By JIM HALL

Charlotte Harris was lynched near Harrisonburg, Va., in 1878. A news story described how a group of disguised men stormed the place where she was confined, took her from a guard, and carried her away. The men dragged Harris about 400 yards to the Gilmore place. They bent a blackjack oak sapling and tied a rope from it to her neck. “In another instant the tree was let go and the victim was jerked into midair,” the story said.

A similar abduction and death happened in 1889, when 100 men entered the jail in Leesburg, Va., and seized Owen Anderson. Like Harris, Anderson was black and had been accused of a crime, but he had not been tried. The men took him to a rail yard nearby and hanged him from a derrick. “After hanging him, they fired a number of bullets in his body and rode away,” the story said.

This website, Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia, 1877-1927, contains the names of more than 100 lynch victims. More than 500 news stories accompany the list and describe how the victims died. The stories are detailed and often horrific–the bent sapling or suspended body–yet they give meaning and certainty to each death. Victims are remembered; murderers stand exposed.

Such was not the case for Shedrick Thompson, a 39-year-old black man who died at the end of a rope in 1932 in Fauquier County. An angry mob set fire to his corpse and took body parts as souvenirs. But his death was not reported as a lynching. Instead, county officials told reporters that Thompson had killed himself. Rather than be captured on an assault charge, they said, he put a rope around his neck and jumped from an apple tree.

Thompson’s death came near the end of the lynching era. Nearly three-fourths of the victims included in this website died earlier, before the turn of the 20th century. For black Virginians, these years, from 1880-1900, were the deadliest of the period. A lynching occurred about once every three months. Many of these lynchings took place in daylight and in public. They were often advertised in advance and attended by large groups of the curious. Historians have described them as community spectacles, similar to religious rituals of sacrifice. And those responsible were almost never held to account.

But that started to change after the turn of the century, as Virginians and others throughout the South acknowledged the risk to all from this chaos. Lynchers could no longer count on community support, so in the words of historian Philip Dray, they went “underground.” Lynching became a private affair, carried out by small groups of determined men who killed their prey, then walked away, never to brag about what they had done or read about it in the newspaper.

The League of Struggle for Negro Rights, a civil rights group, noted this when it included Thompson in its annual list of lynch victims. “There was a definite attempt [in 1932] to cover up many lynchings,” it said. “In many cases, the lynchers did their work quietly and discovery was made only much later.” The Tuskegee Institute and several other groups, including the Federal Council of Churches, the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, and the Associated Negro Press, joined the League of Struggle in listing Thompson among the nation’s lynch victims in 1932. After years of research for my book about the case, I reached the same conclusion, that the evidence in the Thompson case points to lynching and not suicide. Prior to publication of the book, I forwarded information about the incident to the Equal Justice Initiative. Based on the facts of the case, EJI included Thompson on its national memorial to lynching victims, which opened in 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama.

In 1932, however, the official record had another spin. Documents in the Fauquier County Circuit Court in Warrenton describe Thompson’s death as a suicide. Former Virginia Governor Harry F. Byrd believed in the suicide verdict and lobbied to preserve what he believed was Virginia’s lynch-free reputation.

Thompson’s death posed a dilemma for Byrd, both personally and politically. Byrd lived in Berryville, about 40 miles from the Fauquier home of Henry and Mamie Baxley, the couple Thompson was accused of attacking. He was friends with the Baxleys, grew apples as they did, and liked to visit their farm in Fauquier to hunt quail. In addition, Henry Baxley was chairman of the county Democratic Party and supported Byrd in his many campaigns. Byrd seemed genuinely concerned about the Baxleys after the attack and wrote to Henry several times while the couple was in the hospital. But the attack and eventual discovery of Thompson’s body also challenged Byrd politically.

Two weeks before the attack, Byrd was in Chicago at the Democratic National Convention. He was a contender for the party’s presidential nomination and received votes on the convention’s first three ballots. The party eventually nominated Franklin Roosevelt. Byrd’s ascension to the national political stage was based in part on his reputation as the architect of the nation’s strictest anti-lynching law. Virginia had experienced a spate of lynchings in the 1920s, including two particularly vicious incidents while Byrd was governor–the Raymond Bird case in 1926 and the Leonard Woods case in 1927. Byrd felt powerless to deal with what was seen at the time as a local matter. Under pressure by journalists like Louis Jaffé and other anti-lynching activists, Byrd persuaded the Virginia General Assembly to pass legislation in 1928 to make lynching a state crime.

Byrd and Virginia enjoyed positive publicity after the passage of the bill. The legislation also was seen as a boost to the state’s business recruitment efforts. But as historian J. Douglas Smith has pointed out, state officials “recognized that the law needed to be seen as effective. To this end, they insisted that Virginia never suffered another lynching after passage of the act, a claim that occasionally flew in the face of common sense.” Byrd’s reaction when the NAACP included Thompson on its 1932 lynch list illustrates this point. Byrd wrote to Walter White, head of the NAACP, and asked his friends to do the same. Byrd claimed that Thompson committed suicide, though he offered no proof. White at first resisted the idea, then relented under pressure and created a new category for Thompson, that of a “hairline case.” The group’s decision gave comfort to Byrd and his associates. For them, Thompson would not be a blemish on the state’s record.

Shedrick Thompson grew up in Fauquier, the third of nine children born to Fannie and Merrington Thompson. Like his father and older brother, he was a laborer, helping tend the fields and orchards of northern Fauquier. When the U.S. entered World War I, he was drafted into the Army, trained in Arkansas and shipped to France to serve with other “colored” troops. After the war, he was honorably discharged and returned to Fauquier. He married and resumed his life as a farmhand.

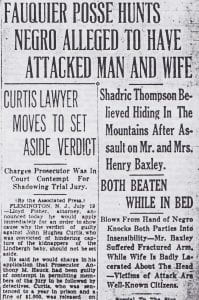

On a hot summer night, July 17, 1932, Thompson sneaked into the home of his employers Henry and Mamie Baxley and attacked them. Thompson had worked for Henry and his father for 15 years. Thompson’s wife Ruth was the Baxleys’ cook, and the two families lived next door to each other. Motivated by some unexplained fury, Thompson slipped into their bedroom, armed with a piece of stove wood from the kitchen. He beat Henry Baxley unconscious and forced Mamie Baxley from her bed, out of the house, to a field nearby. There he raped, beat and robbed her. The Baxleys survived the attack, though Mamie Baxley spent a week in the hospital.

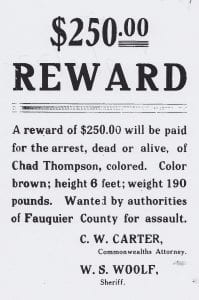

Thompson, meanwhile, fled into the mountains of northern Fauquier where he grew up. Soon posses, both authorized and volunteer, took to the hills to capture him. Hundreds of armed men, on foot and horseback, spent days marching the rocky paths but could not find him. Eventually, the men abandoned their search and returned to their fields and chores. Thompson’s name slipped from the headlines.

Nearly two months later, on Sept. 15, 1932, a tenant farmer, checking his fences to see why his cattle were getting out, found the body of a black man suspended from an apple tree. The site was three miles from the Baxley home in a thicket on Rattlesnake Mountain. It was the body of Shedrick Thompson.

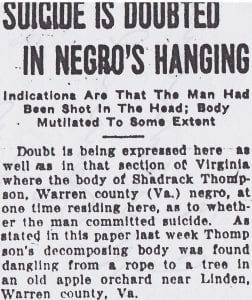

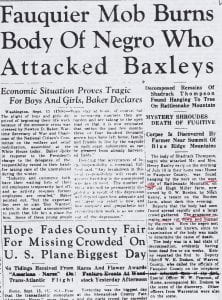

The discovery was front-page news in local and regional newspapers. Accounts described how the farmer called authorities to report his discovery, but Sheriff Stanley Woolf was in Warrenton 20 miles away. Before he could get there, a mob gathered and set fire to Thompson’s body. Woolf’s deputy, W.W. Pearson, arrived and tried to beat out the flames with his new hat. Years later, Pearson’s grandson, Melvin Poe, remembers his grandfather saying that someone stopped him by placing a pistol in his ribs. “Let it burn,” the man said. When the fire was done, all that was left of Thompson were his skull and his shoes. The county coroner ruled that night on the mountain that Thompson killed himself rather than face capture. A grand jury confirmed the verdict, adding that it could not identify those responsible for the destruction of the body.

Fauquier authorities may have hoped that the suicide verdict would bring a quick end to an embarrassing affair. But local residents recognized it for what it was–a rush to judgment and contrary to common sense. Soon, local and regional newspapers joined in the criticism. “Suicide is doubted in negro’s death,” said one headline. “Suicide is now synonymous with lynching in Virginia,” said another. A third paper called for a new investigation into Thompson’s death, pointing out, “An individual eluding arrest could not have found the time to locate a piece of rope” to hang himself with.

Thompson’s death bore many similarities to the lynchings that came before. Like other incidents, his case began with the allegation of a violent crime—the beating of a white man and the sexual assault of a white woman–that led to a response from private posses. As in other cases, the posse captured, tortured and executed him, then after death defiled the body and took body parts as souvenirs. And as with most lynchings, those responsible were never indicted, convicted or imprisoned.

Arthur Raper, a sociologist, studied the rise in the number of lynchings in the 1930s and described it in a 1936 paper entitled The Mob Still Rides. Raper counted 84 lynchings nationwide from 1931 to 1935. He said that the typical lynching during this period included a black victim and took place in a poor, rural Southern community, with those responsible being native-born whites. He included Thompson in his tally.

The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, an Atlanta-based group, also included Thompson in its tally for 1932. In addition, the organization said that if a black man died under mysterious circumstances in the rural South, it felt justified in thinking of the event as a lynching. In other words, given the time and place, if it looked like a lynching, it probably was.

Today, many Fauquier County residents, both black and white, including some who were alive at the time, believe Thompson was lynched. Henry Baxley Jr., who was an infant in the house when his parents were attacked, said, “It was never ruled a lynching, but everyone knows it was.” Jeff Urbanski, whose great-uncles are most often mentioned as leaders of the posse who caught and killed Thompson, said he doesn’t condone what happened, but family lore is that, “he did the act, he hid in the mountain, he was caught, the mob took care of him, and walked away from it.” And Sylvia Gaskins, whose father, Guy Jackson, was Thompson’s best friend, said, “They caught him and burned him and castrated him up there in that orchard.”

Historians estimate that nearly 4,000 people were victims of racial terror lynchings in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They also agree that this estimate is certainly an undercount. Many others suffered similar fates, but their deaths went unreported at the time, their names unmentioned in official tallies. Thompson is sometimes included in this group–a hairline case, as the NAACP said. But he does not belong there. He was no doubt guilty of assaulting the Baxleys, but he was also the victim of a crime. He was hunted and hanged by his neighbors on Rattlesnake Mountain, a Virginia lynching.

Jim Hall is a resident of Fredericksburg, Va., and a retired newspaper reporter and editor. His master’s degree work at Virginia Commonwealth University included a study of how Virginia newspapers covered lynching. He is the author of a nonfiction account of the Thompson case, The Last Lynching in Northern Virginia: Seeking Truth at Rattlesnake Mountain, published by History Press in 2016.

Interesting article, but how does one really know if Shadrack Thompson was guilty of any crime. Mr. Shadrack Thompson’died a horrific death in 1932, void of his due process rights. He had a story and it remains with the mob of muderers on Rattlesnake Mountain. I am thankful that the cover-up of the lynching was revealed.

Hello that was my Great Uncle, my grandma told me this story several years ago and it hurt my soul to know that a person in my family had endured part of that wretched and disgusting history. Its hard for me to believe an honorably discharged man would come back and randomly attack a couple he considered friends without a serious cause, but the truth will nver be found out because all parties are no longer with us. But thanks for the article, a very interesting read

Thanks for this information, Shedrick Thompson was my great uncle and it is very sad to know that I have this haunting and disgusting history in my family. While I disagree with there take on what happened , it can’t be proven now. Thank you for this article because it verified what my grandma had told me years ago.

Hi Eve,

My Grandfather was 12 in 1932. I heard the story from him, and he described it as having a clear motive: Henry Bixly Sr. was raping black women in the community. I assume that he discovered someone he knew was a victim and sought justice, but that part is my own interpretation only.

I was also told that the men found him quickly after the assault, and shot him. The community then worked together to cover the murder.

I didn’t know until today that this was a cold case, and have spent the evening reading the information available online. I don’t know if this secondary information is useful or useless, but since I hadn’t seen a possible motive listed in any article, I wanted to provide what I heard. Unfortunately my grandfather died this year, and I don’t recall much more.

I’m sorry for what happened to your great-grandfather.