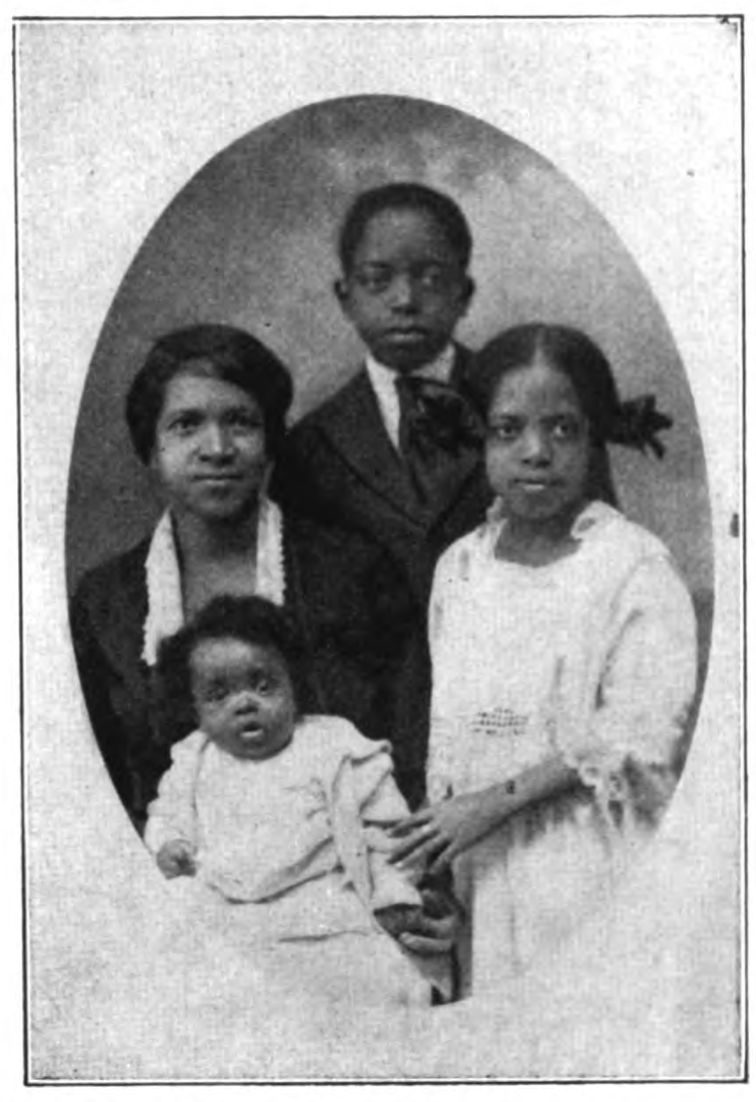

Portrait from History of the American Negro and His Institutions, Volume 5. Circa 1920s.

Image from New York Public Library.

Born in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1877 or 1879, Eugene Dickerson was the son of Wilson Dickerson and Fannie Reeves. In the 1880 Federal Census, his father is listed as a day laborer and his mother as a housekeeper.

An Alumni Journal of the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute from the same year of Dickerson’s graduation. Image from the Library of Virginia, Richmond Virginia.

After attending the local African American public schools in Charlottesville, Dickerson enrolled in the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University) in Petersburg, Virginia, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1896.

Established in 1882, the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute offered a relatively standard nineteenth-century education for Black men and women in Virginia. Coursework on becoming a schoolteacher as well as the ‘classics’ and several branches of mathematics had been provided as early as 1886.

In the long wake of Reconstruction, a great number of African American students had been eager to enter the medical profession as the field, in theory, appeared to offer an opportunity for a relatively stable occupation. In practice, Black physicians still faced much of the discrimination that permeated American society.

As white institutions denied entry to any student of color, Black medical colleges were founded in the late nineteenth century in order to provide educational training for future Black physicians. Entrance requirements were not as rigorous as they are today. After all, these new intuitions had been expressly established for a population that had been systematically, and legally in many cases, denied educational opportunities. Accordingly, knowledge of the English language, elementary mathematics, and a certification of good moral character had generally provided admission well into the 1890s.

Mindful of this, and as a means to adequately meet the needs of its Black students, Leonard Medical School at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina was the first medical school in the United States to adopt a four-year curriculum.

Leonard Hall in 1899. Dickerson would have taken his academic classes in this building. Image from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

Dickerson received his medical degree in 1900 from the Leonard Medical College at Shaw University, and completed his post-graduate work at Howard University where he interned at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., the preeminent institution for Black medicine in the United States.

Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of the Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service.

Image from Oregon State Library, Salem, Oregon.

Rockingham Memorial Hospital, circa 1910s.

Image from Virginia Public Media.

After his time at Howard, Dickerson practiced medicine elsewhere in Virginia, including Gloucester County, before settling in Harrisonburg by 1910. For thirty years, he provided medical care to local Black community members.

Under the reign of Jim Crow, Rockingham Memorial Hospital (now James Madison University’s Student Success Center) had only permitted Dickerson to treat Black patients in a limited capacity in the basement of the hospital. Accordingly, if any of his patients required surgery, they had to travel to Freedman’s Hospital in D.C., where Dickerson did have admitting privileges. That is, if they could afford to spend the additional time and the money to do so.

This had been an almost universal practice by white hospital administrations as Black physicians were overwhelmingly denied hospital admitting privileges through a variety of methods during Jim Crow, including ‘closed-staff’ systems and denial of local American Medical Association (AMA) membership.

Leona, Eugene Jr., Eva Frances, and Austin Curtis. Circa 1920s. Portrait from History of the American Negro and His Institutions, Volume 5. Image from New York Public Library.

In June of 1904, Dickerson married Leona Anderson, daughter of James and Eva Jane Anderson, at the August Street Methodist Church in Staunton, Virginia. Leona, who had graduated from Morgan College in Baltimore (now Morgan State University) and completed post-graduate work at Fisk University in Nashville, had taught for several years in Staunton’s African American public schools before her nuptials. Together, the couple would eventually have four children, Eugene, Jr., James Wilson, Eva Frances, and Austin Curtis.

Tragically, Leona passed away in 1924 after being treated at Freedmen’s Hospital for what was described as a brief illness by her sister, Rheba Ware. Funeral services were held by her family at the John Wesley Methodist Church and she was laid to rest in Harrisonburg’s Newtown Cemetery along with James who had died in infancy.

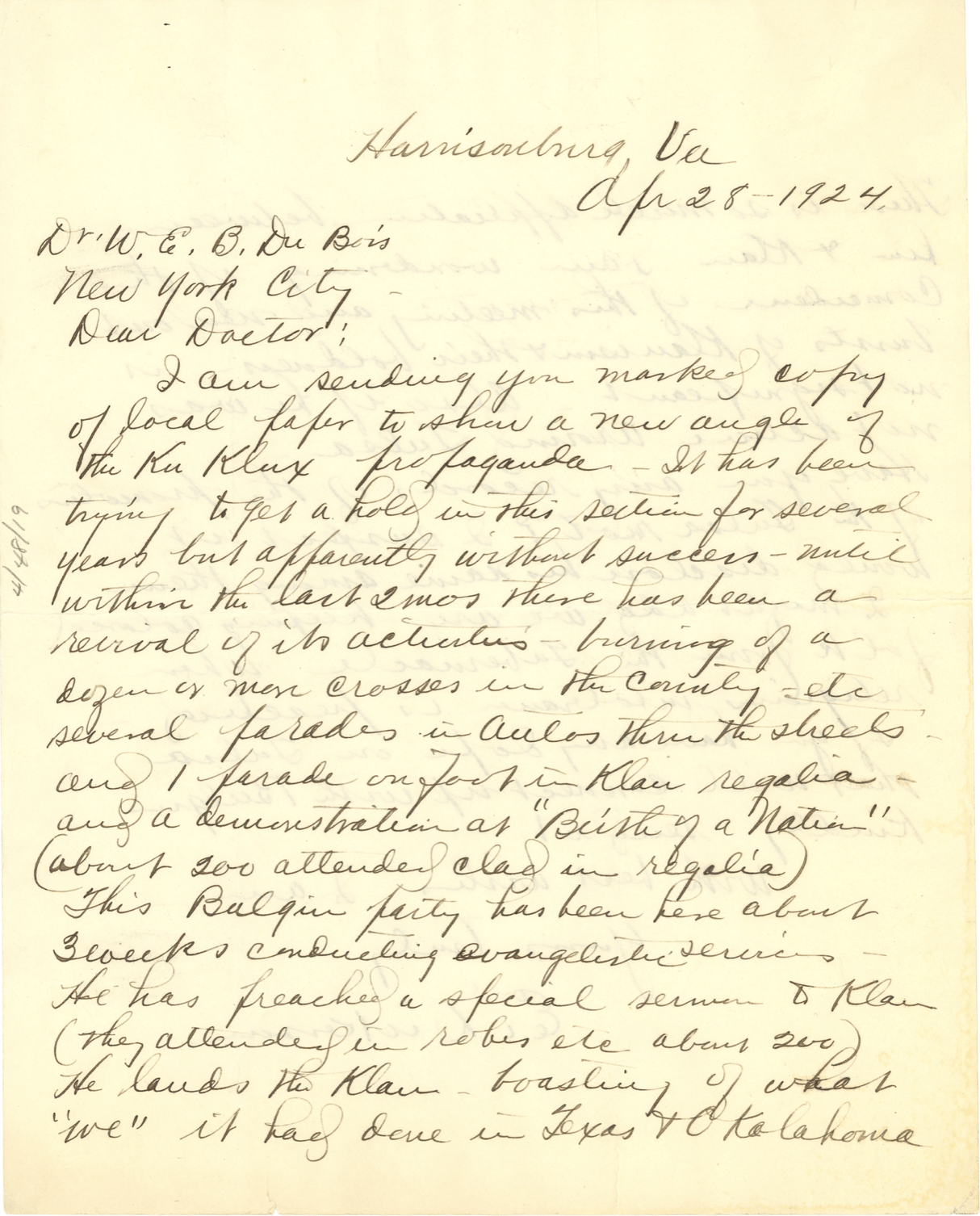

Letter to Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois from Dickerson in April 1924. Image from Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Dr. Dickerson dedicated much of his life to advocating for Black communities.

During the first year of his medical practice in Harrisonburg, Dickerson presented his paper “Conservation of the Health of the Community” at the Colored Teachers’ Institute at the Effinger Street School. Additionally, the doctor had been a member of the Association of Former Internes of Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, a member and delegate to the International Congress on Tuberculosis, a founding member of the local Negro Tuberculosis Auxiliary, a delegate to the 1920 Virginia State Republican Convention, chairman of the local Liberty Loan Committee during the First World War, and a member of the Harrisonburg Community Cooperative Association Board of Directors.

Dickerson also wrote to W.E.B. Du Bois in April 1924, expressing his concerns on the recent rise of Ku Klux Klan activities in Harrisonburg.

After moving back to Washington, D.C. in 1947, Dickerson continued to practice medicine until his death in April 1955. He is buried alongside his wife and son in Newtown Cemetery.

Selected Bibliography

1880 United States Census, Charlottesville, Albemarle County, Virginia.

1910 United States Census, Staunton, Augusta County, Virginia.

1920 United States Census, Harrisonburg, Rockingham County, Virginia.

1930 United States Census, Harrisonburg, Rockingham County, Virginia.

Becker, Trudy Harrington. “Broadening Access to a Classical Education: State Universities in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century.” The Classical Journal 96, no. 3 (2001): 309-22.

Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census. Official Register of the United States, Containing a List of the Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service. Digitized books (77 volumes). Oregon State Library, Salem, Oregon.

District of Columbia, Deaths and Burials Index, 1769-1960.

Hill-Says, Blake, G. K. Butterfield, and C. Eileen Wats Welch. “The First Year: Meeting Professors and Starting Classes.” In Aaron McDuffie Moore: An African American Physician, Educator, and Founder of Durham’s Black Wall Street, 47-52. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

History of the American Negro and His Institutions, Volume 5. Edited by Arthur Bunyan Caldwell. Atlanta, Georgia: A. B Caldwell Publishing Company, 1921.

“Marriage of Dickerson-Anderson.” The Old-Dominion Sun, June 10, 1904.

McAllister, Dale. “Prominent Harrisonburg Physician Dr. Eugene Dickerson.” The Heritage Museum Newsletter 38, no. 1 (Winter 2016): 8-9.

Savitt, Todd L. “The Education of Black Physicians at Shaw University, 1882-1918,” in Black Americans in North Carolina and the South, eds. Jeffrey J. Crow and Flora J. Hatley. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1984.

“Rheba Ware Loses Sister.” The News Leader, December 6, 1924.

Virginia, Births, 1721-2015. Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia.

Virginia, Deaths, 1912–2014. Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia.

Virginia, Marriages, 1785-1940. Virginia Department of Health, Richmond, Virginia.

Ward, Thomas J. Black Physicians in the Jim Crow South. University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

In 2010 Maurine Minor contacted Monticello saying a paper had been found in possession of Dr. George Minor dec’d (her husband’s brother). That paper showed Uriah Levy (who bought Monticello in 1834) had come to the Minor farm in 1835 and bought Aggy (Dickerson). At that sale, Wilson (Dickerson, Dr. Eugene’s father) was bought by John N.C. Stockton of Carrsbrook. Aggy Dickerson died at Monticello in 1858 and her descendants lived on at Monticello for many years. Wilson her brother, when on to have a son, Dr. Eugene Dickerson, one of the early African American medical M.D.s in Va. In 1920 when one of Aggy’s sons died in Charlottesville without a will. One of his potential heirs was Dr. Eugene Dickerson of Harrisonburg Va., a son of his uncle, Wilson. That is how Aggy at Monticello’s surname was figured out. Aggy’s daughter, Martha West, married Willis Shelton, the long time gate keeper at Monticello from the 1870s to 1902.