Policy and administrative efforts to make the campus a more inclusive learning and social environment for black students and faculty gained significant momentum in the late 1970s forward. This change was largely influenced by the Carter administration’s threat in 1978 to withhold $100 million in federal aid from Virginia’s public schools if the state continued to fall short of standards required by desegregation legislation. An article from the March 25, 1985 issue of The Breeze (“State to enforce reforms”) reveals that both JMU and Virginia’s public institutions of higher education more broadly continued to struggle with meeting standards set by Civil Rights reform during the 1950s and 1960s.

As part of 1978’s Affirmative Action plan, JMU’s numerical goal for new black enrollees by the fall of 1980 was 86; the actual number was 63. The total number of black students at JMU in 1980 came out at 268 out of a total student population of 8,817, or a little over three percent (Statistical Summary: December 1980. Office of Institutional Research, James Madison University)

From the Affirmative Action Student Plan, 1979-80 to 1982-83.

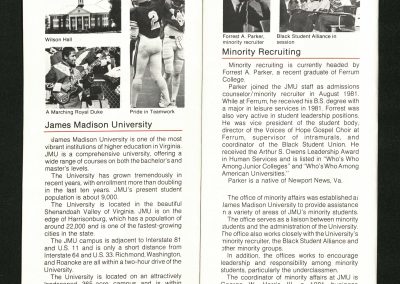

The 1980s were a period of vigorous activity for minority recruitment (“minority” almost always referred primarily to African Americans at JMU during the 1970s and 1980s, though there were a smaller number of other ethnic minorities enrolled, including Native American, Asiatic, and Hispanic). In 1980 the Affirmative Action Committee set forward a series of goals that included: greater representation of black students in campus publications; a plan for effectively publicizing black social events on campus; recruitment brochures; and an  official minority recruiter who would help develop a marketing plan for the recruitment of black students. Forrest Parker was hired as the first official minority recruiter in addition to serving as an admissions counselor in the following year. (“Summary.” February 6, 1980).

official minority recruiter who would help develop a marketing plan for the recruitment of black students. Forrest Parker was hired as the first official minority recruiter in addition to serving as an admissions counselor in the following year. (“Summary.” February 6, 1980).

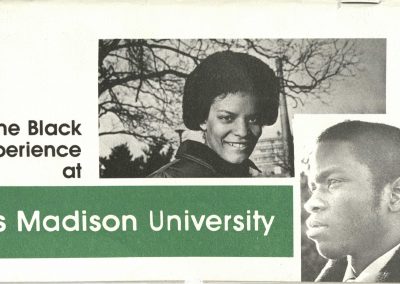

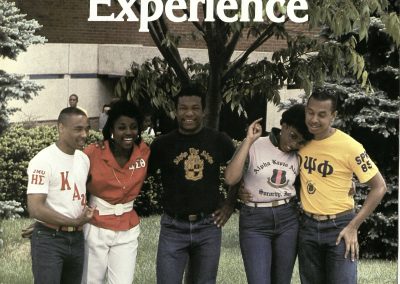

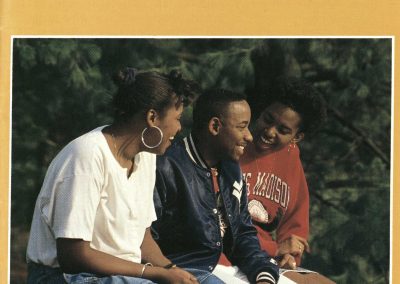

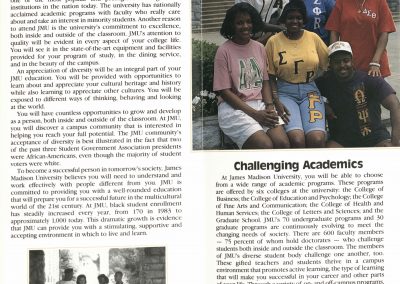

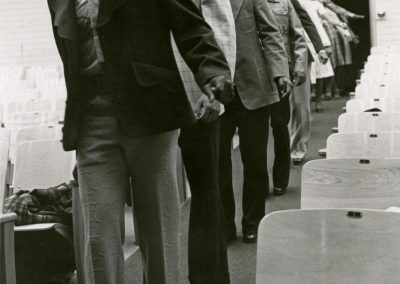

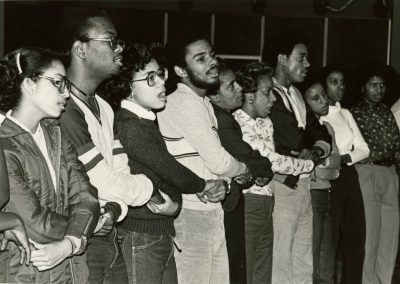

The Affirmative Action Committee began publishing “The Black Experience at JMU” in 1980, a recruitment brochure that aimed to depict JMU as an appealing and welcoming environment for prospective black students. The expansion of black Greek Life, Black Emphasis Week, the Contemporary Gospel Choir, the weekly radio program “Ebony in Perspective,” and the rising number of black students in general made up the centerpiece of these pamphlets, along with photographs of black students and faculty.

Gallery: The Black Experience at JMU recruitment brochures, 1980-1992

In response to student and faculty concerns with the small number of available courses on African and African American history and culture, the Interdisciplinary Afro-American Studies minor was introduced in the 1981 school year. This minor included a rich variety of courses in anthropology, history, music, literature, geography, and other disciplines. For reasons that are unclear, the minor disappeared in 1987. The Breeze took note of this absence and began interviewing faculty for an explanation. Comments were vague and generally evasive, but low enrollment was cited as a likely cause. In response to student demands, the minor was reintroduced in 1994, and in 2005 the name changed to its current title as the Africana Studies Minor.

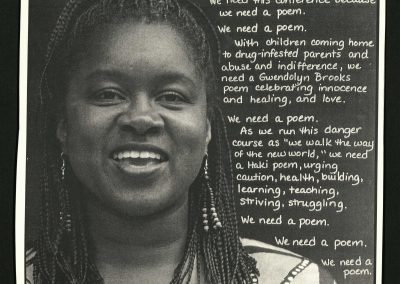

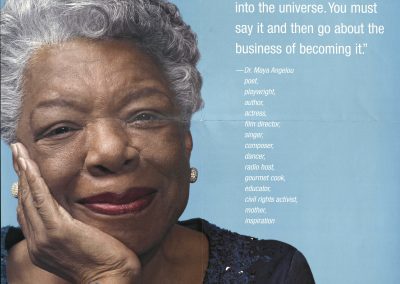

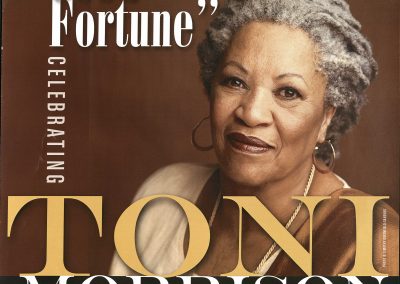

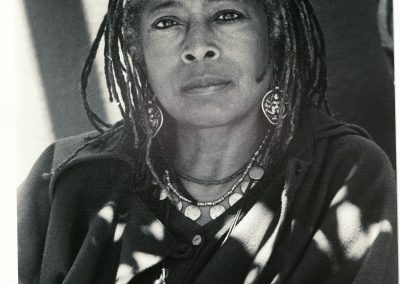

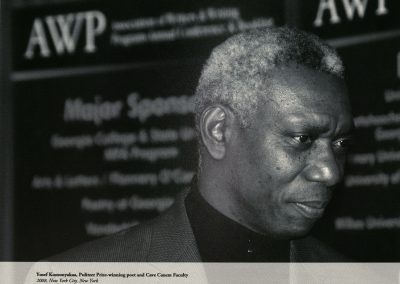

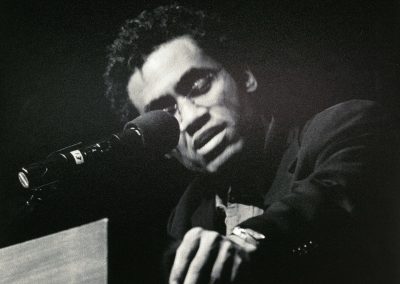

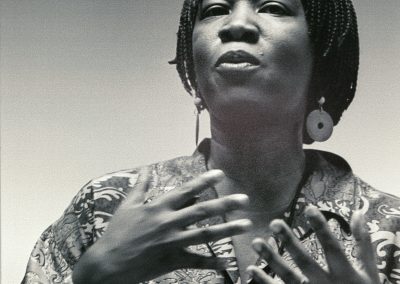

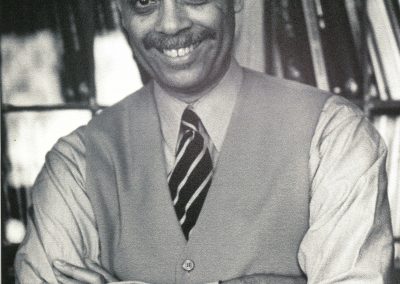

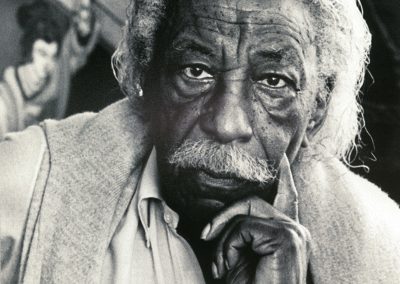

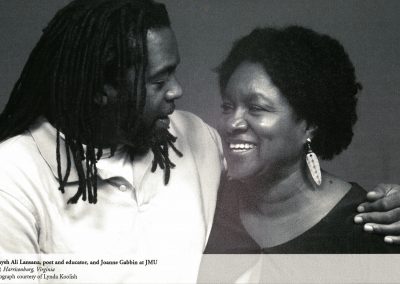

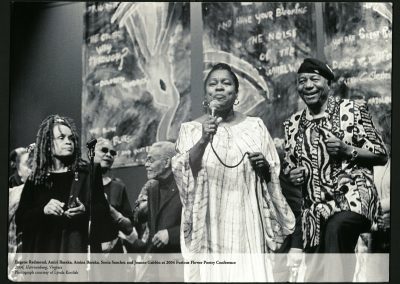

JMU made a giant leap forward in active diversity when Dr. Joanne Gabbin, distinguished scholar and professor of literature at JMU, established the Furious Flower Poetry Center, the nation’s first academic center devoted to Black poetry. Inspired by the poetic call to action in “The Second Sermon on the Warpland” by Pulitzer Prize winner and former U.S. Poet Laureate Gwendolyn Brooks, Gabbin organized the “Furious Flower: A Revolution in African American Poetry” conference in 1994. This event brought together numerous authors, scholars and enthusiasts of Black poetry on a scale unprecedented since the 1970s. It received national acclaim and led to a second conference in 2004, and Furious Flower was subsequently chartered as an academic center at JMU. The center’s variety of conferences, seminars, public readings, collegiate summits, and its children’s summer camp, testify to its importance not only for the university, but the larger Harrisonburg community as well.

In addition to the gallery below, see especially the interview with Dr. Gabbin on this site.