By Zoe Crihfield, Tom Costa, Dylan Mabe, Thomas Noble

On June 5, 1902, Wiley Guynn, a 28-year-old boarding house proprietor and miner, was arrested for assaulting the twelve-year-old daughter of Franklin Green, a white farmer living in the Tom’s Creek area, just outside Coeburn in Wise County, Virginia. Guynn allegedly grabbed the young girl who screamed, attracting a group of white men who apprehended Guynn. He was taken before a justice at Bondtown and given a hearing; as he was about to be jailed, a mob of close to five hundred men, including the girl’s father, descended on the jail demanding the prisoner. As they conveyed him away from the jail, he broke free and was shot to death trying to escape.

Guynn’s was the first recorded lynching of a black man in Wise County. The county had been relatively free from extreme forms of racial violence since the end of the Civil War, but Guynn’s death would be the first of three racial lynchings in Wise. After a lull that lasted through the end of WWI, a black man named David Hunt or Hurst was victimized in 1920, and then in 1927 came the lynching of Leonard Woods, which would prove to be the last recorded lynching in the state. Certainly, African-Americans were subject to extra-legal violence in Virginia after 1927, and while the NAACP continued to investigate violence against blacks as lynchings at least until 1937, Virginia officials explained such incidents as suicides or accidents (see especially the 1936 case of William Wales, Gordonsville, in NAACP Administrative Files, Sub. File Lynching – Virginia, 1914-1937).

While the three Wise County incidents contained characteristics common to lynchings across the South, including accusations of black violence against whites, the gathering of a mob to exact extra-legal punishment, and with one crucial exception, the failure to prosecute the lynch mob’s members, each had aspects beyond the elements of racial terror which may help explain mob violence in Wise County. Wise County officials, for example, unlike many in other parts of the South, made great efforts to prevent lynchings and even prosecuted participants. Yet even when local officials prevented lynchings, African-Americans were forced to contend with heightened racial tension and the possibility of further violence from the white community.

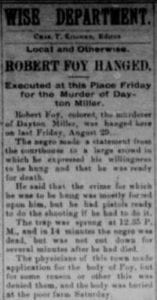

The 1902 killing of Wiley Guynn is a case in point. The previous December, a black man named Robert Foy shot and killed Dayton Miller, the Treasurer of the Crane’s Nest Coal and Coke Company, located at Tom’s Creek north of Coeburn near where Guynn operated a boarding house. An employee, Foy had rented a house from the company, but did not occupy it. When he learned that the rent had been deducted from his pay, Foy allegedly “became abusive,” shooting Miller and wounding another white man named Charles Williams. (Big Stone Gap Post, Dec. 26, 1901). One local paper expressed little doubt of what would become of Foy, predicting his lynching if a “determined mob appeared.” But Foy escaped the mob and remained in jail throughout most of 1902. An initial hasty verdict of guilty was thrown out; a subsequent trial resulted in another guilty verdict and he was sentenced to be hanged in March, but this verdict was appealed. After more delay, including a jail break, recapture, and an outbreak of smallpox among the prisoners, Foy finally met his end in a public hanging on August 29th, 1902 (See Big Stone Gap Post, September 4, 1902, for details of Foy’s execution). The seemingly long delay of justice, and the newspaper coverage of Foy’s case throughout that spring and summer more than likely heightened racial tensions, resulting in the quick execution of Wiley Guynn, who lived in the same area. According to newspaper accounts, soon after Guynn’s apprehension, he was housed in a local lock-up in Bondtown, the black section just north of Coeburn. Wise Commonwealth Attorney W.G.G. Dotson rushed to the scene and pleaded with the mob to allow justice to take its course. The mob, which undoubtedly included men who were familiar with Foy’s killing of Miller, as well as the father of the young girl Guynn allegedly assaulted, rejected the plea, took Guynn from custody and pointed him in the direction of a tree on which they intended to hang him. Guynn broke and ran then died in a hail of gunfire, described as “a volley of about twenty-five shots” (Richmond Dispatch, June 8, 1902, Roanoke Times, June 7, 1902).

There wouldn’t be another recorded lynching in Wise for eighteen years. But following the First World War, as emboldened black soldiers came home and rising tensions involving fears of Communism led to numerous racial incidents all over the United States, David Hunt (or Hurst) was lynched by a white mob after being accused of assaulting an elderly white woman. On a November evening in 1920, Hunt allegedly broke into a home in Cane Patch, near Appalachia, Virginia, attacking the woman inside. Soon captured, he was taken to the county jail in Wise. A mob quickly gathered, broke Hunt out of jail and took him to the neighborhood of the scene of the crime and hanged him, either from a railroad bridge, or a coal tipple.

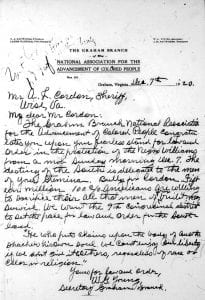

Wise County Sheriff A.P. Corder was unusual among southern lawmen in that he placed service to justice above racism. In the Hunt case, he arrested several members of the mob, and two were later convicted of inciting a riot and sentenced to a year in prison. Corder believed that had he received timely warning, he might have prevented Hunt’s lynching. Commonwealth’s Attorney C.R. McCorkle agreed, arguing that “Sheriff Corder’s expected sources of information failed him for some unknown reason.” Three weeks later, the Sheriff proved his point when he received notice of an attempt to lynch a black man named Sydney Williams, who had been jailed for assaulting a white storekeeper in Appalachia. Calling out extra deputies and arming them with a machine gun, Corder was able to repulse two separate attacks on the jail, killing two white men and wounding several others. Williams was safely conveyed to Roanoke by train (Roanoke Times, Dec. 7, 1920). Corder’s defense of Williams impressed even the NAACP, whose Graham (now Bluefield) chapter sent a letter commending him for his “fearless stand for law and order in the protection of Negro Williams.” The Wise County Sheriff’s actions were the exception to the actions of most southern lawmen, who either stood aside, or actively participated in lynchings.

It would be another seven years before the final recorded lynching in Wise County. The sensationalism and national attention that accompanied the lynching of Leonard Woods in 1927 at Pound Gap became the impetus for Governor Harry Byrd to push through the state’s first anti-lynching law. Following its passage in March 1928, there would be no more recorded lynchings in the state, although violence against blacks would continue as noted above.

On November 19, 1927, the people of Wise County, Virginia and Letcher County, Kentucky met at the states’ border near Pound Gap to witness Governor Byrd of Virginia and Governor Fields of Kentucky celebrate the opening of Highway 23. For the occasion, a platform was built on the side of the road from which the two governors spoke. In retrospect, the greater significance of the platform was not highway inauguration, but rather one more insidious. Just a week after the event, the platform became the site of the lynching of Leonard Woods for the alleged crime of murdering Herschel Deaton.

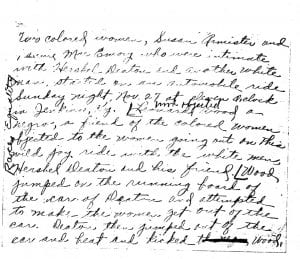

A little over a week after the grand celebration, Herschel Deaton along with two friends, Bill Townsend and Ernest Jordan, traveled from Coeburn across the mountain into Kentucky. As they approached Slick Rock, the black section just outside Jenkins, KY, they were met by Leonard Woods, a black miner, and two women, Susan Armister and Anna Mae Emery, and in an ensuing confrontation, Woods shot and killed him. The reason for the violence remains uncertain, but there were two primary narratives. The official version was that Woods and the two women demanded a ride and when Deaton refused, Woods shot him. The unofficial account is that Deaton and his friends came to Jenkins looking for the women, and Woods “objected to the women going out on this wild joy ride with the white men.” He and Deaton argued, may have fought, and Woods shot Deaton (Anonymous letter to Carl Murphy, editor of the Baltimore Afro-American, Dec. 17, 1927, in NAACP Administrative Files, Sub. File Lynching – Whitesburg, 1927-28). Whatever the real story, a black man killed a white man. Woods, Armister, and Emery were arrested the next day and held in a small jailhouse in Jenkins before being moved to Whitesburg, Kentucky for safer keeping. (See the Norton, Coalfield Progress, November 30, 1927 for the official account; Crawford’s Weekly, December 3, 1927 included doubts about the official version. See also Alexander S. Leidholdt, “’Never Thot This Could Happen in the South!’ The Anti-Lynching Advocacy of Appalachian Newspaper Editor Bruce Crawford,” Appalachian Journal Vol. 38, No. 2/3, Winter/Spring 2011, pp. 198-232.)

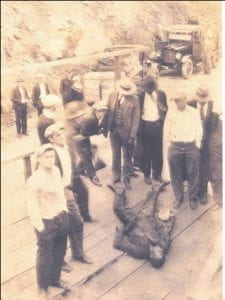

Two nights after Deaton’s death, following his well-attended funeral, a large number of people traveled through the Gap heading for Whitesburg. This mob, unmasked, broke Woods out of jail, sparing Armister and Emery, and headed for Jenkins. Forestalled from lynching Woods near the scene of the alleged crime, they took Woods to the top of Pound Gap and on the platform where the two governors had celebrated a week or so earlier, they hanged Woods, shot him, and burned his lifeless corpse. Woods’ lynching garnered particular attention owing to the fact that it took place on a state line, creating a jurisdictional dispute in which the governors of Virginia and Kentucky each claimed that it occurred in the other’s state. Furthermore, no member of the mob, several of whom were known, was prosecuted. Curious locals, including school children, visited the site of Woods’ death for some time after, in such numbers that two weeks later, the wooden platform collapsed (D.B. Hollyfield, “Stories True and Real in the Life of D.B. Hollyfield,” oral account, recorded July 6, audio CD issued 2005).

The sensation that Woods’ lynching created was one that Virginia Governor Byrd could not ignore. In March 1928, he convened a meeting of concerned officials, including local Norton, Virginia, newspaper editor Bruce Crawford (who had published accounts that cast doubt on the “official” version of Deaton’s killing). At Byrd’s urging, the Virginia legislature passed the state’s first anti-lynching legislation, empowering state officials to investigate and prosecute lynchings. Subsequent instances of violence directed against African-Americans were less public, fewer whites took part, and local and state officials explained them as suicide or accident, sometimes over objections from the NAACP.

Each of the three lynchings in Wise County contained characteristics that mark them as atypical of lynchings across other parts of the South and help explain why they occurred. While Wise County was not free from racial violence outside of the Guynn, Hunt and Woods lynchings, the spikes in violence associated with those specific killings can be partly explained by other crimes alleged to involve blacks before and after the lynchings as well as the influx of workers moving into the area seeking employment. Two of the victims, Guynn from NC and Woods, from Pittsburg, were recent arrivals, who had come to work in the mines. David Hunt’s origins are unknown; even his real name is in dispute. Wiley Guynn was the victim of summary justice by a mob probably agitated by extended delays in the case of Robert Foy. In his case, the lynching averted may have created the conditions for Guynn’s killing. Dave Hunt was lynched probably because Sheriff Corder failed to receive timely notice of the mob’s intentions. The lynching of Leonard Woods occurred in Virginia by accident; the sheriff of Jenkins told the mob to go elsewhere, and the existence of the platform just across the border seemed a suitable location. The sensationalism surrounding the Woods case, and the conflicting accounts of what really happened, pushed the Governor and legislature of Virginia finally to take action against the horrid practice. Thus while the three Wise County lynchings occurred over a span of years and exhibit characteristics common to lynchings elsewhere, each had its own additional circumstances that show the real lack of justice for African-Americans. The Wise County lynchings present us with a case study of how local circumstances affected racial violence in the early twentieth century.

Zoe Crihfield is a junior history major at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise. She is in the history honor society, Phi Alpha Theta, serves as Student Government Association Vice President, and is an Early College Academy history mentor. Her historical interests include 20th century American history, Appalachian studies, and Women’s history. She plans to attend graduate school following her time at Wise.

Tom Costa (tmc5a@uvawise.edu) is professor and chair of the Department of History and Philosophy at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise, where he has taught since 1992. Trained in early American history, he directs the website “Geography of Slavery in Virginia“. He is currently working with a team memorializing lynchings in Wise County. This essay is the product of their research.

Dylan Mabe is an English and History major at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise. He is from Big Stone Gap, Virginia, and a member of the Phi Alpha Theta and Sigma Tau Delta. He spends his time reading and writing science fiction.

Thomas Noble is a high school history teacher and lives in Southwest Virginia and can be contacted at tnoble2945@gmail.com. Thomas graduated from the University of Virginia’s College at Wise in 2019 with a degree in History and Philosophy and a minor in Secondary Education.

What is the source of that brutal photograph of the Woods lynching scene? Are there any identification made of the white men in the photo?