This skull is 4 inches by 2.5 inches in actual size.

The Sugar skull we are focusing on for this project is a plastic replica of the Sugar skulls used on ofrendas, or alters, that present offerings to the spirits, on Día de Los Muertos. Dia de Los Muertos is a Catholic holiday celebrated in Mexico on November 1st and 2nd each year (Marchi, 35). These celebrations coincide with All Saints and All Souls Day, and honor the life of loved ones while celebrating death. This Sugar skull is a plastic model that was purchased at Spencer’s Gifts in Harrisonburg, Virginia. It is currently being used as a candle holder by Marissa Scholler, a James Madison University junior. This Sugar skull uses a variety of colors, as do all Sugar skulls, to translate a message to the spirits. The yellow and green accents seen embody unity and the sun, for we are all equal under the sun. The pink is used to show happiness exists in this world for the spirits who are coming over (Incorvia, 2016). Because each skull is made individually, the symbols and designs vary depending on what the families are wanting to convey. In some instances, like the Sugar skull modeled here, the image of a marigold is used around the eyes of the skull in order to convey to the spirits that it is a time for celebration when they pass over (Incorvia, 2016). Sugar skulls during the holiday season of Dia de Los Muertos are traditionally molded by sugar by artisans; however, regardless of the materials being used, this objects style has become iconic in popular culture and maintains the name of a Sugar skull, regardless of the materials it is made out of.

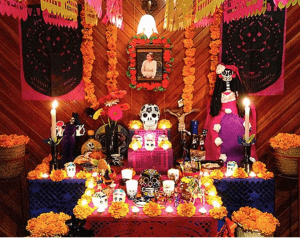

Ofrenda featured in Kettman 2017 article “Day of the Dead Lingo” https://www.independent.com/news/2017/nov/02/day-dead-lingo/

Sugar art as a practice came to Mexico in the 17th century, when the Catholic Italian Missionaries and soldiers entered Mexico along side of Spanish conquerors. The Missionaries set up churches, evangelizing the indigenous people, and introducing new cultural practices and art forms. One of these art forms was sugar art (Villiabla). The Italians had perfected the use of sugar art on Catholic holidays like Easter, creating intricately decorated objects, made of sugar, for children. They used colored icing to decorate the sugar models. This practice was introduced and continued by the indigenous people of southwest and central Mexico, yet the images being cast were altered. During this time, sugar cane was overflowing in the Caribbean and the surrounding land. Explorers from all over the world were coming to the Caribbean specifically for sugar. The natives profited from this natural good. However, Mexican natives did not cast the same art as the Catholic Italians. Instead they created sugar molds based on their fascination with skeletons and death. Skeletons, in both Mexican and Mexican-American folklore embody an afterlife, so life it never truly ending. Death, in this case, is not as scary. Death and the afterlife are embodied by skeletons, which is why they are such evident images in the cultures (Villiabla).

Traditional Dia de Los Muertos Skeletons found in Mexican national costumes playing music to celebrate the holiday. https://depositphotos.com/125792574/stock-illustration-day-of-the-dead-dia.html

Día De Los Muertos was introduced in the United States around the 1890s, but did not make an imprint until the 1960s (Marchi, 34-55). The holiday began to gain momentum in the United States because Mexican-American communities in the South-West began to celebrate openly. Most communities were open to the celebration because it embodied happiness and a celebration that was not associated with the Mexican-American community in the 1950s and 1960s. People outside of the communities were fascinated by the practice of ofrendas and the images being used, which began to shed a more favorable light on Mexican-Americans, as compared to the idea that any person of Mexican descent was dangerous to the communities, or a criminal (Marchi, . Between the 60s and 80s, Mexican-American families began to implement images that were similar to those used around Halloween. This movement started the secularization of once sacred items in Mexican-American culture, including the Sugar skull.

Today, models of the Sugar skulls are common in pop culture as well as the commercial industry, while people do not fully understand its origin. In America, we do not celebrate death. We mourn our loved ones by wearing black clothing and hosting solemn ceremonies. To experience a culture that celebrates death in a more colorful and exciting way causes of an interesting juxtaposition of the two cultures.

The original purpose of the Sugar skull has been lost in American culture. The Sugar skull has transitioned from being an offering and welcoming to the spirits who have passed to a common image in magazines, home decorations, and pop culture. Marissa, much like most people in America with images of Sugar skulls around, does not celebrate Día de Los Muertos. The use of the Sugar skull image is common in the United States because of the secular commercialization of Catholic material that occurred in attempt to modernize the church. This commoditization of religious images and symbols is seen outside of Spencer’s Gifts. These images have fallen victim to popular culture and mass consumption. Unlike other religious images seen in secular stores, the Sugar skull does not fall under Colleen McDannells’ concept of “Jesus junk”. (McDannells, 222).

P. 222 – “Jesus coffee mugs, WWJD bracelets and necklaces, “Smile Jesus loves you” bumper stickers, “This house belongs to the Lord” plaques, various pious bric-a-brac and witness wear…Believe it or not, an industry term for this Christian merchandise is “Jesus junk.” It’s true!”

It has almost been stripped of its religious meaning in this sense because people no longer relate the Sugar skull image or item with a subset of Catholicism, but rather a holiday they do not understand.

Día de Los Muertos sugar skulls in Spencer’s at Valley Mall in Harrisonburg. Taken by: Anna Saunders

Despite the lack of understanding the origin of once sacred items, like the Sugar skull, the images remain constant in the media and popular culture. After years of this presence, and possibly lack of understanding, America has made an effort to understand further the origins and traditions of the holiday of Día de Los Muertos with the new movie Coco, 2017. Coco, by Disney and Pixar, covers all aspects of the holiday after years of research. Disney and Pixar worked hard to understand the meaning of the holiday, instead of simply embracing the skeletons and bright colors for their movie. This is why the movie took so long to produce, because there is more to Dia de Los Muertos than meets the eye. In an interview with Entertainment Studios, screenplay and storyboard artist Adrian Molina had this to say about incorporating the holiday into his work on Coco: “Sometimes, people think it’s like a Mexican Halloween or something spooky or somber when in fact, it’s this moment of family reunion. This acknowledgement of the holiday as such a large media scale opens the possibility that we, as Americans, will widen our gaze and understand Dia de Los Muertos is not about death, or commercializing their images, but it is about the celebration of life. (Lussier, 2017)

Special Thanks to: Marissa Scholler and Spencer’s Gifts

By: Abby Curtis, Anna Saunders, James Maley

Angela Villalba, “History of Day of the Dead ~ Dia de los Muertos”, Reign Trading Co. 1998 – 2018, Dec. 2, 2017, https://www.mexicansugarskull.com/support/dodhistory.html

Incorvia, Samantha. “Day of the Dead Face Painting: Meaning, History, How to Transform Yourself.” Azcentral. October 31, 2016. Accessed April 20, 2018.

Lussier, Germain. “The Long Journey to Make Pixar’s Dia De Los Muertos Movie Coco.” Io9. November 16, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018. https://io9.gizmodo.com/the-long-journey-to-make-pixars-dia-de-los-muertos-movi-1820487496

McDannell, Colleen. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Regina M. Marchi, ”Chapter 3 Day of the Dead in the United States”, Rutgers University Press, 2009, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hj96w.8.

YouTube. November 15, 2017. Accessed April 22, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vCw0_G4_vlo.