By Tom Blair

On February 28, 1878, a barn burned in Rockingham County, Virginia. The event was reported by both of the newspapers operating at that time in the county seat of Harrisonburg. For the most part, these accounts read like insurance reports, giving dry details about the barn’s contents, the estimated value of the loss, and the amount insured by the East Rockingham Fire Insurance Company.

Some aspects of these stories, however, struck a different tone. The Rockingham Register categorically stated that the fire was the “diabolical” work of James Ergenbright, a 17-year-old African American, and that he had been induced to set the fire by “a colored woman named Charlotte Harris.” The Old Commonwealth reported that Ergenbright was in custody and that Harris was being pursued by officers of the law. “It is to be hoped,” the Register wrote, that the officers “have secured her.”

By the time these articles were published on March 7, 1878, their reporting was out of date. Charlotte Harris already had been “secured” and was hanging from a tree. Her body would remain there for two days, suspended near a roadway in East Rockingham, for viewing by all who passed.

***

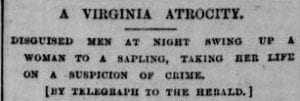

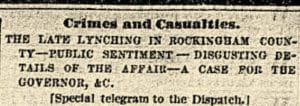

The next editions of the local papers were not published until a week after the lynching. In the meantime, the news spread across the country. Headlines appeared within days – in Richmond, Washington, Wheeling, Philadelphia, New York, Indianapolis, Chicago, and Kansas City – telling of “The Lynching of a Woman,” “A Virginia Atrocity,” and the “Disgusting Details of the Affair.”

The initial coverage from national and local sources agreed on many of the facts. According to these articles, the barn in question belonged to Henry Sipe, a prosperous white farmer who lived a few miles east of McGaheysville. After the fire, Ergenbright (whose name was also reported as Argenbright, Arbegast, or Arbegart in some accounts) was taken into custody and confessed. He also implicated Harris, who was said to have harbored a grudge against the Sipe family, as having induced him to set the fire and then fled across the Blue Ridge mountains.

A group that included two constables set off in pursuit. They found Harris at a home near Earlysville in Albemarle County, where they arrested her and brought her back to the Sipe farm in Rockingham. Harris was at once taken before the magistrates for a preliminary hearing, which resulted in an order that Harris would be taken to the county jail in Harrisonburg. The hearing was attended by an excited crowd of about 100 people (Rockingham Register, 3/14/1878; Old Commonwealth, 3/14/1878).

Harrisonburg was over 15 miles away, and the officers decided to wait until the next morning to make the journey to the jail. That night, at around 11PM, men with their faces darkened appeared at the outbuilding where Harris was being held. These men entered the building with pistols drawn and were joined by a larger group of people who were also armed and disguised as “colored men.” The mob seized Harris and dragged her about 400 yards up the road until they reached a blackjack oak tree. (Richmond Dispatch, 3/11/1878; Staunton Spectator, 3/12/1878; Rockingham Register, 3/14/1878; Old Commonwealth 3/14/1878; Rockingham Register, 5/23/1878).

According to multiple accounts, the tree was a large sapling that was particularly tough. Five men applied their strength to bend the tree over. After tying a rope to the tree and looping the other end around the neck of Harris, they suddenly let go of the tree. At that point, in the words of one account, “the shrieking female was jerked up into the air with frightful velocity.” Harris was pulled upwards as the sapling sprang back and she landed on the other side of the tree, which the mob propped up with a fence rail. Harris hung there, struggling in great agony, until she was dead. (New York Herald, 3/10/1878; Richmond Daily Dispatch, 3/12/1878; Kansas City Daily Journal of Commerce, 3/13/1878; Rockingham Register, 3/14/1878).

From the time of her death on the night of Wednesday, March 6, Harris’ body was allowed to remain dangling at this spot, in prominent view on the roadside, for nearly two days. Not until the afternoon of Friday, March 8, was the body cut down and buried (Old Commonwealth, 3/14/78).

***

When the Rockingham Register first reported the lynching on March 14, it expressed formal disapproval laced with rationalizations. The paper said “[w]e regret exceedingly that the good people of East Rockingham thought proper to resort to such summary proceedings.” It speculated that tempers had been inflamed by the injuries inflicted on “a prosperous and peaceable citizen.” It expressed sympathy for the populace while urging them to allow the courts to deal with such matters in the future. The Old Commonwealth offered similarly tepid comments. It observed that barn burning was not a hanging offense and that the lynchers had acted “hastily and without proper consideration.” Nevertheless, the paper said, it could understand why the citizens of East Rockingham would want to rid themselves of those who committed such crimes.

Notably, neither of these articles carried comments from any local or state officials. When reporters called on Virginia’s Governor, Frederick W.M. Holliday, to ask what action he intended to take, he said that he had not been officially notified of the incident. Not until March 15, more than a week after the lynching, did the Governor issue a proclamation offering a reward of $100 for the arrest and conviction of each of the perpetrators.

All the while, newspapers outside of the Shenandoah Valley eagerly covered the story. This coverage, particularly in the northern and mid-western press, was often filled with strong condemnation. Under a headline of “What Is the Matter in Virginia,” the New York Herald asked “how could it be possible that there is any excuse for the practice of this kind of barbarity in Virginia?” Indiana’s Greencastle Press stated that if “the people in some parts of the South would show a little less fury towards colored criminals and a little more justice towards white ones, we would have more reason to commend them.”

Other papers were more direct. Vermont’s Green-Mountain Freeman wrote that “[i]t was a fiendish murder, and nothing short of it.” The Iola Register in Kansas angrily stated that “[a]bout one hundred persons are supposed to have been engaged in this little piece of Southern pastime. Verily, some of these F.F.V.’s are a chivalric set of villains, when they string up a woman with less humanity than a cur dog is entitled to.” The Washington National Republican sarcastically wrote that a “party of high-toned, chivalrous Virginians lynched a colored woman down in Rockingham County last week because circumstantial evidence indicated that she had advised the incendiary burning of a barn. But you know the State is bankrupt, and it’s cheaper to murder a suspected criminal than go to the expense of a trial. Besides as many as two horses and two cows lost their lives in the destruction of the barn.”

Although some papers praised Governor Holliday, the Daily Press of Portland, Maine was not impressed. “It is safe to say,” it predicted, that the Governor’s reward would never be claimed. “Anyone who claimed it would be lynched himself. The arrest of negro-killers is not popular down there.”

A few correspondents made bizarre claims about the area. A reporter for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat wrote that Rockingham County was one of the “wildest and most uncivilized in Virginia” and many of its inhabitants are “almost barbarians.” He portrayed the lynching as “but another leaf in the calendar of lust and lawlessness of the God-defying and law-breaking denizens of the rocky crags of the Alleghenies, many of whom live in the caves and huts.” In a similar vein, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “[t]he country is mountainous and wild and the inhabitants […] are said to thirst for blood.”

***

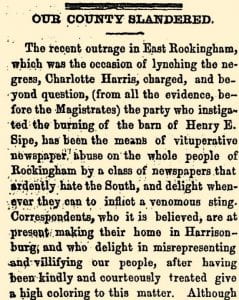

Such criticism caused the local papers to abandon even the mild disapproval initially expressed after the lynching. Instead, they became defensive, taking the line that the true victim was Rockingham County. The Rockingham Register on March 21 ran an article entitled “Our County Slandered” decrying the “vituperative newspaper abuse on the whole people of Rockingham by a class of newspapers that ardently hate the South, and delight whenever they can to inflict a venomous sting.” The Register complained that “[w]hilst but a small portion of our county was engaged in that deplorable affair,” the “whole people are blamed and such shameful and abusive language is used.” Rockingham, the Register argued, was a place of law and order whose record was as clean as “any county of like size in the North or West where emanates these wholesale slanders.”

The Old Commonwealth joined the chorus. It extolled the virtues of Rockingham’s people (“unexcelled for thrift and energy”), education (“pretty generally diffused”), soil (“equal to any found anywhere”), climate (“healthful and invigorating”), and scenery (“noted for its beauty and picturesqueness” with “lowing herds of fine cattle and flocks of the best breeds of sheep”). It asserted that “[n]o community […] should be defamed for the acts of violence of a few. It is unjust, unfair.” The paper claimed that officers of the law were busily looking for clues to find the guilty parties.

From that point forward, the Register adopted an increasingly aggressive and mocking tone. It ran a short piece entitled “A Bad Woman” stating, without referring to any supporting source, that “[b]eyond question Charlotte Harris […] was a bad woman.” It claimed that Harris “formerly belonged to Geo. Loflin, whose family she attempted to poison. She also threatened to burn the barn of Wm. B. Yancey and would doubtless have carried her threat into effect but for her career having been cut short by Judge Lynch’s gang.”

***

The investigation of the grand jury into the murder of Charlotte Harris concluded in early April without indicting anyone. This result was greeted by the Old Commonwealth with only a short notice that expressed no surprise or concern. Characteristically, the Register had more to say. After praising Judge Charles T. O’Ferrall for supervising the grand jury, the Register proclaimed that “[i]t seems very probable now that only half a dozen persons were engaged in the work, and these may have come from the ‘Mountains of the Moon,’ or some other foreign country. It is quite evident that they were not citizens of Rockingham, or some witness would have testified to that fact. Strange, is it not?”

***

A few weeks later, James Ergenbright was tried on a charge of arson. This trial took place in Harrisonburg in the court of Judge O’Ferrall. Surprisingly, when the jury verdict was returned, Ergenbright was found not guilty. Likewise surprising was the lack of immediate discussion in the local press of the reasons for the verdict.

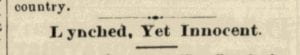

Outside of the Valley, however, this verdict ignited a new round of coverage. Headlines of “Lynched, Yet Innocent” appeared in many papers. “Alas, for Virginia” declared the Chicago Tribune. “It turns out that the negro woman who was hanged by a mob of chivalrous Virginians […] had actually nothing to do with the crime.” An Ohio paper reported that Virginians had hung Harris “and now find that she was innocent. But then, Charlotte Harris was not white, and what is the difference: they had their fun.” A Colorado paper expressed its view of the situation as follows: “[t]hey hanged the poor woman because she was black.”

This turn of events provoked further fury from the Rockingham Register. The paper, together with others in the Valley, attacked the idea that Ergenbright’s trial had exonerated anyone. The Martinsburg Statesman lamented that “[l]achrimose tears have been shed over the lynching of a negro.” The article argued that Ergenbright had escaped conviction on a legal technicality and that his acquittal did not prove the innocence of Harris. It pronounced itself satisfied that Ergenbright was in fact guilty and that he had acted either at the instigation of Harris or “from genuine African deviltry.”

The Register ridiculed those who referred to Harris as innocent. It rhetorically questioned “when Charlotte Harris had a trial and been declared innocent.” It sarcastically asked if “Charlotte has been heard from by means of the grape-vine underground telegraph.”

***

On May 4, 1878, the editor of the Martinsburg paper wrote to Judge O’Ferrall for further explanation of the case. O’Ferrall responded with a wide-ranging commentary revealing that Ergenbright had been taken after the fire to the constable’s own house and subjected to questioning that lasted during the night and into the next morning. Ergenbright initially denied burning the barn. Then, as the questioning continued, he asked whether Sipe (who employed Ergenbright on the farm) would pay “the money due him” if he confessed. The officer replied that “if you will confess, he will be bound to pay you.” At that point, Ergenbright confessed and implicated Harris.

O’Ferrall further revealed that, when Harris was brought before the magistrates, the sole evidence against her had been Ergenbright’s confession and “some vague statements of threats against Sipe upon the part of the woman.” At Ergenbright’s trial, the only evidence against him had been his confession, which was excluded on the ground that the officer had offered him inducements to confess. O’Ferrall concluded that “I have very grave doubts as to the guilt of the woman,” emphasizing that Harris could not have been convicted upon the testimony against her. He added that many people in the neighborhood believed her to be guilty based on their opinion that she had a “general bad character,” but that others believed Ergenbright had concocted the story for his own advantage. The judge concluded by saying that the truth would probably never be known for certain, and his statement that Harris was innocent was an assumption on his part.

The Martinsburg paper seized on O’Ferrall’s last statement to proclaim that the “terrible story […] of an innocent women ‘ruthlessly dragged from home’ is not borne out by the facts.” Harris, it argued, should not be referred to as innocent. After reprinting this assertion with evident approval, the Rockingham papers seemed to hope that there would be no further discussion of Charlotte Harris. Her name did not appear again in their columns.

***

But Charlotte Harris was not forgotten. 18 months later, her name was raised on the floor of Virginia’s General Assembly. R.L.G. Paige, an African-American delegate, introduced a resolution asking the governor to offer a reward in connection with two recent lynchings in Amherst and Warrenton. He argued that the law should be allowed to take its course, rather than having killings by mobs infuriated by whiskey. According to the Petersburg Index-Appeal, Paige told the assembly that “Charlotte Harris, a negro woman who was lynched last year in Rockingham, was innocent of the crime for which she had been hung.”

In response, William Henry Fitzhugh Payne of Warrenton (a former Confederate Brigadier General) rose to dispute Paige’s description of the Warrenton lynching. He claimed that the lynched man had seduced a white woman. Payne continued by saying “[w]hilst I strongly condemn mob law, yet when such a thing as that happens I will turn my back and shut my eyes for a few minutes whilst the operations are going on.” (Petersburg Index-Appeal, 1/22/1880).

Payne moved to refer the resolution to committee for study, a motion which passed by a wide margin. The next day, the Index-Appeal praised Payne’s speech as “succinct, fearless and manly” and reported that all but two of the white delegates voted with Payne. The paper commented that this occasion was the first time in the session when the white members of the two opposing parties had agreed on anything.

This debate may have been the last time that the name of Charlotte Harris was spoken publicly for well over a century. Her death was invoked to protest the ongoing killing of citizens without due legal process. The response of the “fearless” lawmakers, however, made clear that they would do little to prevent future lynchings.

The years ahead would, in the words of General Payne, be filled with more turned backs and more shut eyes.

Tom Blair is a native of Rockingham County who developed a lifelong interest in Virginia’s history while attending school in Harrisonburg and at the University of Virginia. He currently works as an attorney in Washington, D.C. and can be contacted at ctomblair@gmail.com

Northeast Neighborhood Association to memorialize Charlotte Harris in Harrisonburg

https://www.whsv.com/content/news/NENA-to-memorialize-lynching-victim-in-Harrisonburg-508298331.html?fbclid=IwAR2DJG2yUlknAOJy0rQv1cx9j0yAUPv8jfDoMPrEiO0AKIWj4uPdGEMdDzo

Important work you are doing. Thank you.

It is important to have a fuller telling of history so that the marginalized are not invisible to the masses. In the spirit of the “Say her name” efforts prompted by Dr. Kimberly Crenshaw we should uplift the story of Charlotte Harris among the mostly unnoticed black women harmed in this country recognizing that their invisibility is often a product of the intersections of their identities that devalue black women bodies and herstories. I suggest that there is more for us to learn about the Charlotte Harris women of their time and I look forward to standing in witness.

Locals Talk Lynching History (Charlotte Harris) http://www.dnronline.com/news/local/locals-talk-lynching-history/article_ca8fd651-8238-53e1-8188-7ac7333e1e6b.html?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=user-share

I found this essay of Charlotte’s life while seeking more information about her. I saw her name inscribed in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama and wanted to know her story. Thank you for your detailed diligence in sharing. May we never forget…

New historical marker on Court Square tells story of Charlotte Harris’ lynching

https://hburgcitizen.com/2020/09/28/new-historical-marker-on-court-square-tells-story-of-charlotte-harris-lynching/

Would it be possible to organize a #TeachTruth Day of Action near the historical marker at Court Square?

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/pictures-teachtruth-day-action/