Representation Under Different Electoral Systems: What does representation mean?

Billy McKeon, ’23 International Affairs Major with a concentration in Global Human Development, Madison Center Campus Vote Project Fellow

American democracy is founded on principles for providing fair and equal representation to all citizens, but how representative is it really? Are some democracies more representative than others? Professor Douglas J. Amy argues yes. In his book Real Choices / New Voices, Amy argues that democracies using proportional representation provide their citizens with a more representative form of government. Given the state of American politics, the arguments Amy presents are more relevant than ever. According to a study published by Pew Research Center, as of 2020 approximately 63% of Americans support replacing the Electoral College with a system prioritizing the popular vote. Another Pew study found American voter turnout lags behind that of many other countries, even after the historic 62.8% of eligible voters turning out during the 2020 General Election. Americans are not only questioning our electoral system, but are less interested in elections than most other democracies. Amy, along with other research, attributes this to a lack of representation.

Many intersectional forces play into an individual’s decision to vote or sit out an election. For example, Flavia Roscini argues that the news media landscape discourages voters from participating in politics altogether. Other factors include barriers to voting (which vary state to state and can take many forms)such as the issues on the ballot, political socialization, and sociopolitical status – to name only a few. So how can the U.S. increase participation in its elections? Amy suggests that different electoral systems produce different forms of representation, some of which can expand representation in several different ways.

What Voting System Does America Use?

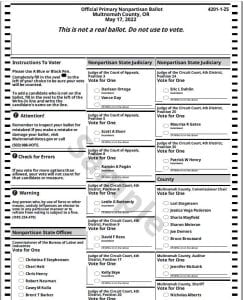

America uses single member plurality (SMP) voting in a majority of its elections. In this system candidates are selected one at a time in separate districts, and the candidate with the majority (or plurality) of votes wins. This system is used often at local, state, and federal elections. For example, Virginia’s governor Glenn Younking was elected by winning the plurality of the votes in Virginia. In gubernatorial elections, Virginia is considered one large winner-take-all district, and the candidate with the plurality (or highest percentage) of votes wins.

Representation is the process of an elected official bringing the needs of their constituents to the legislature they are a part of and presenting them to their colleagues. For example, Glenn Younkin signing and helping pass laws through the Virginia State Legislature is how he chooses to represent his constituency.

However, this is not the only form of voting in America. Over 100 cities use alternatives to single member plurality voting, which is additionally true for most other democracies. These cities opted instead for a form of proportional representation (PR). Proportional representation is a voting system that aims to allocate seats in proportion to the number of votes each political party or candidate receives. In other words, a party doesn’t have to win a majority or plurality (or the highest proportion of votes cast) of votes in order to be elected to office.

However, this is not the only form of voting in America. Over 100 cities use alternatives to single member plurality voting, which is additionally true for most other democracies. These cities opted instead for a form of proportional representation (PR). Proportional representation is a voting system that aims to allocate seats in proportion to the number of votes each political party or candidate receives. In other words, a party doesn’t have to win a majority or plurality (or the highest proportion of votes cast) of votes in order to be elected to office.

What Does Proportional Representation Look Like?

One form of proportional representation is the party-list system. In this, voters cast a vote for a political party rather than an individual candidate. Seats are then allocated to parties in proportion to the number of votes they receive. There are two forms: closed-list and open-list party systems In a closed-list, parties create lists of candidates, and the order of the list determines who will take the seats if the party wins. In an open-list, voters can pick which candidate they vote for an individual candidate from a list offered by political parties. This system allows third-parties to compete with Democratic and Republican candidates. For example, if one district is electing five representatives and there are five parties, then a candidate only needs 20% of the vote to win. This is a much smaller hurdle to overcome.

Another form is the mixed-member proportional representation system. This system combines elements of both single-member districts and proportional representation. Voters cast two ballots – one for a local representative and another for a political party. The local representatives are elected through a single member plurality system, while the number of seats allocated to each party at the state and federal level are adjusted to ensure that the overall outcome is proportional. States in this system would be composed of large, multi-member districts and voters would have many options to choose from. Advocates of proportional representation like Amy suggest that this would be a good system to help in the process of transitioning from single member plurality to proportional representation, since it incorporates elements of our current electoral system.

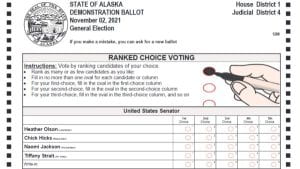

The last form is Single Transferable Vote (STV) system. This system allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. If a candidate does not receive enough first-preference votes to win a seat, their votes are transferred to their voters’ second-preference choices. This process continues until all the seats are filled. All of these forms allow the presence of third-parties by eliminating the threshold of gaining a plurality of votes in order to gain representation. In other words, all of these systems would expand representation in America as we know it today.

Benefits of Proportional Representation

One of the most direct benefits of proportional representation is the elimination of manufactured majorities. This refers to when a political party wins only a plurality of the votes (less than half), but gains a majority (more than half) of the seats and effectively lawmaking power. This has not only happened to the U.S. multiple times, but it’s also occurred for consecutive elections. For example, in both 1996 and 1998, Republicans won 48.9% of the total votes in the U.S. house elections, and 47.9% in 2000. Yet in each of these years Republicans won a majority of the seats (52.2%, 51.3%, and 50.8% respectively), granting them legislative power.

Proportional representation also drastically decreases the amount of “wasted” votes in a democracy. “Wasted” votes refer to ballots cast that do not result in any representation in government and vote for the losing candidate, for example, with third party candidates. With Democrats and Republicans always consuming such a large majority of the vote, it’s nearly impossible for a third party to be competitive in these elections. In proportional representation however, parties can gain representation with smaller vote percentages. This can allow marginalized communities who feel excluded from the two major parties to gain representation by casting only (typically) 10-20% of the total vote.

Voters who cast votes for third party candidates in consecutive elections are less likely to vote in future elections, assuming their candidate will lose. For example, a voter in Nancy Pelosi’s district explained, “Vote? Why Vote? I know who’s going to win” (Amy, p. 62). Some districts can become so one-sided that the opposing major-party stops running candidates altogether and surrenders the seat – leaving the voters with literally no choice. For example, either Democrats or Republicans refused to nominate a candidate in over 40% of contests for state legislature, which was lower than that of the 1998 state elections – 41.1%.

Voting habits also significantly increased as a result of proportional representation. For example, an analysis found that Cambridge Massachusetts held elections where over 95% of the electorate’s votes went towards the election of a candidate. Cambridge uses a single transferable vote election system.

Proportional representation additionally helps voters avoid what Amy calls the lesser of two evils ideology. This thinking describes voters who choose to vote for a candidate they don’t align with, but they do so to avoid the election of the alternative major-party candidate. For example, a poll found that over half of the voters who supported Biden in the 2020 Presidential Election, only did so because he “wasn’t Trump.” Pew Research found that nearly two in every five Americans express a desire for additional parties due to lack of affiliation with the two major parties, and the percentage of independents to be on the rise as well. Americans shouldn’t be forced to settle for candidates they elect.

Gerrymandering has been a long standing bruise on American democracy, with more Americans disapproving than approving our redistricting system. Gerrymandering involves incumbents purposely redrawing district lines to ensure their political survival. Sometimes we even see a sweetheart gerrymander, where parties agree to allow each other an equal number of “safe seats” through the redistricting process. However, proportional representation can help quell these competition-destroying “safe seats” because if more of one party is packed tightly into a district – they will simply win a higher percentage of the seats in that district. For example, in two 5-seat districts, a party could win 20% of the vote in one district, 80% in the other and gain 5 seats. They can also achieve this same outcome by winning 50% of the vote in each district. Additionally, larger districts would be allotted more seats in this system.

Lastly, campaigns in proportional representation systems are more issue-focused. When elections are between two candidates, we often see more mud-slinging, personal attacks, and conversations unrelated to socio-political topics on the ballot. In the first Presidential Debate of 2020, for example, was highlighted by Biden telling his opponent to “shut up,” and Donald Trump attacking his son in front of the nation. Amy describes that, “a multiparty legislature would encourage a truly pluralistic debate” and give voters more choices (104).

Conclusion

America can improve its system of democracy and expand representation through the adoption of proportional representation election systems. As Amy proves, replacing our single member party system with a mixed-member, single transferable vote, or party-list proportional representation system will give Americans a wider variety of political parties to choose from, encourage issue-focused campaigning, raise voter turnout, and practically eliminate gerrymandering.

But what does electoral reform look like in the U.S.? Amending our system of federal elections would require a constitutional amendment – a lengthy and difficult process. However, states and local towns have much fewer obstacles to overcome when amending their constitutions. In fact, dozens of states have reformed their constitution since 1970. Proportional representation will be implemented most easily at this level. We also must remember that there are powerful people and groups who benefit from plurality voting, and will fight hard to keep it in place. Amy suggests that individuals who are on the fence about proportional representation voting can look at its track record, saying “ Proportional representation has worked where it has been used” (172).

Recent Comments