By Angelina Clapp (JMU ’20, Political Science), Kyel Towler (JMU ’21, Communication Studies) and Ryan Ritter (JMU ’22, History and International Affairs)

Read the full paper with footnotes here.

Abstract

Modern day prison labor in the United States is rooted in the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and has created a system of slavery that we are more comfortable with. Because of a loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment, Black Americans have historically and presently been subjected to structural disadvantages that reinforce cheap labor from the vestiges of slavery. Incarcerated Americans have been deemed “slaves of the state” which led to the current situation for incarcerated Americans, including the loss of constitutional and voting rights, egregious underpayment for labor, prevention from unionizing, and the list goes on. The development of the prison industrial complex between government and industry, forces many state organizations and public institutions, and universities in Virginia, including JMU, utilize the “services” of prison-made goods.

Background: Tracing Modern Day Slavery to the 13th Amendment

On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, the text of which stated that:

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Although many celebrated the abolition of slavery, the 13th Amendment created an exception to allow slavery to continue by other means. The 13th Amendment has been used to force incarcerated people in the United States to participate in labor and other arduous tasks against their will. Through the rise of laws targeting Black Americans and en masse conviction, Black Americans have been disproportionately incarcerated and oppressed by the incarceral system. While many agree now that the enslavement and bondage of human beings is immoral, unethical and against American democratic values, many are unaware of the forms slavery takes in today’s society and the institutions and practices that are its direct descendants.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, laws were created that were specifically meant to target Black people. Actions like “mischief” and “insulting gestures” were criminalized and widely enforced throughout the country, and especially in the South. The resulting increase in incarcerated Black people proliferated the market for convict leasing, a system in which southern states contracted their prison populations to outside industries at a price. Thus, incarcerated people were soon being systematically exploited for their labor. This practice became the law in 1871 when the Virginia Supreme Court in Ruffin v. Commonwealth declared that incarcerated people were legally indistinguishable from enslaved people, or, to quote the court, “slaves of the state.” The ruling legitimized the notion that incarceration is merely another form of slavery, but one that the general public is much more comfortable with or is unaware of altogether.

Additionally, Southern states also began creating large prisons during this time in order to house the growing population of incarcerated people. The demand for prisons continued to rise as the number of people charged with crimes increased in the South. Many of these prisons were built on old plantation land, and some even continued the tradition by being named after the plantation that they were built on. One such example is the Louisiana State Penitentiary which is commonly referred to as “Angola” after the former plantation on the land it is situated.

As the era of convict leasing slowed, the Jim Crow era ushered in new policies and laws that disproportionately impacted Black Americans. The Jim Crow era can be defined as “a set of laws, policies, attitudes, and social structures that enforced racial segregation across the Southern United States from the Civil War to the mid-to-late 20th century.” Though many discriminatory laws and practices introduced during Jim Crow have now been repealed, the practice of mass incarceration has since replaced them. Michelle Alexander, scholar and author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, describes this as a process where “people are swept into the criminal justice system, branded criminals and felons, locked up for longer periods of time than most other countries in the world who incarcerate people…and then released into a permanent second-class status in which they are stripped of basic civil and human rights, like the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to public benefits.” This system has been put in place in order to control every aspect of the lives of incarcerated people. It also reaches far outside of American prisons and penitentiaries and into our cultural norms and political institutions. In many states, people with felony convictions lose their right to vote following the end of their sentence.

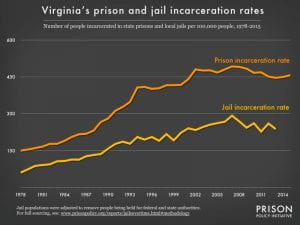

The New Era of mass incarceration in America began in 1973 and continues to this day.This new era can be attributed to three causes of disparities in state imprisonment. The first of that being a new era of policymaking in the criminal justice system. These new policies expanded the use of imprisonment as punishment for all felony charges, eventually becoming widely used for sex and drug offenses. Additionally, more policies were adopted with the goal of increasing the likelihood and longevity of imprisonment. The implementation and strict enforcement of harsh drug laws is viewed as one of the main reasons for the large racial disparities that are seen in prisons today. According to scholars, black people are four times as likely as white people to be arrested for drug offenses and 2.5 times as likely to be arrested for drug possessions despite the fact that white people and black people use drugs at the same rate. The creation of policies like “Stop-and-frisk” allowed for police officers to stop and question anyone who they deemed suspicious. Because racial disparities begin at the initial encounter people of color have with police their race is more likely to impact the outcome of the interaction. Evidence shows that initial police stops are unlikely to result in incarceration, however the prevalence of prior convictions increases chances of future incarceration, something that disproportionately impacts people of color. Implicit bias impacts the perceptions the public can have on people of color. Multiple pieces of evidence point to the fact that beliefs about the dangerousness and threats to public safety are related to these perceptions.Scholars have found that people of color receive harsher punishments than their white counterparts because they are perceived as being more violent and imposing a greater threat to public safety.

The New Era of mass incarceration in America began in 1973 and continues to this day.This new era can be attributed to three causes of disparities in state imprisonment. The first of that being a new era of policymaking in the criminal justice system. These new policies expanded the use of imprisonment as punishment for all felony charges, eventually becoming widely used for sex and drug offenses. Additionally, more policies were adopted with the goal of increasing the likelihood and longevity of imprisonment. The implementation and strict enforcement of harsh drug laws is viewed as one of the main reasons for the large racial disparities that are seen in prisons today. According to scholars, black people are four times as likely as white people to be arrested for drug offenses and 2.5 times as likely to be arrested for drug possessions despite the fact that white people and black people use drugs at the same rate. The creation of policies like “Stop-and-frisk” allowed for police officers to stop and question anyone who they deemed suspicious. Because racial disparities begin at the initial encounter people of color have with police their race is more likely to impact the outcome of the interaction. Evidence shows that initial police stops are unlikely to result in incarceration, however the prevalence of prior convictions increases chances of future incarceration, something that disproportionately impacts people of color. Implicit bias impacts the perceptions the public can have on people of color. Multiple pieces of evidence point to the fact that beliefs about the dangerousness and threats to public safety are related to these perceptions.Scholars have found that people of color receive harsher punishments than their white counterparts because they are perceived as being more violent and imposing a greater threat to public safety.

The media’s reporting and perceptions of crimes has a large impact on the public opinion of crime. It has a tendency to focus on the most serious crimes, mainly those committed by people of color. This therefore causes the news to be flooded with images of people of color portrayed as criminals which impacts the public’s perception of all people of color.

The third disparity is structural disadvantages that disproportionately impact people of color. These disadvantages impact people of color long before they have any interaction with the criminal justice system. Disparities that occur during imprisonment are the result of social factors including things related to poverty, employment, housing and family issues that may impact what happens to them during their very first encounter with law enforcement. Scholars have found that African Americans make up the majority of people living in poverty where a large amount of socio-economic vulnerabilities can cause higher crime rates, thus exposing them to disparities in the criminal justice system that may negatively impact them. People of color in America are disadvantaged from the very beginning.

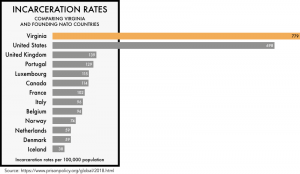

America makes up 5 percent of the world’s population; however, we house 25 percent of the world’s inmate population as a whole causing us to have the largest incarceration rate in the world. Out of the total 6.8 million incarcerated population, 2.3 million are black. According to a report by Dr. Ashley Nellis, African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at more than five times the rate of whites, and at least ten times the rate in five states. Because of this, mass incarceration has become a method of disenfranchising Black voters, shrinking the electorate, and engineering voter suppression. Additionally, Black Americans are incarcerated for drug-related offenses at a rate 10 times higher than that of white Americans although drug usage among the races is roughly the same. The high rate of incarceration among black people has major impacts on their mental and physical health and overall quality of life. Even though the 13th amendment protects against “cruel and unusual punishment” in America, prisons are overcrowded, have harsh conditions, exploit the labor of the incarcerated people, and lack the proper capacity to respond to national emergencies like pandemics.

America makes up 5 percent of the world’s population; however, we house 25 percent of the world’s inmate population as a whole causing us to have the largest incarceration rate in the world. Out of the total 6.8 million incarcerated population, 2.3 million are black. According to a report by Dr. Ashley Nellis, African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at more than five times the rate of whites, and at least ten times the rate in five states. Because of this, mass incarceration has become a method of disenfranchising Black voters, shrinking the electorate, and engineering voter suppression. Additionally, Black Americans are incarcerated for drug-related offenses at a rate 10 times higher than that of white Americans although drug usage among the races is roughly the same. The high rate of incarceration among black people has major impacts on their mental and physical health and overall quality of life. Even though the 13th amendment protects against “cruel and unusual punishment” in America, prisons are overcrowded, have harsh conditions, exploit the labor of the incarcerated people, and lack the proper capacity to respond to national emergencies like pandemics.

Prison Industrial Complex

The Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) refers to the “overlapping of interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.” The private prison industry has expanded over the years to the point where the increase of incarcerated people in America incentivizes companies because of the appeal of profits. A growing number of popular companies have found that exploiting incarcerated people for their labor is easier, and cheaper than producing those products by other labor means. This aspect of the PIC is, again, encouraged by the loophole found in the 13th Amendment. Prisons, companies, and governments continue to profit from the prison labor industry. Incarcerated individuals work in prison for an average of $0.33 per hour. And because of cheap prison labor, governments are less likely to try to address the issue of mass incarceration. Furthermore, in 1977, the Supreme Court ruled in Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners Labor Union that incarcerated people do not have the right to join labor unions under the First Amendment. Thus, incarcerated people do not have any of the same rights or protections awarded to other working Americans.

Laws in Virginia + Prison population

The Virginia code requires that all “departments, institutions, and agencies of the Commonwealth that are supported in whole or in part with funds from the state treasury for their use” must purchase items manufactured by incarcerated persons in state correctional facilities.According to the Prison Policy Initiative, Virginia pays incarcerated people between $0.55 and $0.80 an hour for their labor. The Virginia Correctional Enterprises (VCE) is the main entity that runs the prison labor business in Virginia. Incarcerated people join programs in prison to manufacture goods. The VCE then sells those goods for a substantial profit while paying their workers mere cents per hour. Because of this, Virginia is actively participating in and contributing to the prison-industrial complex. VCE also works closely with the Prison Industry Enhancement program (PIE). PIE works to connect private businesses to the manufacturing process in order to further exploit incarcerated people’s labor. The private businesses that work with PIE are exempted from unemployment taxes. A loophole in Section 26 of the United States Code 3306(c)(21) states that they do not have to pay taxes because the manufacturing within prisons by incarcerated people is not considered employment. This system thrives off of punishment. If the exaggerated punishment of people stopped, the system would cease to exist and the stakeholders would stop making money. Therefore, these stakeholders have little incentives to fight for prison reform.

The Virginia code requires that all “departments, institutions, and agencies of the Commonwealth that are supported in whole or in part with funds from the state treasury for their use” must purchase items manufactured by incarcerated persons in state correctional facilities.According to the Prison Policy Initiative, Virginia pays incarcerated people between $0.55 and $0.80 an hour for their labor. The Virginia Correctional Enterprises (VCE) is the main entity that runs the prison labor business in Virginia. Incarcerated people join programs in prison to manufacture goods. The VCE then sells those goods for a substantial profit while paying their workers mere cents per hour. Because of this, Virginia is actively participating in and contributing to the prison-industrial complex. VCE also works closely with the Prison Industry Enhancement program (PIE). PIE works to connect private businesses to the manufacturing process in order to further exploit incarcerated people’s labor. The private businesses that work with PIE are exempted from unemployment taxes. A loophole in Section 26 of the United States Code 3306(c)(21) states that they do not have to pay taxes because the manufacturing within prisons by incarcerated people is not considered employment. This system thrives off of punishment. If the exaggerated punishment of people stopped, the system would cease to exist and the stakeholders would stop making money. Therefore, these stakeholders have little incentives to fight for prison reform.

In January 2019, Virginia lawmakers failed to pass a bill introduced by Delegate Lee Carter (D-Manassas) that would have changed the prison-work program, run by Virginia Correctional Enterprises, so that the goods are sold on the open market instead of directly to state facilities and universities. In January of 2020, Virginia lawmakers voted to push their criminal justice reform agenda back to 2021 citing the need to “study some of the issues.” In the COVID-19 era, prison populations have to make up the gaps in production of personal protection equipment (PPE) and other medical items needed in the fight against the virus. Incarcerated people have to make the masks that will be worn by themselves and the Department of Corrections staff in order to prevent the spread of the virus within prisons. This is another example of the exploitation of incarcerated people. Correctional facilities have been heavily criticized for not doing enough to protect their population from the virus all while their prisoners are forced to produce protective equipment for the general public.

JMU and Prison Labor

As laid out in section § 53.1-47 of the Code of Virginia, public universities in the state are required to purchase items that were made by incarcerated people in prisons. Due to this, a large amount of furniture at JMU was created by incarcerated people in state prisons. According to JMU’s website, JMU is mandated to use VCE for all furniture purchases unless VCE grants a release for the purchase or the furniture is purchased through the TSRC Quick Ship Program. VCE may provide an exemption/release if there is no comparable item to what is requested”. This loophole of not using furniture produced by prison labor is treated as a secondary option, essentially nudging the university to use VCE for it’s furniture purchases. In January of 2019, according to Ned Oliver of the Virginia Mercury, Virginia lawmakers dismissed a bill patroned by Delegate Lee Carter, D-Manassas, which challenged VCE and its malpractices behind the manufacturing of furniture, office supplies, etc. Within the subcommittee meeting, Delegate Emily Brewer, R-Simthfield, said “she had toured those inmate-staffed factories and said the workers, incarcerated as they may be, work voluntarily, learn skills and take pride in their labor.” Whereas Carter contrasted “Inmates have a choice to sit in confinement or work for as little as 80 cents an hour,” he told the committee”. There have been more efforts to change these laws in Virginia but none have passed in the General Assembly. One bill was created that would view incarcerated people as employees who would make minimum wage for their work. However this bill failed in March of this year. JMU and many other Virginia universities and colleges have yet to publicly detail their stance on the matter.

Discussion Questions

- Why are we as a society more comfortable with slavery in its current form?

- What responsibility does the JMU community have to recognize that their items are manufactured by incarcerated people?

- How can students use their voices for prison reform?

- What sustainable steps can you take to advance criminal justice reform?

- What are the real reasons some states don’t allow incarcerated people and felons to vote?

- What are the implications of not allowing this population of people to vote?

- Why does the United States have the largest number of incarcerated people?

Recent Comments