Post Author: Mary Challman

As a former women’s college in the heart of Virginia, Madison College saw a great emphasis on being a “lady.” Womanhood was nothing short of celebrated; each year, a May queen was crowned (an honor that celebrated youth, beauty, and feminine purity), home economics was a wildly popular area of study up through the ’70s, and a statue of Joan of Arc was gifted to the college because she represented the ideal female – pure, religious, and obedient. Although this virginal ideal was obviously not upheld throughout the 1970s, a more regional ideal emerged within the women of Madison College that was maintained through the decade – the “New Southern Belle.” The development of the New Southern Belle coincided precisely with the development of the idea of Southernization throughout the United States, implying that these social developments were connected. John Lynxwiler and Michele Wilson typified the New Southern Belle (or NSB, for short) in their sociological study on the idealized woman in the contemporary South. In their article about the NSB, Lynxwiler and Wilson proposed a “code” to which the supporters of the NSB subscribed, and is applicable to women on the Madison College/JMU campus during the 1970s.

1. Status Consciousness – attention to status indicators such as material goods, knowledge of social rituals,and membership in organizations, sororities, and clubs. In the 1970s, Greek life exploded in popularity and sororities became an intrinsic aspect of the campus. In an article from The Breeze in October of 1970, a member of the Madison College Greek system described sororities and fraternities as a socially conscious organization that takes pride in how its member can function as a whole. However, sororities placed a heavy interest on how the organization presented itself visually, which denoted that some sort of status was associated with each particular organization. Members could distinguish themselves by wearing matching clothing and color-coordinating; in the same Breeze article, the author argued that by wearing the specific color of her sorority, a sorority member could “represent all the ideals and hopes of their [her] sorority” (The Breeze, 1970). The sorority girl pictured below demonstrates exactly this, not necessarily though color but through her Greek letter sweater. Wearing Greek letters in such a way to show that one was a member of a particular organization was wildly popular during the 1970s (as it is today). This overtly visual way of denoting which girl belonged to which sorority show the importance of sororities as status symbols on campus.

2. Honoring the “Natural” Distinctions Between the Sexes – Wilson and Lynxwiler say that “reliance on traditional sex roles is one of the was in which Southern women of most types differ from women of other parts of the country” (Southern Women, 117). Their acceptance and expectations to uphold these roles defines their roles as women. “Coquetry” was an important element of this role, and to succeed women were forced to hone this skill. Because the college had such a stratified difference between the number of men and women on campus, this skill became (and still is) prevalent among the women of the school; the lack of men forced women to excel in coquetry to be able to assume their role as a male dependent in an environment in which males were scarce. Additionally, women were encouraged to participate in traditional rituals of society, such as training to become a wife and mother. This concept was represented by one of the most popular clubs on campus, the Frances Sale Home Economics Club. The home economics program was designed to prepare young women to “serve from the home,” and as noted in the vast popularity of the Frances Sale Club, these women were more than happy to oblige. Pictured below, the Frances Sale Club was wildly popular and very active on campus throughout the 1970s, which reflects the popularity of the Home Economics program. As Madison College transformed into James Madison University in 1977, a Home Economics graduate program was even offered by the school. In the 1975-1977 graduate course catalog, three courses were offered under the Home Economics Program: HE (Home Economics) 501, Workshop in Home Economics, HE 540, Clothing Construction Techniques, and HE 680, Supervision of Student Teachers in Vocational Home Economics. Because both the undergraduate and graduate programs were so popular within the institution in the 1970s, it can be said that women greatly supported the notion of the “natural” differences between men and women, and were active in maintaining their traditional societal roles as women.

3. Remaining Loyal to the Southern Tradition – In their study, Lynxwiler and Wilson associate this aspect of the “code” with remembrances of the Civil War in the Deep South. Within the context of Madison College, the maintenance of the traditions that were held by the school since the early twentieth century shows that the students of Madison College did place an emphasis on “tradition,” a concept that is almost uniquely Southern (Southern Women, 118). One tradition in particular that was celebrated well into the mid-twentieth was the celebration of May Day. Traditionally, May Day celebrated feminine beauty and fertility; a May Queen was crowned to represent the women of campus and wore a white gown (representing innocence and purity) and presided over the celebrations. Because this tradition was celebrated for such a long period of time, the values that it reflected were clearly values that the people of the Madison College/JMU community supported. Pictured below, the similarities between the May Queen of 1913 and a May Queen in the late 1960s are striking. Both women wear white gowns and are covered in flowers; these similarities show the consistency of the values of this tradition. Although this tradition is not necessarily “Southern,” the importance of tradition to the Southern mindset is reflected in the maintenance of the May Day tradition on the Madison College campus.

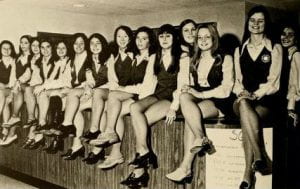

4. Obsession With Appearance – The NSB “craves confirmation of her appearance from others, especially males.” Although it is difficult to prove whether women on campus in the 1970s were dressing to impress the growing male population, the Madison Dollies, a club of young women who serve as the “hostesses of the campus,” show that there was a group of women who were fiercely conscious of appearance. To be in the Madison Dollies, a young woman must have “a 2.0 average, a pleasing personality, an attractive appearance, and a willingness to work with people” (Bluestone, 1972). The fact that there were more qualifications concerned with the overall attractiveness of the young woman than their wit or their intelligence shows that not only were the girls who participated in this organization focused on appearance but the administration was also more concerned with appearance. Seen in the below images, the uniforms that the Dollies were issued are evocative of the costume of a Rockette, that features a short skirt to highlight long, thin legs. This racy uniform that showed off a Dolly’s body insured that only beautiful, slender young women would be participating in this organization. Additionally, the gender inequality that was also unfortunately associated with the New Southern Belle is evidenced through this organization. By projecting that the women who participated in this club were only valued for their charm and good looks (as opposed to their intelligence, ideas, and opinions), those who supported this club and those who participated in this club were supporting the system in which it existed – a system that was distinguished by sexism. The idea of feminine subordination is even visible in the club’s organization; pictured in the image from the 1974 Bluestone, the faculty adviser was a male (Jim Logan). Because the organization placed a male as the leader of its ranks of scantily clad women, the organization was showing its support of the male-female gender disparity that existed within the 1970s.

The existence of the elements of the “code” of the New Southern Belle on the Madison College/JMU campus shows that the ideal of the Southern Belle was supported by many members of the institutional community. Because this idealization of Southern womanhood occurred on campus simultaneously with the Southernization of the country, it can be said that this support for the ideal of Southern womanhood that existed on campus in the 1970s was a result of the Southernization of America.

Works Cited

Control #Mayd302, JMU Historic Photos Online, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Va. http://www.lib.jmu.edu/special/jmuphotopages/mayd3.aspx

Control #Mayd310, JMU Historic Photos Online, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Va. http://www.lib.jmu.edu/special/jmuphotopages/mayd3.aspx

Graduate Catalogue: 1975-1977. Harrisonburg, VA: James Madison University, 1975.

James Madison University. The Bluestone. 1972. http://archive.org/details/bluestone197264jame

James Madison University. The Bluestone. 1973. http://archive.org/details/bluestone197365jame

James Madison University. The Bluestone. 1974. http://archive.org/details/bluestone197466jame

Lynxwiler, John, and Michele Wilson. “The Code of the New Southern Belle: Generating Typifications to Structure Social Interaction.” In Southern Women, edited by Caroline Matheny Dillman, 113-125. Philadelphia: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 1988.

“Member Explains ‘Greek’ System.” The Breeze. October 7, 1970.