By JIM HALL

Richard Sanderson watched from his hotel window in August 1888 as twin columns of armed men, nearly 40 in all, galloped below on Main Street in Farmville, Va. Soon the men were out of sight, and all was quiet until shots broke the stillness. Sunrise brought an explanation for the strange sights and sounds of the night before: a black man was hanging from a tree at the edge of town.

From his room at the Prince Edward Hotel, Sanderson had witnessed the start of the lynching of Archer Cook. What he could not see from his vantage point was how the riders breached the walls of the county jail, dragged Cook from his cell, drew him up, and filled him with bullets. Sanderson, 30, was in Farmville to represent his employer, the Norfolk and Western Railway. He was as an assistant superintendent for the rail line and traveled often from his home in Roanoke, Va., whenever the company faced a claim for damages in a county court. He also recorded in his memoir what he saw and heard of Cook’s murder, a rare eyewitness account of a Virginia lynching.

Historians have long relied on newspaper stories, rather than personal accounts like Sanderson’s, to learn about lynchings. My study of lynching coverage, however, shows that most accounts that appeared in Virginia newspapers during the lynch era, 1877-1932, were usually written after the event occurred and thus lacked the power of an eyewitness telling. As a newspaper reporter and editor for 36 years, I can imagine how a reporter in Farmville, Roanoke or Charlottesville at the time might arrive for work to learn that a lynching had occurred overnight. I can see the reporter interviewing people, visiting the scene, doing as much as he can, as fast as he can, to write a story on deadline. At least that’s how these stories read today: workmanlike accounts that answered the obligatory questions of who, what, where, when and why. The stories, from Southern, white-owned papers, often described black victims as impulsive, dangerous and guilty as charged. Racial epithets, such as brute, demon and ravisher, were common. When shocking cases occurred, such as the 1885 murder of 12-year-old Alice Powell in Princess Anne County, Va., the stories took on a more ominous tone, describing the “intense” sentiment in the community and “strong talk” of lynching. After Noah Cherry was charged with the young girl’s murder, The Norfolk Landmark told readers, “It is to be hoped, and, we may add, it is to be prayed, that the brute who perpetrated it be made to undergo the full measure of punishment.” The next day a mob stormed the jail where Cherry was being held and hanged him. (Norfolk Landmark, November 15, 1885, page 2)

Black-owned newspapers opposed this lawlessness, and none stood more fiercely than The Richmond Planet and its editor John Mitchell Jr.. A former slave, Mitchell was named editor of the weekly paper soon after its founding in 1884 and served for more than 40 years. Mitchell wrote dozens of editorials opposing lynching, ran photos of incidents, and kept a running tally of lynch deaths. He called on state and local officials to enforce the law and end this “barbarity.” His long-running opposition earned him the title “The Fighting Editor.” Mitchell did little original reporting when a lynching occurred, instead copying the stories that appeared in the white dailies. But he did print letters from local residents, or correspondents who knew of details that contradicted the accounts in the white papers. For example, a black lynch victim accused of assaulting a white woman was actually the woman’s lover, a letter-writer might report. With these details, Mitchell tried to put readers at the scene and show them that lynch victims were human beings who had been denied the protections of the law and their God-given right to life.

Ironically, it was in these instances that Mitchell’s coverage resembled the stories from the white dailies when their reporters were eyewitnesses to the mobs’ murders. In eyewitness accounts, the reporters abandoned the expected racial narratives in favor of ones that were rich in detail and, at times, even sympathetic. Victims were no longer “ruffians” or “darkies.” Instead they were frightened young men, facing imminent death. It was as if the reporters understood the enormity of what they were seeing and tried to bear faithful witness to it.

Take the account of Joseph McCoy’s death in Alexandria in 1897. A reporter for the Alexandria Gazette witnessed the mob’s attack on the city jail, where McCoy was being held on an assault charge. He described how McCoy was “terribly frightened.”

“McCoy had climbed up on the door and was secreted near the ceiling. The mob believed they were in the wrong cell, and were about to leave for another, when one of McCoy’s legs was discovered. He was pulled down with a yell and dragged to the pavement and the mob surged toward Cameron Street with him.”

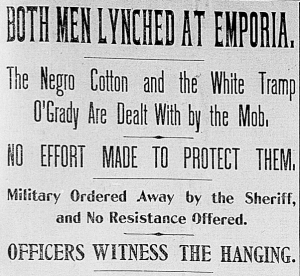

Similarly, a reporter for the Richmond Dispatch painted a vivid picture of the lynching of accused murderer Walter Cotton in Emporia in 1900:

“Just in front of the courthouse was an old sycamore tree which had a branch growing from its trunk at right angles about 20 feet from the ground. To this the negro, numb from the effect of his shackles, was dragged, and two young men started to climb the tree to adjust the rope over the limb. One fell back, however, and the other being boosted by those on the ground soon reached the limb. It was but the work of a moment for him to toss the rope over the limb, and then someone cried, ‘Everybody catch hold of the rope.’ In a second Cotton was drawn up to the limb of the tree, his forehead being badly gashed by a protruding limb.”

And in Roanoke in 1893, a reporter for The (Richmond) Times was present to describe one of Virginia’s most gruesome lynchings, the death of Thomas Smith. He reported that the mob hanged Smith, then cut down the body, loaded it on a coal cart and carried it to the banks of the Roanoke River. There they tore down fences and used the planks to build a funeral pyre. They added dry cedar boughs and doused the pile in kerosene. He continued:

“A lighted match was applied, and the body was soon enveloped in flames. When the fire burned low, more plank was thrown on. When a member of the body became separated from the rest, it was pushed back with a pole. This performance was kept up until all that remained of Thomas Smith was a small pile of ashes.”

Sanderson, too, was a careful observer that night in Farmville. He recorded what he saw in an unpublished memoir, now in the possession of his great-grandson, the Rev. Peter Getz of Rockwall, Texas.

“I heard horses come clattering along the street. Mounted men came along two by two, dropping a guard at each cross street intersection, the main body went on to the courthouse. There was some banging and battering, then the procession returned in like manner, and all was quiet till I heard a rattle of shots.”

That year, 1888, saw similar Virginia mob deaths in Wythe and Halifax counties. The next year, one of the deadliest on record, saw lynchings in Accomack, Russell, Halifax, Nottoway, Charlotte, Tazewell, Loudoun and Prince George counties. In all, more than 100 people were killed in lynchings in Virginia, among the thousands who died in the old Confederacy in the years before and after the turn of the 20th century. Little is known about Archer Cook, though news reports at the time described him as black, 22, and married. In July, two months before his death, he was arrested and placed in the county jail in Farmville, accused of the rape of Miss Lizzie Frank. Frank was said to be a “highly respectable young lady.” She was white, of German parents, and lived in Rice’s Depot, a crossroads east of town. News stories did not give her age or say whether she knew Cook. They also were silent on the possibility that their relationship was consensual. Instead, reports described her as “unfortunate,” and the incident as a “brutal” and “fiendish” assault. The alleged rape of a white woman by a black man was the second most frequent cause cited in lynchings, after murder. Mobs also used the accusation to punish voluntary interracial affairs.

W.E.B. DuBois, one of the founders of the NAACP, mentioned this possibility in Cook’s case. Writing in 1898 in his famous sociological study The Negroes of Farmville, Virginia about the Farmville lynching, DuBois said, “It is now generally conceded that the female was a lewd character, and the black boy was guilty of no crime.” Lizzie Frank’s behavior after Cook’s arrest added to this speculation. Authorities postponed Cook’s trial several times because Frank was said to be too sick to testify. Was she truly ill, or did she seek to avoid a court appearance? She must have known that her testimony would spell certain death for him if they were lovers. In any event, the members of the lynch party believed that Cook, in the words of The Washington Post, “would escape justice by some technicality of the law,” so they decided to act. At the jail that night, the lynchers were “fearless and furious,” said one report, as they broke through the brick walls. Inside his cell, Cook “screamed piteously,” but the men removed him and rode away. Authorities apparently did not try to defend their prisoner or the jail. The men hurried Cook to the nearest woods and hanged him from an oak tree, his feet barely touching the ground. They fired 25 shots at him, then galloped off, “leaving a terribly mangled corpse.”

In many ways, Cook’s hanging in Farmville was typical of the grim rituals that grew up around lynching. He was black, as were 90 percent of lynching victims. His death was apparently well planned and occurred in a public place, indicating a measure of community support. And, as it was typical, no one was ever charged with the victim’s murder, or with the damage to public property, in this case the county jail. In their coverage of the event, local newspapers described the lynchers as honorable, even admirable, men. One story praised them as “orderly and quiet,” and said they “came and went with almost military precision.” Added The Richmond Dispatch, “There are no more law-abiding people in the land than these hereabouts. Nothing less than almost positive evidence of guilt could have dictated this course.”

The reasons given for murdering Cook were also familiar. The lynchers did not trust the existing criminal justice system, news stories said. Cook had been in jail for two months, proof to them that the courts were slow and unreliable. Their punishment was swift and certain. Mob members also saw themselves as defenders of the white community, especially white women. Sanderson learned of this from one of the riders. He recorded in his memoir that he recognized one of the men as a railroad employee. Later, “at a suitable occasion when we were alone,” he talked to the man.

“Why not let the law take its course?” he asked.

“If it had been your wife, would you have been willing to have her openly state in court how she had been brutally abused?” the man replied.

What distinguishes Sanderson’s account and the other eyewitness stories are the details, almost cinematic in their power. We can see McCoy hiding on top of his cell door, the riders in Cook’s case peeling away to guard the cross streets in Farmville, and Cotton’s gashed forehead on the sycamore in Emporia. These details allow readers, then and now, to better understand what mob rule really looks like.

Jim Hall is a native of Virginia, a resident of Fredericksburg, and retired after a 36-year career as a newspaper reporter and editor. He studied lynching coverage by Virginia newspapers while earning a master’s degree at VCU. His nonfiction book about the 1932 lynching of Shedrick Thompson in Fauquier County, Va. The Last Lynching in Northern Virginia: Seeking Truth at Rattlesnake Mountain, was published by History Press in 2016.