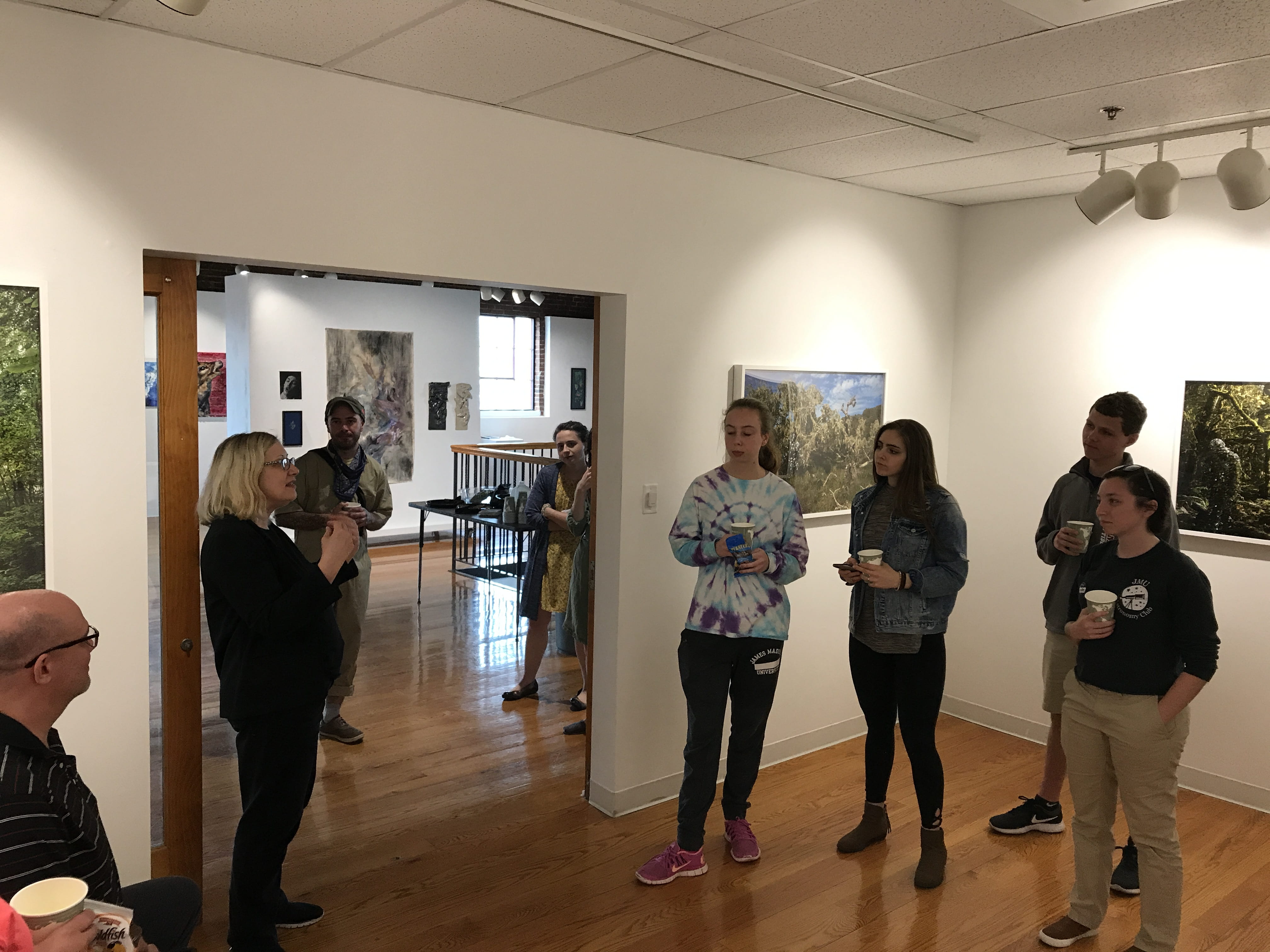

Professor, Artist and Activist Pato Herbert spent time deliberating his works that are part of the exhibit “In If Not Always Of” with JMU students on April 11 at JMU’s New Image Gallery. Herbert was a Visiting Scholar hosted by JMU’s School of Art Design and Art History during Spring 2019. He will return in Spring 2020 as a Cultural Connections Artist in Residence through CVPA.

Post by Madison Farabaugh, Honors Civic Engagement

Pato Herbert is a man of many callings. From working with the homeless, LGTBQ+ grassroots efforts, communities of color, and HIV advocacy/awareness campaigns, he uses his creativity and social skills as a “visual artist, educator, and cultural worker” in order to bring about positive social change. Herbert values deliberation about the purpose of his work because it mirrors the interconnectedness and interdependence of the human condition. After years of immersing himself in diverse communities, Herbert incorporates his experiences and insight into artwork by calling out current events of our social, political, and environmental spheres and exposing areas where civic engagement is desperately needed.

JMU Professor of Art Corinne Diop arranged for Pato Herbert’s exhibit at the New Image Gallery.

On Thursday April 11, JMU students and Harrisonburg residents had the opportunity to meet with Herbert at the New Image Gallery as he facilitated an open dialogue surrounding his featured art exhibition entitled “In If Not Always Of.” With this series, he uses a creature he calls the oscillator who appears in various nature landscapes to convey civic concerns. Deliberating with Herbert and his works prompted us to think: what does it mean to be in but not always of civic life?

Herbert referenced the dilemma of the exhibit’s title as a connection to our society. “In If Not Always Of” prompts us to question what it means to be in a community, but not always of it. We discussed how voting, political campaigns, and other democratic processes are sites where citizens are affected by outcomes but do not always participate in them. As such, the mirror-like oscillator and many citizens alike reflect on their surroundings but refrain from interfering.

On the other hand, the title also draws attention to the controversies that occur between nature and culture. What is to be extracted and what is to be protected? Who is displaced in the creation of such spaces? Is there hypocrisy in defining nature by limiting it to places, like state or national parks, where it can stand “untouched” by human impact?

Herbert acknowledges how art can be alienating for some because they feel there has to be a right answer in the way it is interpreted. However, his own point of view holds that, in the ambiguity of feelings of perspectives, there need not be only one way of looking at a work of art. What is important is sharing your viewpoints with others and discussing the different meanings you each can see. He compares this type of discussion to the way governments and publics should interact: collaboratively. One should not force ideas or action onto the other; they should have mutual opportunity to “hash out interpretations” without merely trying to get a vote of approval. It is this comparison that exemplifies Herbert’s own leadership: considering the validity of opinions that were not yours originally.

Recent Comments