This editorial shows town frustration over the radical university environment

Post by: Alexandra Kolleda

As mentioned in the introduction, town-gown relations between Madison College and the city of Harrisonburg were not very genial in the 1970s. In regards to the atmosphere of student protest that pervaded the entire nation, Harrisonburg citizens had a right to be nervous about the liberal student environment cultivated in their conservative city (Rainey, 1998). Madison College’s integration also threatened to overthrow the accepted social order in Harrisonburg.

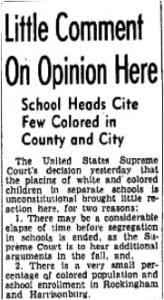

In 1954, African American students enrolled in Rockingham County and Harrisonburg schools only accounted for about 2% of the total student body (Daily News Record, 1954). When Brown v. Board declared integration imminent in 1954, the Harrisonburg Daily News Record declared that it was not concerned, because there were so few African-Americans in Harrisonburg (Daily News Record, 1954). The active recruitment of African-Americans to campus, however, threatened to increase the population. Nevertheless, it appears that integration in Harrisonburg was not met with defensive hostility. Instead, Harrisonburg residents adopted a sort of passive resistance. They were not necessarily in favor of integration, and they supported the local African Americans many white residents had grown up with; however, they were more hostile to those migrating into the community, including students enrolling at Madison College.

Daphyne Thomas describes her own experiences in Harrisonburg as slightly strained. A Black woman, she said that, while there was no outright hostility, whites in town were more wary about integration than Madison College faculty and administration were. She moved to Harrisonburg in order to work in admissions and faced discrimination when searching for a house to live in and a church to attend. She also noted the lingering impact of an urban renewal project in 1962, when Harrisonburg’s mostly white city council approved the purchase and demolition of its African American neighborhood over the objections of its residents. The historic African American Methodist Church was torn down in order to make a parking lot, and so were many homes and businesses. Kline’s Dairy Bar, a popular hang out for college students, is located on what used to be the black section in town (Thomas, 2013).

Steve Smith (’71), who was among the second class of white men admitted to Madison, remembered that African American students were not welcomed by town residents. In one instance, he and his African American roommate, Purcell Conway, went on a double date. They intentionally switched partners while walking downtown, making it appear as if they were two biracial couples. Smith remembers receiving a lot of shocking, racist comments from community members that night; when he discussed it with Conway later, he learned that such comments were often aimed at African American students who ventured off campus (Smith, 2013).

In a 1997 study, a white student named Todd Fisher interviewed two African-American residents of Harrisonburg about their experiences. The first interviewee, Elon Rhodes, had been a Harrisonburg resident his entire life, and claimed constantly throughout his interview that he experienced no sort of discrimination. He was elected to both the city school board and the city council where he served with white friends. Rhodes acknowledged that discrimination existed, however, he said he never experienced any of its negative side affects, except for his unequal educational opportunities. Rhodes’ children were moved from the all-black Lucy Simms School to Harrisonburg High School when Harrisonburg schools were integrated, and he says that he does not “recall hearing them complain about it” (Rhodes, 1997).

The second interviewee, Barbara Blakey, moved to Harrisonburg in 1955 at the age of 21 in order to teach at Lucy Simms School. A graduate of Virginia State University, she obtained a master’s degree from Madison College in 1971, and, like Rhodes, claimed that she “never had any problem, even going to James Madison.” After the integration of Harrisonburg city schools in 1964, Blakey became one of the first African American teachers at Harrisonburg High School. Her students were mainly white, however, she claims that she never saw racial differences and never experienced any problems with her peers or students. Blakey acknowledged that other African Americans experienced discrimination, but she felt that Harrisonburg did not follow the typical pattern of other Virginia localities (Blakey, 1997).

How to explain the differences between what Thomas and Smith shared about the 1970s and what Rhodes and Blakey recalled in the 1990s? It’s possible that Rhodes and Blakey, as members of an older generation, preferred not to share their actual views, especially with a white stranger. More research is needed to understand town-gown relations in this period. Although Harrisonburg’s white residents might have been less accepting of integration than Madison College faculty, it appears that the increased number of African Americans in Harrisonburg met with some resistance, but no outright protests or organized opposition. There was really not much Harrisonburg residents could do, and their acceptance of their own African American neighbors kept them grounded.

Continue to next post

Works Cited:

Blakey, Barbara. Interview by Todd Fisher. Harrisonburg, VA. April 2, 1997.

“Little Comment on Opinion Here.” Daily News Record 117, no. 9 (May 18, 1954): 1, 3.

Rainey, Jay. Interview by Jeremy Turner. Blacksburg, VA. January 30, 1998.

Rhodes, Elon. Interview by Todd Fisher. Harrisonburg, VA. March 18, 1997.

Smith, Steve. Interview by author. Harrisonburg, VA. April 2, 2013.

Thomas, Daphyne. Interview by author. Harrisonburg, VA. March 22, 2013.

Williamson, J.S. II. “Fashion Comes to Madison.” Daily News Record 73, no. 179 (April 29, 1970): 6.