Sophia Rossi, Democracy Fellow (’24 Political Science) and Dr. Kara Dillard, Associate Director, Madison Center for Civic Engagement and Assistant Professor, School of Communication Studies)

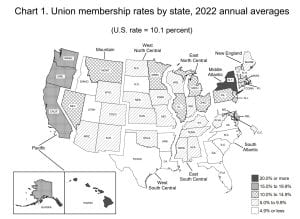

In 1979, labor union membership hit a peak at about 21 million members or about 21% of the workforce. By 2012, that number had declined to 15 million members accounting for only 12% of the workforce. In the private sector, union membership accounts for only 7%. According to 2022 data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 10.1% or one in 10 American workers are part of a labor union. Despite labor union membership nearly being at an all time low, agitation for collective bargaining and collective action to improve work conditions is moving to the forefront of public discourse.

The United Auto Workers strike began on September 15, 2023. That Friday, nearly 13,000 workers walked out on their shifts in three different auto plants in Michigan, Missouri, and Ohio. The UAW strike is a worker-led effort to advocate for better pay, benefits, and treatment by their employers. Some of the demands made by the members of the union include a 46% pay increase over 4 years of work, union representation at new electric battery plants, and a 4-day work week with overtime pay after 32 hours. The strike is targeted at what is known as the “Big 3” automaker companies of General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis.

The United Auto Workers strike began on September 15, 2023. That Friday, nearly 13,000 workers walked out on their shifts in three different auto plants in Michigan, Missouri, and Ohio. The UAW strike is a worker-led effort to advocate for better pay, benefits, and treatment by their employers. Some of the demands made by the members of the union include a 46% pay increase over 4 years of work, union representation at new electric battery plants, and a 4-day work week with overtime pay after 32 hours. The strike is targeted at what is known as the “Big 3” automaker companies of General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis.

While the strike is still ongoing, negotiations have commenced as the consequences of the shortage of workers are beginning to be felt by the Big 3. Just by the end of the second week of the strike General Motors reported they had lost $200 million dollars due to absent employees and work shutdowns. The outcome of this strike and if workers’ demands will be met will either be seen as a calling card to unions across America during this era of economic struggle or a reinforcement of the power dynamic between major companies and their workers as individuals.

Although there have been numerous labor groups and strikes in recent years, the history of labor unions dates all the way back to 1886. On August 20th of that year The National Labor Union was founded in Baltimore, Maryland and paved the way for worker’s rights for centuries to come. This labor group, originally created to protect railroad workers’ rights, is who we can thank for the 8-hour workday. In 1933 the National Industrial Recovery Act created the right for employees to join in a labor union if one is offered in the workplace. Then, in 1935, the Wagner Act created labor union’s rights to collectively bargain and established the National Labor Relations Board (NRLB) to oversee the development and organizing of labor unions in the U.S. The NLRB still provides the main oversight for labor organizing.

Although labor unions have had a fluctuating presence in and out of the American public’s eye, their work is still felt strongly today. There have been a whopping 312 strikes in 2023 alone, down from 424 work stoppages in 2022 involving 224,000 workers . Workers across the country have been turning to collective action to express their frustration with the shared struggles of inflation, unaffordable housing, and increasing disparity between worker and CEO wages. In recent years, groups have been going on strikes across many industries from food service to the health care sector. According to Cornell University’s 2022 labor action tracker, the majority of work stoppages came from those associated with Starbucks or fast food’s Fight for $15 campaign. A notable strike that has taken place recently is the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild strike which put a hold on nearly all production in Hollywood. Most recently, 75,000 healthcare workers, both emergency and non-emergency, walked out of work during the Kaiser Permanente strike. The labor group is looking for higher wages since the issue of short staffing began after the Covid-19 pandemic. With the rise in worker frustration in many sectors across the country combined with a President who coined himself as “the most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in American history,” will more continue to turn to collective action to get their demands met?

Although labor unions have had a fluctuating presence in and out of the American public’s eye, their work is still felt strongly today. There have been a whopping 312 strikes in 2023 alone, down from 424 work stoppages in 2022 involving 224,000 workers . Workers across the country have been turning to collective action to express their frustration with the shared struggles of inflation, unaffordable housing, and increasing disparity between worker and CEO wages. In recent years, groups have been going on strikes across many industries from food service to the health care sector. According to Cornell University’s 2022 labor action tracker, the majority of work stoppages came from those associated with Starbucks or fast food’s Fight for $15 campaign. A notable strike that has taken place recently is the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild strike which put a hold on nearly all production in Hollywood. Most recently, 75,000 healthcare workers, both emergency and non-emergency, walked out of work during the Kaiser Permanente strike. The labor group is looking for higher wages since the issue of short staffing began after the Covid-19 pandemic. With the rise in worker frustration in many sectors across the country combined with a President who coined himself as “the most pro-union president leading the most pro-union administration in American history,” will more continue to turn to collective action to get their demands met?

Laws against creating unions and organizing for collective action continue to create major barriers to union membership. Organizing workplace-by-workplace is a failing strategy, and that entire sectors need to organize, which would require a change in labor law. Many states, including Virginia, are still “right to work” states which prevent the automatic dues collection from those in labor unions. The Taft-Hartley Act, passed in 1947, restricted the development of unions. Globalization and the deindustrialization of the U.S., along with a changing economy from manufacturing to service-based has led many companies to move work overseas where unions are less prevalent.

When this issue was brought up to JMU students, many agreed that striking is a legitimate way for workers to express their frustrations. When asked “Do you believe that labor unions and collective action have the power to make real change?”, the answer was a resounding yes. Many students touched on the point that in our age of social media and constant communication, it is now much easier for groups to spread the word about upcoming strikes or demonstrations to increase participation. Some also expressed that if workers are, understandably, unhappy with pay and treatment during this time of economic struggle even more should take a stand to get their demands met.

The continuous rise in labor groups’ actions and membership attests to the vitality of collective action in our country. The solution for big companies to prevent their own workers from unionizing and organizing strikes is complicated and yet to be found. The dynamic between workers and top executives has always been balanced on respect and fair compensation, but when that balance no longer satisfies both parties there is bound to be a pushback. For workers across America, having the right to unionize and the successes of recent strikes has become a beacon of hope. Through collective action, the individual has the power to be a part of something bigger than themselves and to take a stand for better pay, treatment, and respect.

Recent Comments