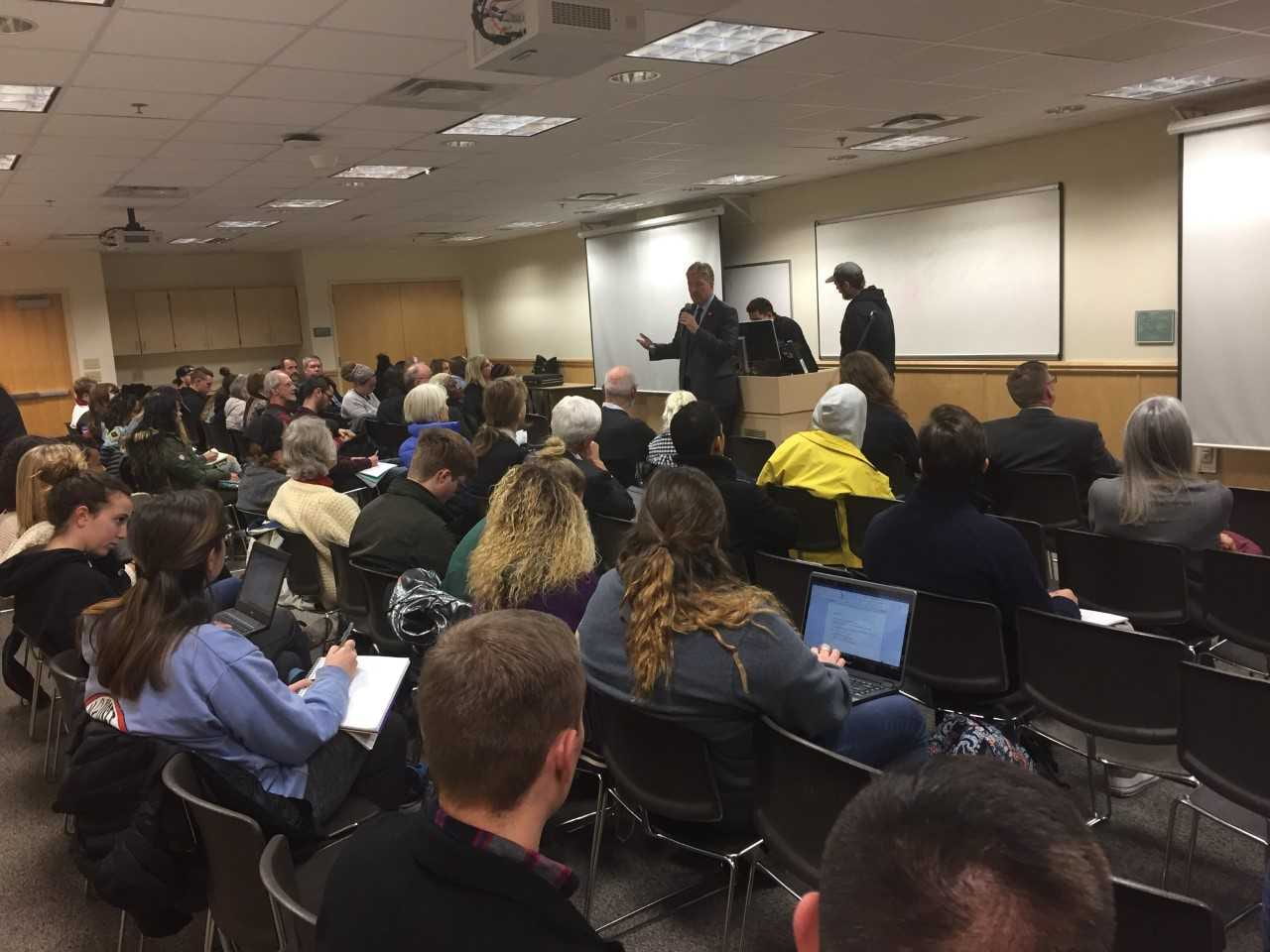

On December 4, the Mahatma Gandhi Center for Nonviolence at James Madison University hosted a discussion on parole and parole reform in Virginia with Virginia Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security Brian J. Moran and Adrianne Bennett, Chair of the Virginia Parole Board.

On December 4, the Mahatma Gandhi Center for Nonviolence at James Madison University hosted a discussion on parole and parole reform in Virginia with Virginia Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security Brian J. Moran and Adrianne Bennett, Chair of the Virginia Parole Board.

In 1994 the Virginia General Assembly abolished parole and required that felony offenders serve at least 85 percent of their sentences, with the potential to earn good-behavior credits toward an early release date. At the time, the General Assembly and then-Governor George Allen (R) believed that abolishing parole would prevent new felony and reduce recidivism.

During the event Secretary Moran explained that abolishing parole in Virginia also stemmed from the War on Drugs and other national efforts around criminal justice under the Clinton administration, such increasing the number of police officers on the streets.

There is generally bipartisan agreement among politicians that abolishing parole strengthened the integrity of Virginia’s justice system. As evidence, both sides of partisan aisle point to the statistic that Virginia has the lowest recidivism rate in the country, at just 22.4%.

But Virginia also spends about $1.05 billion each year on its corrections system. A recent state report also highlighted that Virginia spent more than $201 million on health care for those incarcerated in fiscal 2017 alone. This equates to about 17% of the total Department of Corrections annual budget to provide health care to about 30,000 inmates at 41 state facilities, and comes to about $6,500 per inmate. But high costs are just one reason reformers argue that it’s time to revisit the state’s parole policy.

Another issue raised during the discussion at JMU is that as a result of abolishing parole, there have been inconsistencies and wide discrepancies in sentencing, especially for low-risk offenders. In particular, sentencing prior to the Fishback v. Commonwealth case (and subsequent “Truth in Sentencing” laws), juries in Virginia were not aware of the state’s abolition of parole and doled out heavy-handed sentences between 1995-2000 without knowledge of the law.

One recommendation is to reduce the number of nonviolent offenders. The Department of Corrections reports that 9,000 offenders, representing 24 percent of the state’s prison population, have no violent crimes on their records. This amounts to spending about $243 million annually, or $27,000 per inmate to house nonviolent offenders (and it costs more for older prisoners). At the JMU event, Secretary Moran argued that there is bipartisan support for investing in reentry instead.

In addition to Secretary Moran and Adrianne, several community members and several previously incarcerated individuals spoke at the event. One community member argued that state funds would be better used to improve the educational system. She argued that with no opportunity for parole, the Department of Corrections turns into the “department of housing”. Audience members also voiced concerns over keeping people who improved behavior and people who are aging in correctional facilities.

One Justice Studies student who attended the event reflected, “Justice is defined as giving a person what he or she deserves. So, if a prisoner has turned their life around and deserves to be rewarded, why is parole not an option for young prisoners anymore? They are still people and still have their whole life in front of them, why must it be done in a prison?” Another Justice Studies student noted, “I had no idea Virginia had abolished parole in 1995; I also had no idea that it was such a controversial issue. This event really opened my eyes to a part of the American justice system that I didn’t know existed.”

If you missed the event and want to learn more, check out the Valley Justice Coalition, which regularly organizes meeting and community discussions, or take a Justice Studies course with Professor Terry Beitzel!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks