Our Project

Working as an interdisciplinary team within a complex, multi-faceted problem space came with many challenges as well as breakthroughs. Scroll through this page to see our reflections on the project processes and outcomes and how we dealt with some of the hurdles we faced.

Our Problem

Our team was initially faced with the challenge of identifying ways in which Financial Technologies, or FinTech, could be used and regulated to benefit low and volatile income Americans. After conducting eight weeks of research into these topics and interviewing a variety of professionals from within the fields of finance and regulation, we narrowed the scope of our problem to focus on the field of small-dollar lending. Therefore, our problem evolved into how to increase both consumer and regulators awareness and understanding of small-dollar lending options available to consumers with a focus on maximizing consumer benefits attained from those services.

The Aspen Institute's Financial Security Program

Our Sponsor

We are in collaboration with the Aspen Institute’s Financial Security Program (FSP). The Aspen Institute is a non-partisan policy studies organization with over 50 programs dedicated to tackling critical issues. The FSP, the program our team is sponsored by, was created as a preeminent initiative to investigate policies or services that could create greater financial security for millions of American households. Their purpose is to capture leading voices within all sectors of the American financial landscape to create palpable, innovative change to improve the financial well-being and security of Americans.

Austin Hinkle

Our Mentor: Senior Policy Advisor at US Treasury Department

Our mentor is Austin Hinkle, a Senior Policy Advisor at the United States Treasury Department. Austin has experience working with financial regulation and provided guidance throughout the project which was instrumental in helping us narrow the scope of our problem and helping us understand the regulatory perspectives.

Our Solution

The final iteration of our minimum viable product (MVP) is a survey-based tool which operates as a matchmaker for consumers looking for small-dollar loans and lenders, whether those lenders be online (website or application) or physical “brick and mortar” lending institution. The tool surveys consumers based on the importance they place on various criteria related to small-dollar loans, such as the value they place on the timeliness of the loan, frequency of which they expect to take out small-dollar loans, and face-to-face interaction. The survey then collects the data on the consumer’s values and preferences and uses those rankings as weights to calculate what types of lending services most and least closely align with the consumer’s needs and preferences.

Our MVP will benefit consumers looking to obtain small-dollar loans by informing them of loan provider options alternative to payday lenders which may better suit their personal needs. It will also give them a stronger understanding of the lending services available on the market as a whole, so they can make the most informed decision about where to take out their loan. Further, because our product is focused on understanding consumer needs and creating recommendations based on those needs, the survey tool could also serve secondarily as a tool to increase awareness of consumer needs and available products that fit those needs among regulators and policy-makers involved in small-dollar lending. This heightened understanding of these needs and options will allow policy and regulation to be shaped by benefits to the consumers that are using these small-dollar lending services in the first place.

Research, Processes, & Major Pivots

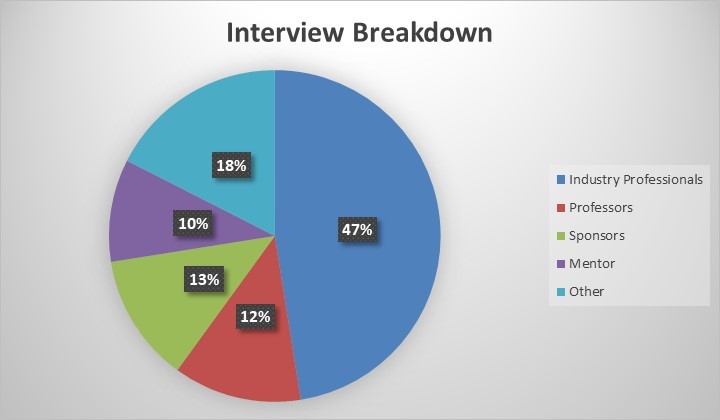

Over the course of eight weeks, our team conducted 40 interviews with 34 different people. We broke our research subjects into five categories: our sponsor, our mentor, professors with a research focus in the fields of finance and regulation, professionals working in the fields of finance and regulation, and other people who do not fit into the aforementioned categories. Within the category of “professionals”, more specifically, we interviewed a California State Regulator who helped us see that there may be a knowledge gap regarding the link between the types of alternative financial services such as FinTechs on the market and how they could benefit low and volatile income consumers specifically.

Aside from interviewing other people with expertise in the industries of finance and regulation, we also conducted extensive outside research to help us better understand various facets of the field and problem we were working on. Early in the process, we conducted cross-national research to determine examples of global “best practices” for where FinTechs were successfully being used and regulated outside the United States. This research was inspired by an interview with one of our sponsors from the FSP who helped us start to understand FinTech regulations abroad and filled us in on what the regulatory landscape looks like in the United States. Based on this, he also helped us see what the US regulatory landscape could look like based on models from other countries. Expanding on this information, each team member was assigned a region based on five continents–North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa–and within each region, we pinpointed specific countries and examined the social, political, and economic factors that affected the diffusion of and regulatory environment surrounding FinTechs within the country. This information helped orient us within the field of FinTech and regulation on a broad scale and allowed us to understand some of the potential assets and barriers for FinTechs within the United States based on these global comparisons.

Another important point of research focused on understanding the low and volatile income consumers that our problem was targeted at helping. Through this, we learned that there are often misconceptions about who these consumers are, with people incorrectly assuming low and volatile income consumers are irresponsible or incompetent in managing their finances. Our research indicated that this is not the case, and in fact, the percentage of Americans that qualify as low or volatile income is much higher than many might initially expect and reaches well into what would be considered the American middle class. For further reading on this topic, check out The Financial Diaries by Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider and The Unbanking of America by Lisa Servon.

A major pivot in our project scope and research came in week four during an interview with our mentor, Austin Hinkle. During this interview, Austin helped us realize that we needed to narrow the scope of our problem, and we initially decided to narrow into investigating credit and ways alternative lending services could help build credit scores. Though this did not remain the final focus of our project, the shift to credit eventually put us on the path of examining the various types of small-dollar lending services and the different benefits and pitfalls they each offer consumers.

Interdisciplinary Teamwork

It has become evident in today’s society that problems are not confined to a single discipline; complex problems are continuously developing that are characterized by a need for strong interdisciplinary efforts towards viable solutions. Although working on the socio-political issues facing the FinTech industry and millions of Americans was initially daunting for a group with little direct experience within the finance and regulatory fields, the interdisciplinary nature of our team allowed us to develop an understanding of the problem from an outside perspective and present valuable insight in this given context. Drawing from seven different fields of study across the university, our team was able to research, develop, and refine potential solutions utilizing the diverse background of each member’s academic interests.

Working as an interdisciplinary team has proven to be extremely valuable for our work; each team member has the ability to provide valuable insight from his or her field of study that helps mold our research and project solutions in a positive direction, and our group has also utilized individual strengths in a flexible, effective way. For example, Aaron’s engineering background proved invaluable when designing our MVPs as he drew on engineering tools such as the Pugh chart and decision matrix, both used to make informed decisions based on weighted criteria. These engineering tools influenced the shape of our final MVP. Aside from different knowledge bases, the seven different fields of study we cover as a team also gave us a variety of types of thinkers. Among the group, we have big-picture thinkers, critical thinkers, global thinkers, and detail-oriented thinkers, which all functioned as different lenses through which we saw and understood facets of our problem, thus contributing to a more nuanced, holistic view of the problem when examined together.