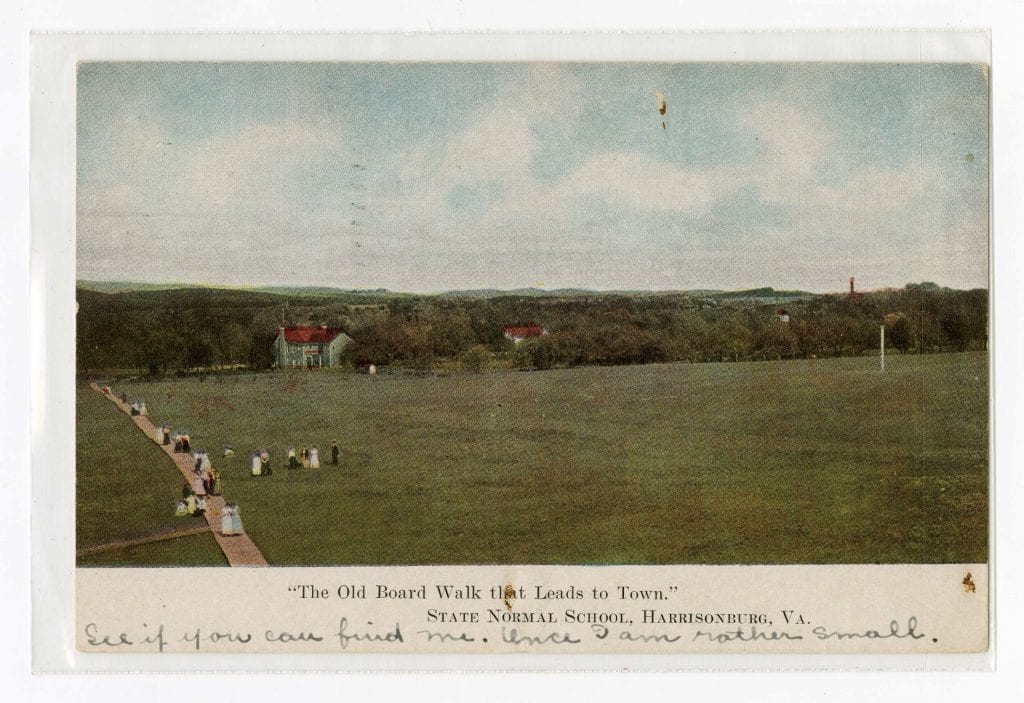

The iconic James Madison University quad looks very much as the designers, first president Julian Burruss and architect Charles Robinson, intended when they designed the campus for the State Normal and Industrial School for Women at Harrisonburg in 1908. An expanse of aesthetically-pleasing lawn surrounded by symmetrically arranged buildings was meant to convey an atmosphere of dignified order, while the enclosed layout would promote the idea that young women enrolled in the Normal School would be protected from the influences of the outside world. The Greco-Roman details of the buildings represented democratic and scholarly ideals, and the blue limestone from which they were built was a testament to the school’s self-sufficiency and resourcefulness, as it was quarried directly from the building site. Once the quad’s limestone was depleted, similar stone was imported for the construction of later buildings to maintain the school’s august congruity. The quad was designed to enable efficient travel between campus buildings, but incessant construction during the institution’s first decade prevented the installation of permanent walkways. Instead, temporary boardwalks made of wood were placed between buildings and leading toward Main Street. The young women attending classes were able to cross the muddy building site without sullying their compulsory white dresses–another symbol of feminine virtue.

Though there was a boardwalk providing access to town, trips had to be approved and supervised. One such outing took place in 1916, when the entire school accepted an invitation to see D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation at the New Virginia Theater in downtown Harrisonburg. The wildly popular film, whose hero leads the South Carolina Klu Klux Klan to reclaim their state from freed blacks, who are shown as feral rapists. The film was protested by the NAACP in several U.S. cities and is still legendary for its derogatory depiction of African Americans and its celebration of white supremacy.

During President Duke’s efforts toward improving and expanding The State Normal School for Women (the name had been changed in 1914), the last of the boardwalks were replaced with concrete paths and the uneven landscape of the quad was levelled into terraces. During the process of grading the slope into flat planes, the “Kissing Rock” was uncovered, but not removed due to cost and concern that there were caverns underneath. Campus legend developed around the boulder, with generations of students believing that a couple who kisses there will later marry. In the 1940’s, students began to challenge the administration, successfully petitioning for changes to the dress code and less restrictive rules about socializing. The school mobilized for the war effort, participating in drives, victory gardens, and air raid drills. In 1946, in response to the GI bill, Madison College regular session included male students for the first time.

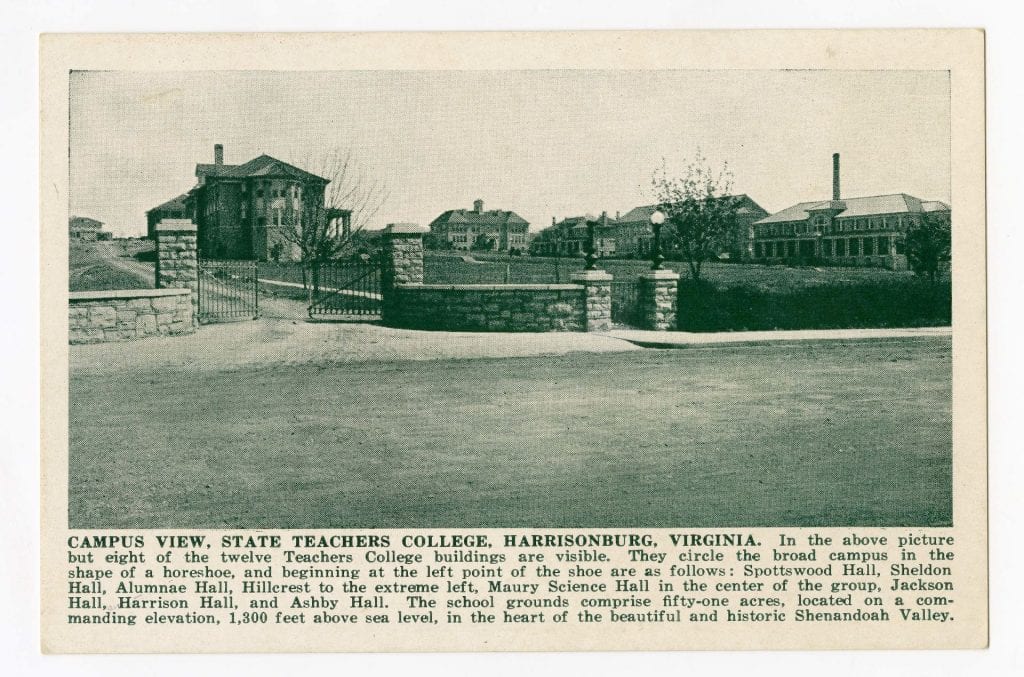

Postcard with an image of the gate and quad of The State Teachers College, 1923. JMU Special Collections.

In 1971, Dr. Carrier started his presidency with grand visions for the school. To boost enrollment, which would fund the rest of his goals, he introduced new majors, emphasized athletics, and encouraged a more relaxed environment on campus. Students no longer had to adhere to dress codes that catered to outdated gender stereotypes and there was a new focus on recreation. Intensive efforts to recruit both male and black students were made, sometimes to the dismay of critics. These new attitudes were evident in the aesthetic of the school as it expanded to meet his vision, with new buildings that no longer conformed to the old distinguished style.

Students on the quad, 1996-1997. JMU Special Collections.

In an interview, Dr. Carrier said, “I don’t think the campus should look alike. I think it looks attractive with the different styles (…) The campus is made up of diversity. Why not have it look different. Why not have the campus reflect the diversity of the students?” Madison College’s innovative president also stressed the importance of an attractive campus in boosting students’ pride. To that end, flowers were planted on the quad and landscaping became a priority. The picturesque lawn became a place for students to socialize and relax, instead of the immaculate symbol of prestige it had once been. The school had a new look, an increasingly diverse student body, and a new attitude, so Dr. Carrier gave it a new name–James Madison University. From 1971-1988, JMU commencement was held on the quad, where Dr. Carrier took the time to shake the hand of each and every graduate.

In 1999, Dr. Rose’s two-hour presidential inauguration took place on the quad, complete with a performance by the Royal Marching Dukes. Students protested the fact that classes had been canceled for the event, when they hadn’t been for Martin Luther King, Jr. day. Again, the protest bore fruit and students were given the holiday off starting in 2001. After the terror attacks of September 11, students gathered on the grassy heart of campus for a moment of silence. The quad had evolved from an abstract symbol of status to an active center of campus life, highlighting all of its most important moments.

Today, the quad still serves all the purposes assigned to it throughout its history. Its carefully manicured lawns represent JMU’s respected reputation, its cobbled paths facilitate easy movement between campus buildings, and its grassy, open spaces offer a place for socializing and relaxing.

By Jessica Corsentino

Sources:

Bluestone, (James Madison University yearbook). Harrisonburg: James Madison University (2000): 88-91.

Bluestone, (James Madison University yearbook). Harrisonburg: James Madison University (2002).

Control # Oversize 102, JMU Historic Photos Online, Special Collections, Carrier Library, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Va.

Crowley, L. Sean. “James Madison University: 1908-1909 to 1958-1959; An Annotated, Historical Timeline.” JMU Centennial Celebration 2007-2008.

Dingledine, Raymond C., Jr. 1959. Madison College : The First Fifty Years, 1908-1958. Harrisonburg, Va., Madison College, 1959.

Lovejoy, Aaron. “The Landscape of Learning: Archaeology of the James Madison University Quad.” Paper written for JMU ANTH 331, (May 5, 2014).

“James Madison University: Buildings Reflect History of University.” Inside Nielson. Spring 2007. http://nielsen.nielsen-inc.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/06/Spring2007.pdf

Ziu, Christina. “We Are the Dogs of JMU [VIDEO].” The Daily Duke. May 2, 2018. https://jmudailyduke.com/2018/05/02/we-are-the-dogs-of-jmu-video/

Recent Comments