By Dolores Flamiano

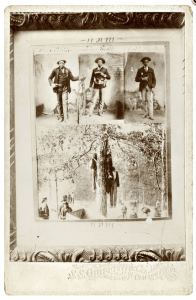

On Saturday, October 17, 1891, a group of young black miners traveled by train to Clifton Forge, a booming railroad town in western Virginia. Three of the men (Charles Miller, John Scott, and Robert Burton) visited S.S. Griffith photography studio and posed for Wild West-style portraits, displaying pistols and tough-guy stances. In high spirits and looking for a good time, they soon attracted the attention of a white man who tried to arrest them. (Newspaper accounts were vague about their alleged crime.) The miners resisted arrest and quickly left town, but a group of white men formed a posse and pursued them. The groups met in a firefight that killed two men (one white and one black) and injured two others. Four black men were taken to jail, but some white men (now an excited mob) kidnapped them. The mob decided to release a teenage boy, but proceeded to hang Miller, Scott, and Burton in a tree and shoot their bodies full of bullets.

S.S. Griffith apparently saw the Clifton Forge lynching as an opportunity to promote his photography business. He took the portraits of the three lynched men, combined them with a post-lynching photograph and attached the four images to heavy card stock to make a picture card, also known as a cabinet card. This was a popular format for portraits in the late 1800s that people would share with family and friends. This card told a simple “before-and-after” story of crime and punishment and a close look reveals “11 a.m.” above the portraits and “11 p.m.” below the lynching scene. The card was probably sold to people who wanted a souvenir of the lynching and as we will see, one of the images became part of the anti-lynching narrative. With “S.S. Griffith & Co.” in flowing script below an ornate border, the card also served as an advertisement for the business.

The 1890s was the country’s worst decade for lynching, when it claimed an average of 139 lives a year. Virginia, which took pride in having fewer lynching deaths than other southern states, recorded 40 in the 1890s. Most of what we know about lynching comes from white newspapers, but these sources are problematic. They not only reported racial violence, they also helped create it, especially with the rise of spectacle lynching in the 1890s. These public events drew hundreds of spectators (sometimes more) and were reported in news stories that usually framed lynching as a righteous act of vigilante justice.

This essay examines narratives of the Clifton Forge lynching in white newspapers, as well as counter narratives in a black newspaper, which included illustrations based on S.S. Griffith’s photographs of the lynching victims. In general, white lynching narratives have created and perpetuated harmful racial stereotypes and over time they have obscured some of the realities of lynching. An analysis of competing narratives about one specific lynching (Clifton Forge) illuminates what has been misrepresented and hidden, giving us a deeper understanding of a painful but important chapter in Virginia’s history.

Headlines: Vengeance or Murder

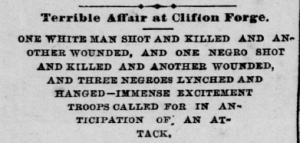

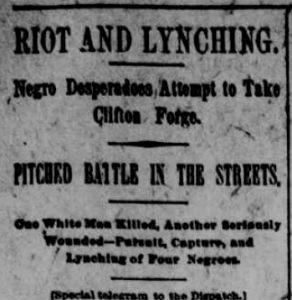

The lynching of Miller, Scott, and Burton was front-page news in Clifton Forge, Staunton, Roanoke and Richmond. The details varied from one newspaper to another but the overall narrative was remarkably consistent. Headlines assumed that white lives had more value than black lives. This can be seen in the precedence given to white killings in the Staunton and Richmond newspapers. Another theme is embedded in a Richmond Dispatch headline: “Riot and Lynching: Negro Desperadoes Attempt to Take Clifton Forge.” The desperado label cast the miners as outlaws without providing any evidence of their alleged crimes. The term also implied they did not deserve the same legal protections as law-abiding (white) citizens.

Against this backdrop, it comes as no surprise that the Clifton Forge newspaper justified the lynching with a two-word headline: “Swift Vengeance” and the Roanoke newspaper called the killings “executions” by “Judge Lynch”.

Incidentally, it was not unusual for lynch mobs to misappropriate the term desperado. In 1892, white newspapers used the term to justify the lynching of Thomas Moss and two other black grocery store owners in Memphis, Tennessee. Moss’ friend and the godmother of his child (Ida B. Wells-Barnett) knew he was no desperado. In fact, it was this lynching that inspired her to launch the anti-lynching crusade that became her life’s work. The Moss lynching revealed another ugly truth: lynching was sometimes a response to black men who were deemed too prosperous by their white rivals.

In Clifton Forge, white newspapers identified the miners as desperadoes to show that their killing was warranted and even necessary. This confirmed Fitzhugh Brundage’s observation that white news stories “warped the life histories of mob victims to fit the conventional portraits of black criminals.” Moreover, black men with nomadic jobs (like railroad workers or miners) “kindled hostility even without committing a crime.” The region’s growth also fueled racial tension. Between 1880 and 1890 the black population in Alleghany County (where Clifton Forge is located) grew from 1,132 to 4,013. In short, lynching became “a tool to define boundaries in a region where traditional racial lines were either vague or nonexistent.”

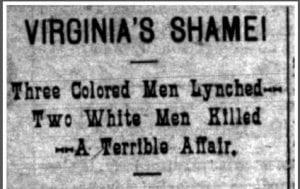

In response to the warped stories about black people in white newspapers, The Richmond Planet, Virginia’s leading black newspaper, told a very different story. “Virginia’s Shame!” challenged white newspapers’ disregard for black lives by listing black victims first: “Three Colored Men Lynched, Two White Men Killed” and a follow-up report promised the “true facts” behind the “murders”. It’s worth noting that none of the white papers called the lynching murder.

According to Susan Jean, opponents of lynching (like The Richmond Planet) confronted an enormous challenge in trying to strip white lynching narratives of their power. Newspaper headlines are revealing, but they are only the beginning of the story. To gain a deeper understanding of the Clifton Forge lynching narratives, it is necessary to take a closer look at the articles themselves. An analysis of their four-part structure (crime, pursuit, lynching, and aftermath) reveals the power of white lynching narratives. Equally important, it shows the difficulties The Richmond Planet faced in challenging racially charged rhetoric, correcting errors and inconsistencies, and giving voice to people in the black community whose words were omitted from the official lynching narratives.

The Alleged Crime

When they were lynched on the evening of October 17, 1891, Miller, Scott, and Burton stood accused of murdering one white man and wounding another. However, the Clifton Forge citizens who killed the three men saw them as outlaws before a single shot was fired—indeed, soon after they entered the town. What was their crime? The Staunton Spectator described the men as armed and dangerous outsiders (from Low Moor, a predominantly black mining town) who entered town “avowing it was their purpose to take the place.” It called them “boisterous in their boastings and misbehaving generally.” In other words, the men talked big and showed off. These activities were not crimes (at least not for white men), but they violated the norms of acceptable behavior for black men.

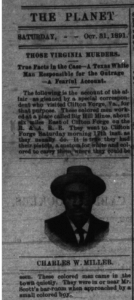

The Roanoke Times told the same story but used more sensational terms: the black miners reportedly told friends they were going to Clifton Forge for blood, for a fight, and to paint the town red, and then they “filled up on mean whiskey.” This article mentioned the photography gallery where Miller reportedly had his picture taken “with a revolver in each hand.” (the image shows one of Miller’s hands, but not both. Scott and Burton were also holding guns, but they were not mentioned here.) This raises questions about the picture card. For example, when was it sold and to what extent did it inform newspaper reports? If reporters saw the portraits of defiant black men posing with guns, what would they make of them? These images would have aligned with prevailing fears of dangerous black men and were consistent with the “desperado” narrative.

The Richmond Dispatch told a similar story but with even more salacious and exaggerated language, reporting that eight black men came to Clifton Forge from Big Island (another nearby mining town) vowing to take the town. They got drunk, armed themselves “with a brace of pistols” and “paraded the streets in regular western desperado style, flourishing their weapons and cursing and threatening all who approached them.”

In short, white newspapers told alarming stories about armed and hostile outsiders coming to Clifton Forge to “take the town,” a vague threat open to interpretation. At best, it could mean drinking and carousing; at worst, it could mean looting, rape, and even murder. The Richmond Dispatch’s description of black men “parading the streets” reminds us that public spaces were contested terrain in the 1890s. As noted, during the previous decade the area’s black population increased fourfold and so whites had more frequent contact with African American strangers. As Rand Dotson noted, some black men “refused to conform to contemporary white notions of appropriate black subservience.” Sidewalk confrontations in which white people perceived black men as disorderly or out of bounds sometimes led to lynching, and the presence of firearms surely made a tense situation worse.

The Richmond Planet reported some of the same facts as the white press. For example, it acknowledged that the miners went to Clifton Forge for a good time and “drank liquor freely.” But it eschewed labels like “desperadoes” and provided a different perspective on encounters with white townspeople: “several white men interfered with the miners” and launched a surprise attack on them after they left town to avoid trouble. When Miller shot and killed a man, he did so in self-defense. The Richmond Planet also provided context for the guns: “it is true they carried pistols, a custom for white and colored to carry them where they could be seen.”

The black newspaper covered the Clifton Forge lynching differently from the white press in another important way. It published illustrations of Miller, Scott, and Burton based on the portraits on the picture card. The Planet’s use of head-shots was consistent with its efforts to tell the life stories of lynching victims and to show them as flesh-and-blood individuals, not the stereotyped brutes and outlaws portrayed in white press accounts.

The Pursuit

After the miners left town, white men formed a posse and pursued them. This takes us to the next stage in the story, which includes the shootout, the killing of two people, the wounding of two others, and the jailing of the black men.

The Staunton Spectator reported that the posse commanded the black men to halt and both parties fired. Philip Bowling, a white brakeman was shot and instantly killed. Frederick Wilkinson, a white railroad employee was shot and wounded. The black victims, however, remained nameless and we learned nothing about their backgrounds: “One of the negroes was shot and killed and another wounded.” Four of the black men were captured, handcuffed, taken to town and put in the jail. “ According to the article, “great indignation and intense excitement prevailed.”

The Richmond Dispatch promised readers that the Clifton Forge report was by “Special telegram,” a claim supported by the article’s spare, “on the ground” style that mixed present and past tense and appeared to have been written on the fly. “The citizens formed a posse and attempted to disarm them. They resisted and a regular pitched battle occurred…. The battle became desperate, resulting in the mortal wounding of Fred Wilkinson and the instant killing of Philip Bowling, citizens of Clifton Forge… Among the rioters, Charles Miller, who killed Bowling, and Robert Burton, who wounded Wilkinson, are both wounded and captured. Robert Scott, another of the rioters, is captured.” The captured men were lodged in jail. “At 8:30 p.m. the city is full of excited people, many armed with Winchesters.”

The Roanoke Times gave a more detailed account of what happened to the black men after the shootout: Burton suffered a broken leg, Morton was wounded in the head, and Scott fled into the woods, “the blood streaming from his body.” Burton, Scott, Miller, and Morton were captured, carried to the city prison, and locked up.

The Richmond Planet provided a strikingly different account of events leading up to the shootout. Miller and his friends left town, saying they did not want to have any fuss. When they left, they did not know they were going to be followed. A white man asked the police to arrest “the boys” but was told there was no warrant for their arrest and so there was nothing he (the police) could do. This angered the man, who began “yelling like a mad-man, attracting many boys and men to join the chase.” The group approached Miller and his friends from the rear and fired upon them. Miller shot to defend himself and killed one of the white men. The black men were captured around 3 p.m. and lodged in jail.

The Lynching

According to The Staunton Spectator, at around 10:00 p.m., a large body of men (many masked) went to the prison, broke it open, took two of the black men, dragged them to Slaughter Hollow, hung them and riddled their bodies with bullets. They did the same to the wounded black man who was not at the jail. The Richmond Dispatch reported that a mob attacked the jail and overpowered the guard, took out four black “rioters and hung them to the railroad bridge” and riddled their bodies with bullets. (This was the only report that called the black men “rioters” and the only one that got the location wrong.) The Roanoke Times dramatized the story by reporting that the white mob “broke down the prison doors with two large sledgehammers” and blurred the line between news and opinion: “Nobody at Clifton Forge needed to be told that Judge Lynch would arraign the prisoners and execute them as soon as the mantle of darkness fell.” By invoking the name “Judge Lynch” the Times implied the outcome was inevitable and no one was responsible. The reporter took pains to portray the mob as orderly and quiet: “Some three hundred men gathered near city hall and in a respectable manner informed the mayor of their intention.” The mayor pleaded with them but seeing that it was futile, “asked the leader to go quietly about his work.” The black men were drawn up to the tree limbs with ropes and then “volley after volley was fired at the bodies… over forty finding lodgment in Miller’s.”

In comparison to the white newspapers, The Richmond Planet provided conflicting reports, as well as details apparently obtained from black townspeople. For example, it reported “the Mayor made no effort to prevent the lynching” and “the men did not break open the jail but the keys were furnished them.” The Planet also gave a chilling account of preparations for the lynching, which seemed very methodical. For example, stores were ordered not to sell weapons or ammunition to black men. Meanwhile, stores sold firearms to white men and gave them to “those who couldn’t buy them.” Bars and markets closed and “nearly every white citizen in town” (300-400 people) allegedly “joined the lynching party.”

The Planet noted the lynching took place at the [animal] slaughter pens near the city limits and that the men who did the lynching wore their usual clothing, with no disguises. This contradicted The Staunton Spectator’s report of masked men. The Planet also identified some of the people involved (by occupation, not name). For example, a butcher who mostly served the black community “took a leading part in tying the rope” and “a white doctor took part in the hanging by counting the time.”

Most notably, The Planet included information that confirmed the lynching was designed to terrorize the black community. The hanging tree was located within 50 yards of black people’s houses and when men in the mob fired pistols, they did so “in all directions and dared (people) to poke their heads out of doors.” Nonetheless, a black woman defiantly told the lynching party she “would die with the men and stood right by the tree during the awful murder.”

The Aftermath

Two themes dominated the post-lynching story in the white press: the restoration of peace in the town and rumors of an attack by black residents of nearby mining towns who wanted revenge for the lynching.

Some reports claimed that in the aftermath of lynching the community experienced a kind of redemption. The notion seems bizarre on its face, but it was presented with solemnity in some newspaper accounts, with reporters waxing poetic on the subject. The most dramatic description of the immediate aftermath of lynching appeared in the Clifton Forge and Iron-Gate Review: “In less than an hour the streets of Clifton Forge were as quiet as a churchyard. The moon was shining almost as bright as day. It bathed in a silvery light the ghastly faces of the three misguided men who were left hanging on the tree.” Similarly, if less poetically, The Staunton Spectator reported that after the lynching the town became quiet and not a black man was to be seen. It also reported rumors of a possible attack on the town in retaliation for the lynching, which led the town to ask Gov. McKinley for troops. The paper also reported an inquest that returned the following verdict: “the men were hanged by parties unknown to the jury,” a standard component of the white lynching narrative overall. The Roanoke Times also reported rumors of a counter-attack in revenge for the “lynching of the desperadoes.” The end of the article (seemingly an afterthought) listed alleged offenses by Miller the previous year, including firing shots on a citizen of Buchanan who attempted to arrest him and attempted murder of a railroad conductor.

The Richmond Planet reported the rumors of black people planning to avenge the lynching, but did not give the reports much credence. It also provided background information about the black victims, notably John Scott of Irwin, Virginia, described as a quiet, law-abiding citizen. It did not have much to say about Miller, except to identify his home as Big Island. John Mitchell Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet, noted in the article that he telegraphed to Clifton Forge and received the photographs from which the illustrations [head shots of the victims] were made. It appears that Mitchell received the picture card with the miners’ portraits and the lynching photograph. The Planet’s illustrations omitted the portion of the portraits with the pistols.

“You Shudder at the Picture”

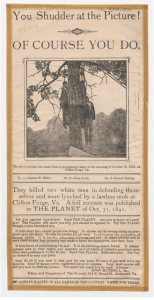

Broadside Advertisement (“You Shudder At The Picture, Of Course You Do.”) The Richmond Planet, Ca. 1891

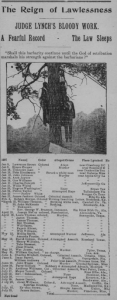

In the years after the Clifton Forge lynching, The Planet published illustrations based on the lynching photograph, pairing them with headlines of outrage that spoke directly to a black audience: “You Shudder at the Picture” and “The Reign of Lawlessness”. White newspapers presented the lynching as a warranted instance of vigilante justice. In the black newspaper’s counter narrative, however, the Clifton Forge lynching was nothing more than the murder of black men acting in self-defense.

The Richmond Planet’s broadside advertisement “You Shudder at the Picture” was designed to attract new subscribers and articulate the newspaper’s anti-lynching campaign. The focal point was an engraving based on the Clifton Forge lynching photograph. It’s important to note that the Planet took some liberties with the original photograph, creating a more minimalist visual by obscuring the white spectators and changing the background. This was probably an attempt to create an iconic symbol of lynching rather than a document of a specific incident.

The headline (“You Shudder at the Picture”) acknowledged the horrific nature of the image, especially for a black viewer who might reasonably think, “That could be me or my loved ones.” The next line (“Of course you do”) affirmed a connection with the reader and a shared humanity. The advertisement also identified the lynching victims and briefly explained the circumstances leading up to their murder. Yes, they killed two white men, but they did so in self-defense. The rest of the advertisement (about one-third of the space) declared the Planet’s commitment to justice, human rights, and maintaining the rule of law.

“The Reign of Lawlessness” was a two-column wide graphic updated weekly. These statistical tables documented the lives lost to lynching nationally every week for most of the paper’s forty-five year run. Equally important, as Jacqueline Goldsby pointed out, the feature documented the black community’s work to comfort and support the survivors of lynching: “efforts at restoration and repair were reported, describing the recovery of lynching victims’ bodies, the funeral and burial rituals, and the fundraising campaigns mounted to aid suffering families.”

“The Reign of Lawlessness” (like “You Shudder at the Picture”) was illustrated with an engraving based on a photograph of the Clifton Forge lynching. Beneath the main headline were three smaller ones: “Judge Lynch’s Bloody Work,” “A Fearful Record,” and “The Law Sleeps,” followed by a question: “Shall this barbarity continue until the God of retribution marshals his strength against the barbarians?” Finally, the graphic listed the people lynched that year to date. The information was presented in a table with five columns: year, name, color, alleged crime, place lynched, and number of people. Incidentally, the alleged crimes ran the gamut from “nothing” to “writing insulting letter” to “murder.” This graphic stood as a grim weekly reminder that lynching claimed the lives of black people every year, including some accused of no crime. As such, it paid tribute to the victims of mob violence and heaped shame on lawless places where lynching flourished because local authorities allowed the perpetrators to go free.

The Richmond Planet’s response to the Clifton Forge lynching would prove instrumental as a model for how the black press would counter white narratives of lethal mob violence. “The Reign of Lawlessness” was a precursor to similar features in Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s pamphlet A Red Record (1895) and the NAACP magazine The Crisis (notably 1912 and 1930), and the black newspaper The Chicago Defender (1930).

The fight against lynching was also a cultural contest about the meaning of lynching in the South and the nation, and the role of black press, activists and organizations like the NAACP to challenge the dominant white narratives. As we have seen, white newspapers condoned racial violence through headlines, editorial commentary, and narratives that presented lynch mobs as peacekeepers.

This essay is a small part of a larger effort to commemorate the lives destroyed by lynch mobs (over 4700 nationally) and to expose and challenge the myth that lynching amounted to (in a Clifton Forge headline) “swift vengeance.” Two notable recent initiatives are the website Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia, 1877-1927 and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Memorial) in Montgomery Alabama. The website and museum (and other efforts across the country) commemorate victims of lynching, acknowledge past acts of racial terrorism, and advocate for social justice.

Works Cited

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Dotson, Rand. “Race and Violence in Urbanizing Appalachia: The Roanoke Riot of 1893.” In Blood in the Hills: A History of Violence in Appalachia, edited by Stewart Bruce E., 237-71. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jcv2d.14.

Goldsby, Jacqueline. A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Jean, Susan. “‘Warranted’ Lynchings: Narratives of Mob Violence in White Southern Newspapers, 1880–1940.” American Nineteenth Century History 6, no. 3 (September 2005): 351–72. doi:10.1080/14664650500381058.

Wolfe, Brendan and Laura K. Baker. “Lynching in Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 7 Nov. 2016. Web. 17 Jul. 2019.

Dolores Flamiano is a professor in the School of Media Arts and Design at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, where she teaches media literacy and media criticism. Her research and writing focus on photography history and she is the author of Women, Workers, and Race in Life Magazine: Hansel Mieth’s Reform Photojournalism, 1934-1955 (Routledge, 2016).

Thank you very much for information. Do you have anything on Bristol, Va and Bristol, TN specifically?

The example of the Richmond Planet is a good model.

Adrienne, I do not have anything specific about Bristol VA/TN. However, the Black in Appalachia organization has produced a lot of information about the 1891 lynching of Robert Clark in Bristol TN; here you can find a short documentary about the lynching: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPFZ99Xg3II

I have a photo of the Griffith Studio taken in early 1900s (?) and another from another time (neither photo is dated unfortunately). It was located above the Murray & Foster Dry Goods store on Ridgeway Street.

There is a horse-drawn delivery buggy as well as an early automobile decked out in patriotic decor in the photo in which the name of the studio is clear.

Incidentally, the side of the same building has the carved names of the young couple whose elopement was foiled and they jumped into the river in 1907 (Mabel Pendleton and Charles Stuart Gay). Their photo is etched in color on their tombstone, still in excellent condition 117 years later.

Great information, descendents of the Young family , low Moor ,VA.

many of us have important ancestry to US history. further back into slavery ..Blacks with black & white ancestry..

America is home, and so much of this history is crucial history … but more so the children could unite & do better for the prosperity of future America. thank you for what you do