On April 13 and 14, the Northeast Neighborhood Association, the James Madison Center for Civic Engagement and Community Service Learning, in partnership with Women of Color, the Harrisonburg Citizen and the Honors College organized an experiential learning tour to Montpelier and local sites to develop a better understanding of the connections between the struggles for freedom, rights and equality, and the contributions of social justice movements to American society and democracy.

On April 13 and 14, the Northeast Neighborhood Association, the James Madison Center for Civic Engagement and Community Service Learning, in partnership with Women of Color, the Harrisonburg Citizen and the Honors College organized an experiential learning tour to Montpelier and local sites to develop a better understanding of the connections between the struggles for freedom, rights and equality, and the contributions of social justice movements to American society and democracy.

Download the Arc of Citizenship primer for the tour.

Learning Objectives

- Develop a better understanding and appreciation for Black intellectual and cultural contributions to American society and democracy.

- Develop a better understanding of the history and legacy of slavery, and the struggle for freedom and rights.

- Through authentic experience and discussion, develop a better understanding of the connections between the history of slavery and the struggle for freedom and rights and contemporary political and socioeconomic inequities.

- Encourage critical thinking and constructive deliberation regarding currently social justice issues.

- To encourage dialogue and action on difficult public problems.

- To develop greater multicultural competence and awareness of issues that affect different communities.

- To develop a better understanding of local issues and make connections with the Harrisonburg and Rockingham communities.

Mere Distinction of Colour

Mere Distinction of Colour

“We have seen the Mere Distinction of Colour made in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.” -James Madison, 1787

Mere Distinction of Colour exhibit offers the opportunity to hear the stories of those enslaved at Montpelier told by their living descendants, and explore how the legacy of slavery impacts today’s conversations about race, identity, and human rights. Visitors will also see Montpelier’s connection to the national story of slavery – and discover the economic, ideological, and political factors that cemented the institution in the newly-created American nation and Constitution.

Gilmore Cabin

The Gilmore Cabin provides a glimpse at what life was like for African Americans after emancipation.

The Gilmore Cabin provides a glimpse at what life was like for African Americans after emancipation.

George Gilmore was born a slave at Montpelier in 1810. Following his emancipation after the Civil War, he purchased land across the street from what are now the gates of Montpelier, and built his family’s cabin in 1873.

Gilmore was listed as a farmer on the 1880 census, meaning that he had some control over his own crop production. Multiple beads, buttons, and other type of sewing materials were found under the cabin, indicating that Polly Gilmore contributed to the family by her work as a seamstress. The property was bought by William duPont after George Gilmore’s death. However part of the land is still owned by the Gilmore family.

Train Depot at Montpelier: The Architecture of Segregation

The 1910 Train Depot provides a glimpse into the African American struggle for Civil Rights.

The 1910 Train Depot provides a glimpse into the African American struggle for Civil Rights.

Constructed in the Jim Crow era, the signs “Colored” and “White” still hand above the waiting room doors at the Train Depot in the Montpelier Train Station. The majority of the building has been restored to serve as a reminder of what segregation looked and felt like at Montpelier. William duPont, owner of Montpelier in 1910, built the depot to accommodate cargo and visitors to the estate as well as his own personal travels.

Dallard-Newman House and Northeast Neighborhood

Credit: Northeast Neighborhood Association pamphlet provided by Steven Thomas.

Constructed c. 1895 at 192 Kelley Street, the historic Dallard-Newman House is one of the city’s oldest and most enduring monuments to African American culture and heritage. The building, constructed by freed slaves, Ambrose and Reuben Dallard in 1885, is a fascinating record of urban life in this community. Its history begins with efforts at economic recovery in the post-Civil War era (1865-1877), the founding of the first educational institutions for persons of color, the development of the thriving community of Newtown around the house, and the near hundred and fifty years that followed up, up until today.

The Dallard/Newman house is one of the few middle-class African American homes to survive in Harrisonburg, since most of the African-American neighborhoods were targeted for demolition during the Urban Renewal movement of the 1960’s. Its endurance, coupled with the prominence of the Newman family and the vital role it played in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Harrisonburg, makes it a unique and important structure, one worthy of preservation in the Northeast Community.

The house previously believed to be Thomas Harrison’s

An historic downtown Harrisonburg structure was thought for generations to be the home of the town’s founder, Thomas Harrison. The City of Harrisonburg bought the property with matching funds from the Margaret Grattan Weaver Foundation with plans to restore it. Weaver, a prominent local philanthropist who died in 2001, served as president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in her lifetime. The Southern Poverty Law Center counts United Daughters of the Confederacy among the leading proponents of the “cult of the lost cause.”

An historic downtown Harrisonburg structure was thought for generations to be the home of the town’s founder, Thomas Harrison. The City of Harrisonburg bought the property with matching funds from the Margaret Grattan Weaver Foundation with plans to restore it. Weaver, a prominent local philanthropist who died in 2001, served as president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in her lifetime. The Southern Poverty Law Center counts United Daughters of the Confederacy among the leading proponents of the “cult of the lost cause.”

During research prior to beginning restoration efforts, Dr. Carole Nash, Associate Professor of GS, ISAT at JMU, along with other researchers found that the construction of the building fell between the spring of 1789 and 1790. Their findings meant that the house could not have been built by Thomas Harrison because he died in 1785. Dr. Nash and her team also uncovered artifacts in the basement of the home that suggested enslaved people lived in the basement, and that the building might have served as an inn.

According to Steven Thomas of the Northeast Neighborhood Association, the research findings are “an invaluable opportunity and tool for truth-telling and racial reconciliation should city officials demonstrate the bold leadership this moment calls for…The enslaved inhabitants of the cellar at the building formerly known as the ‘Thomas-Harrison House’ would have sought refuge in historic Newtown in the years following the Civil War. Exploring a broader collaboration between all parties involved in the downtown restoration effort and those conducting similar work in northeast Harrisonburg is the starting point for a city government and community devoted to transforming the historical harms of white supremacy.”

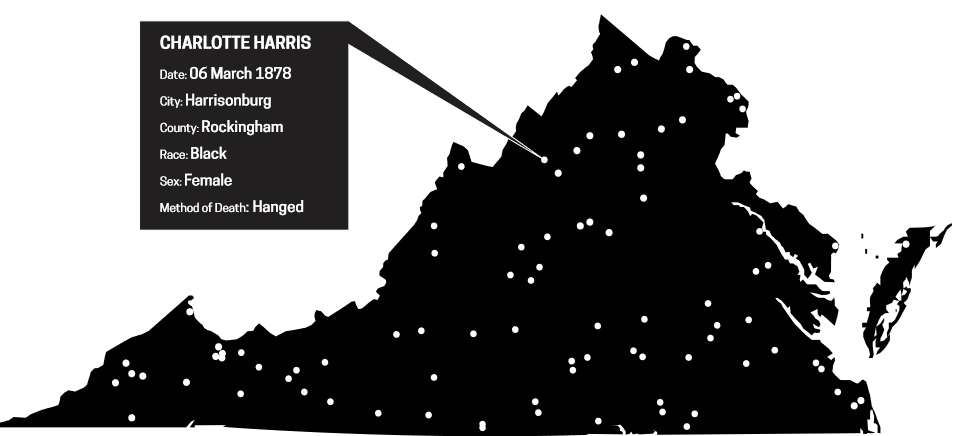

Lynching, Mass Racial Terror and Community Remembrance: Charlotte Harris

Credit: Racial Terror and Lynching in Virginia, a research project led by Gianluca De Fazio, assistant professor in the Department of Justice Studies at JMU.

About a dozen persons with blackened faces hanged Charlotte Harris, a black woman, on March 6th, 1878 near Harrisonburg, in Rockingham County, Virginia. Harris was accused of instigating the burning of a barn.

On Thursday, February 28th, 1878, the barn of Henry Sipe in Rockingham County burned down, and a young black boy, Jim Ergenbright (or Arbegast), was arrested with the accusation of having set the barn on fire (Evening Star). Charlotte Harris was later accused of being the instigator of the burning of the barn, and, on March 6th, she was arrested and taken into the custody of the Rockingham County Jail in Harrisonburg (Alexandria Gazette). At about 11 PM, two men appeared in front of the building with cocked revolvers, demanding Harris from her jail cell. According to The Daily Dispatch, the two armed men “informed the guard that if they surrendered her peaceably it would be well for them; if not, they must take the consequences. But at this moment a rush of armed men (in appearance black) made an entrance and seized Charlotte”. The disguised party took Charlotte Harris about 400 yards from the jail and hanged her to a tree.

On March 16th, 1878, the Governor of Virginia offered a $100 reward for the capture of the lynchers of Charlotte Harris; about ten days later, a grand jury in Rockingham County was unable to identify any parties responsible for the lynching (Alexandria Gazette). Jim Ergenbright, the young boy accused of having burned Mr. Sipe’s barn, was acquitted from all charges on April 16th, 1878 (Alexandria Gazette).

Federal Courthouse: Downtown Harrisonburg

Completed in 1940, the federal courthouse building in downtown Harrisonburg was added to the National Register of Historic Places in September 2019. Among the major aspects of its historical significance are some cases heard at the courthouse more than 60 years ago, after the Supreme Court’s famous 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling that public school segregation was unconstitutional. Implementing that decision, however, was left up to local school boards. In Virginia, many resisted. Read more by Andrew Jenner at WMRA here.

Completed in 1940, the federal courthouse building in downtown Harrisonburg was added to the National Register of Historic Places in September 2019. Among the major aspects of its historical significance are some cases heard at the courthouse more than 60 years ago, after the Supreme Court’s famous 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling that public school segregation was unconstitutional. Implementing that decision, however, was left up to local school boards. In Virginia, many resisted. Read more by Andrew Jenner at WMRA here.

JMU Campus History by Dr. Meg Mulrooney

1966 yearbook photo of Ms. Sheary A. Darcus, the first black student admitted to Madison College.

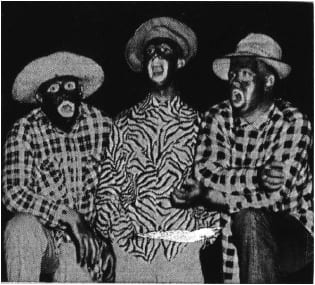

[Excerpts from Dr. Mulrooney’s blog] Just as it was in American culture, broadly, blackface on this campus functioned as a form of cultural violence against Black people. Along with other behaviors, it supported the cultural construction of white, Southern womanhood even if “not all students” participated. That these young women were training to become teachers must also be recognized, for many familiar children’s songs, like Oh Susanna and Cindy, Cindy were minstrel songs.

1954 yearbook photo showing a scene from the “Senior Plantation Party.”

Although it did start to diminish after WWII, blackface activities persisted here, as they did on other all-white Virginia campuses, through the era of the state’s massive resistance to federal desegregation mandates in the 1950s-1960s and into the decades of resistance to affirmative action in the 1970s-1990s. It is not surprising, then, to see in yearbooks and student newspapers evidence that some individuals who attended JMU in the 1980s “blacked up” at private parties, in homecoming parades, or at Greek events. Like earlier forms of blackface in the the Jim Crow era, these performances cannot be separated from the broader context of organized white resistance to higher education integration. Madison College admitted its first black student, Sheary Darcus Johnson, in 1966, and its first black graduate student in 1969, however, desegregation proceeded very slowly throughout the 1970s. In fact, Virginia’s official policy of resistance did not end until the administration of Gov. John Dalton began in 1978, the same year that the Supreme Court’s famous Bakke decision gave rise to the concept of “reverse discrimination.” What was it like to be a Black student or staff member or instructor at Madison at that time? In previous public history seminars, my students and I explored the transformation of this institution in a series of web-based exhibits called Madison in the 1970s. That project demonstrates that the changing trajectory of American higher education, including contemporary efforts to make JMU more diverse and inclusive, are very recent indeed.

Confederate Heritage at JMU: Research by Dr. Meg Mulrooney

[Excerpted from Dr. Mulrooney’s blog.] Built in 1909, Maury Hall opened just in time to welcome the first class of students enrolled at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women. At that time, the building was called Science Hall and it was the sole academic structure: it held the president’s office, the library, the bookstore, and all of the classrooms. Many of the students came here to become teachers and partake of an innovative curriculum designed to meet a shared standard or ‘norm’. The only other buildings of note at the Normal were a dormitory, which housed a student dining room in the basement and a modest second-floor apartment for the president and his family, and a former farmhouse that accommodated the female faculty.

[Excerpted from Dr. Mulrooney’s blog.] Built in 1909, Maury Hall opened just in time to welcome the first class of students enrolled at the State Normal and Industrial School for Women. At that time, the building was called Science Hall and it was the sole academic structure: it held the president’s office, the library, the bookstore, and all of the classrooms. Many of the students came here to become teachers and partake of an innovative curriculum designed to meet a shared standard or ‘norm’. The only other buildings of note at the Normal were a dormitory, which housed a student dining room in the basement and a modest second-floor apartment for the president and his family, and a former farmhouse that accommodated the female faculty.

“Bluestone Hill” as it appeared ca. 1915. From left to right: Science Hall (Maury), Dormitory 1 (Jackson) and Dormitory 2 (Ashby). JMU Special Collections.

In 1917 the trustees of the Normal approved a recommendation from a faculty member to rename its academic buildings for Confederate heroes. Science Hall was renamed in honor of Matthew Fontaine Maury, a Virginia-born scientist (the “Father of Oceanography” or “Pathfinder of the Seas”) and commander in the Confederate Navy. His biographer John Grady notes that Maury was a controversial figure while alive, but by this date, thanks especially to his daughter’s 1888 memoir, he had become widely romanticized as a “great benefactor if his race.” Similarly, the original dormitory became Jackson Hall in recognition of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, the Confederate general who led the 1862 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and a second dormitory became Ashby Hall in honor of a local Confederate cavalry officer, Turner Ashby, of nearby Port Republic. Together, these structures memorialized not only the specific deeds of these three men, but a particular interpretation of the Civil War—an interpretation that the faculty and administration expected the future teachers to pass on to Virginia schoolchildren.

Discussion Questions

What stood out to you about this experience?

What was new, reinforcing, surprising or challenging?

What can you do after this experience?

What can JMU do to address these histories and legacies, and to create a more just and inclusive democracy?

Recent Comments