Post Author: Alexandra Kolleda

By the late 1960s, integration was becoming a major federal initiative. President Johnson’s Executive Order of 1965, spelling out Affirmative Action, mandated that no institution could discriminate based on “race, color, religion, sex, and national origin, and [maintained] that affirmative action [guaranteed] all qualified applicants and employees the same equal employment opportunity” (Hasday, 111). Madison College’s integration, including their interpretation of Affirmative Action policies, differed from that of other institutions in the United States because of its particular circumstances. Not only was Madison a rural, southern campus, but it was also a public women’s college.

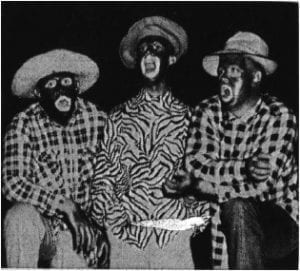

This article, written in the same year as Brown v. Board, shows how racism was represented in Southern culture and at Madison.

As a southern campus, the college was expected to uphold the socially and politically conservative values that promoted such practices as massive resistance to desegregation and white flight to new suburbs. It would be reasonable to assume that, like other southern institutions, Madison resisted integration. Indeed, Brown v. Board had ordered the integration of public schools with “all deliberate speed” in 1954, yet it was not until 1966 that Madison admitted its first African American students, two women. The delay illustrates the Miller administration’s initial compliance with Virginia’s efforts to avoid all measures of integration (Hall, 2009). Some members of the campus community were perhaps more willing to admit African American women than men. In A Red Record, Ida Wells Barnett noted the power of the unfounded fear that black men would assault white women (Wells-Barnett, 7). This fear likely affected how the desegregation of women’s higher education occurred. Madison College also became co-educational in 1966, and it ended up admitting many more white men than black men and women combined. In this way, white women were more protected.

Finally, strained town-gown relations in Harrisonburg affected desegregation efforts. Despite its small town location, Madison was caught up in the national student uprisings of the 1960s and 1970s. The April 1970 revolts, led by student activist Jay Rainey, strained relations even further as the conservative city leaders in Harrisonburg fought to control the more liberal students. In an oral interview, Rainey claimed that in addition to the April Revolts, some students also led a protest through town encouraging black civil rights, which exhibits the duality of the community (Rainey, 33).

Madison College provides an interesting study of integration in higher education because the campus was suspended between a conservative, southern culture and the more liberal, national student culture. This project will attempt to show how the two cultures collided in the College’s attempts to integrate.

Continue to next post

Works Cited:

Fosnight, Ann. “Senior ‘Plantation Party’ Offers Traditional Southern Hospitality.” The Breeze 33, no. 7 (November 1954): 1.

Hall, Kermit L. and James W. Ely, Eds. The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Hasday, Judy L. The Civil Rights Act of 1964: An End to Racial Segregation. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007.

Rainey, Jay. Interview by Jeremy Turner. Blacksburg, VA. January 30, 1998.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. A Red Record. London, The Echo Library, 2005.