Pre-1985 JMU Special Collections

Post Author: Alexandra Kolleda

It is important to understand how significant a role Southern culture and history played on the campus of Madison College. Students took their history classes in Jackson Hall, named after the Confederate general “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson was one of the most accomplished generals in the Confederate army and fought against the emancipation of African Americans. Likewise, students lived in Ashby Hall, named after the Confederate cavalry commander, Turner Ashby, who was killed in the Shenandoah Valley, only miles from the Madison College campus. Did African American students find it difficult coping with the fact that they were living in an area rich with Confederate history and culture? Articles in The Breeze indicate that they did.

During Godwin’s first term as VA governor, he claimed integration would never occur

Pre-1985 JMU Special Collections

It is also telling that Madison College named Godwin Hall after the former Virginia Governor, Mills Godwin. As part of the powerful Byrd machine, Godwin agreed with former Virginia governor and Senator, Harry Byrd, that integration should be avoided at all costs (Smith, 24). Godwin’s wife graduated from Madison College; therefore, the naming of this building also reflects her role and continuity with the past.

Conversely, Governor Linwood Holton, who “personally escorted his thirteen-year old daughter Tayloe to predominately black John F. Kennedy High School” on the first day of mandated busing, does not have a building named after him. Holton’s act is especially meaningful, considering the Holton children were exempt from the busing plan, due to the governor’s mansion lying on state, not city, property (Pratt, 437). His courageous act in a hostile environment is definitely unrecognized on the Madison College campus.

Switching to the Republican party, Godwin ran for governor again and succeeded Holton. He performed an about-face on his anti-integration policy once back in office. Godwin accepted efforts to integrate Virginia colleges, including James Madison University’s 1978 Affirmative Action plan (Rosenthal, 258).

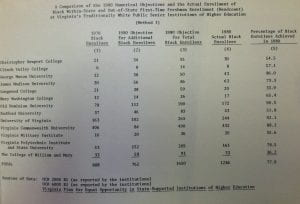

African-American Enrollment increased from 30 to 63 students between 1976 and 1980

Despite the celebration of southern heritage on Madison College’s campus, African American students were enrolling in increased numbers. “From 1969 to 1976, minority enrollment increased by 237 percent,” in Virginia institutions, illustrating the increased number of African-American students choosing to attend historically white Virginia colleges and universities (AA Plan 1978, 9). According to the chart displayed to the right, enrollment at Madison College alone increased by 110%, from 30 students in 1976 to 63 in 1980.

This increase in enrollment, despite the Confederate heritage present at Madison College, is most likely due to the active recruitment of African American students. What with President Carrier’s policies, minority students were not just allowed to come to Madison College, they were encouraged (Thomas, 2013). In the James Madison University Affirmative Action Plan in 1978, strategies were laid out for enrolling increased numbers of African-Americans. Black alumni were contacted in order for their assistance “in identifying prospective black students” (AA Plan 1978, 3). In addition, the Black Student Alliance was asked “to serve as tour guides or to speak to black students during their visits to the campus” (AA Plan 1978, 6-7).

Indeed, some of the first African American students to attend Madison College had positive experiences, because today, many of their children have chosen to attend James Madison University, following in their parents footsteps (Dean, 2013). The son of James and Saranna Tucker Rankin chose to attend the alma mater of his parents, both of whom graduated from Madison in the early 70s.

For more information about Madison’s southern culture see “Southernization” at http://sites.jmu.edu/mad70s/category/national-trends/southernization/

Continue to next post

Works Cited:

Dean, Arthur. Interview by author. Harrisonburg, VA. March 26, 2013.

James Madison University Affirmative Action Plan. James Madison University Special Collections. Harrisonburg, VA, 1978.

Pratt, Robert A. “A Promise Unfulfilled: Desegregation in Richmond, Virginia, 1956-1986.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 99, no. 4 (October 1991): 437.

Rosenthal, Steven J. “Symbolic Racism and Desegregation: Divergent Attitudes and Perceptions of Black and White University Students.” Phylon 41, no. 3 (1980): 257-266.

Smith, Douglas. “‘When Reason Collides with Prejudice:’ Armistead Lloyd Boothe and the Politics of Desegregation in Virginia, 1948-1963.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 102, no. 1 (January 1994): 5-46.

Thomas, Daphyne. Interview by author. Harrisonburg, VA. March 22, 2013.