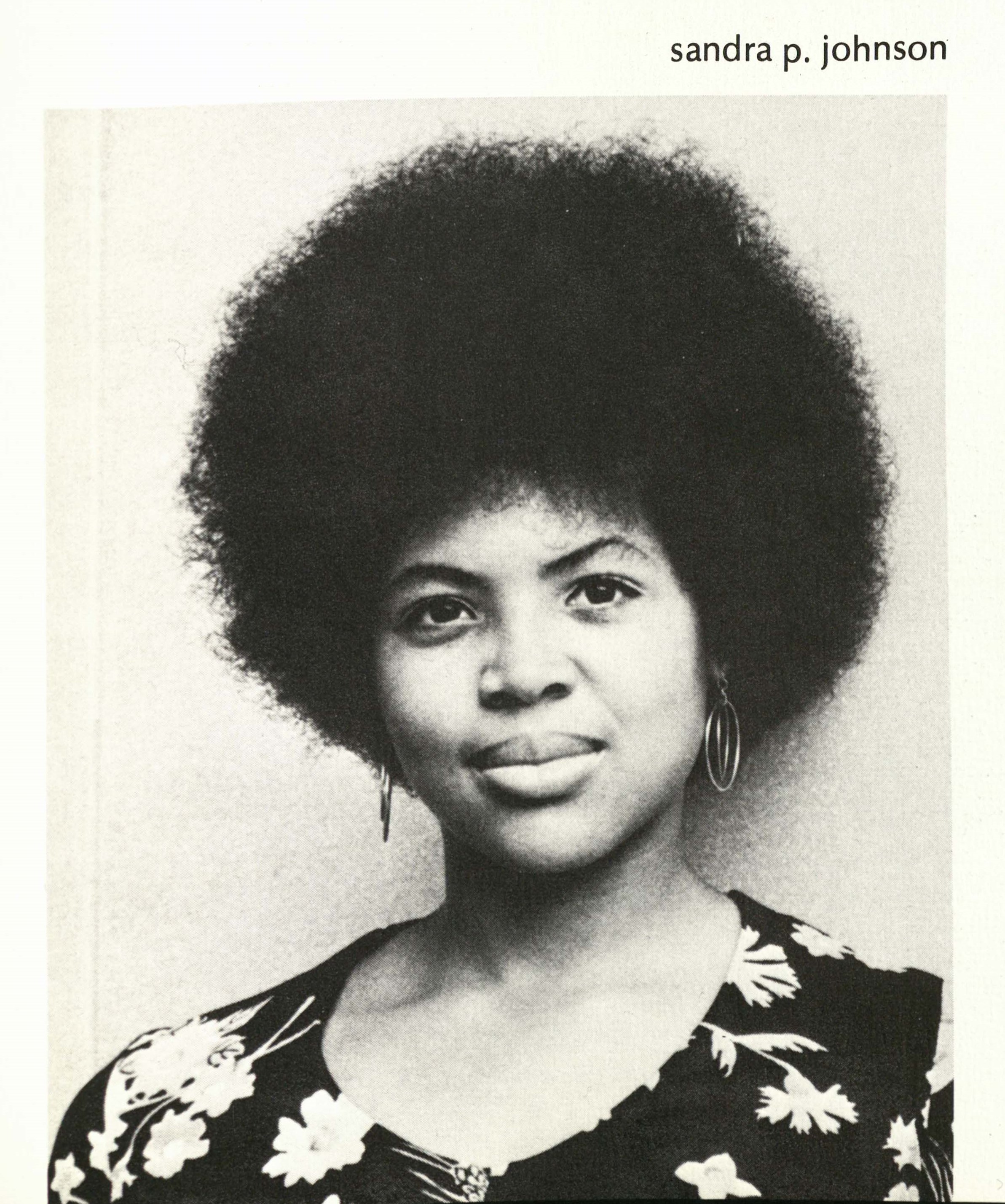

Following Johnson, the first male African American student, James Rankin, Jr., enrolled in the 1967. Rankin graduated in 1971 with a Bachelor’s of Science. In 1968, Sandra Johnson, Saranna Tucker, Janis Smith, and Purcell Conway enrolled and all graduated in 1972. Representation of Madison’s first African American students in the school yearbook Bluestone from this period is sparse. Only the aforementioned students have senior portraits.

Gallery: Early African American students at Madison

African American enrollment remained extremely low throughout the latter 1960s. This pattern, which the school would struggle with in subsequent decades, was rooted in various issues. Virginia senator Harry F. Byrd opposed the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas that ruled segregated schools to be unequal, and the additional ruling in 1955 that school desegregation must take place “with all deliberate speed.” Driven by Byrd’s policy of “massive resistance,” many schools in Virginia shut down in defiance of integration, sparking a number of law suits. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 technically prohibited discrimination in public places and provided for the integration of public schools, it did not guarantee any resolution of racial tension nor eliminate discrimination itself.

In the early 1970s Madison began implementing Affirmative Action programs by using “every good faith effort,” a rather dubious phrase. A 1973 Affirmative Action plan for faculty and staff set out goals to achieve “population parity,” or an equal proportion between the percentage of African Americans employed at the college and those employed in the Harrisonburg-Rockingham community, which at that time was 2.1 percent. In 1973, the percentage of black employees at the college was 1.4 percent.

By 1977 Virginia still was unable to meet desegregation guidelines congruent with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as a July 1977 letter from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to then governor Mills E. Godwin, Jr. reveals. The letter required Godwin to submit a revised desegregation plan within sixty days to the Office for Civil Rights. Godwin submitted a “Response to the Office for Civil Rights’ Comments on a Reformulation of the Plan for Equal Opportunity in Virginia’s Institutions of Higher Education: A Shared Responsibility.” In the document Godwin complains that numerical goals are unreasonable and that progress is surely being made. The Office for Civil Rights responded by expressing that Virginia’s revised plan was still too vague and inadequate. This sparked a letter from Godwin, which concluded:

“Such criteria do not become benign by being designated goals rather than quotas, nor do they become more palatable when accompanied by the threat of the loss of funds which would otherwise flow upon submission to them. Virginia’s hopes for higher education transcend racial quotas which are intrinsically at variance with Virginia’s commitment to equal educational opportunity and full academic freedom for all citizens of the Commonwealth” (letter from Godwin to David S. Tatel, Director of Office of Civil Rights, 12/15/1977).

The Office for Civil Rights responded again, this time stressing that numerical goals were not arbitrary quotas, but a reasonable expectation Virginia was supposed to exert “every good faith effort” to achieve (letter from David S. Tatel, Director of Office of Civil Rights to Godwin, 12/23/1977).

Black students at Madison finally gained a degree of representation during the early and mid-1970s. 1972 saw the establishment of Delta Sigma Theta, the first Black Greek service sorority, which worked with the greater black community. The Black Student Alliance was established in 1969 but began exerting greater influence over campus life in the early 1970s. As the 1970s progressed, the Black Student Alliance became a voice for the concerns of black students and was instrumental in making the campus more diverse. Additionally, it provided a welcoming space in the midst of what was (and still is at the time of this writing) a predominantly white college. The BSA also seems to have grown a bit exasperated with repeatedly having to tell white students that the organization was open to any students of the college—not just blacks—and that the whole point of the organization consisted of broadening minority awareness. In 1973 Madison established Black Emphasis Week, a series of events and performances that focused on African American history, culture, and art. At some point in the 1980s if not before, Black Emphasis Week became Black Emphasis Month for the entirety of February.