The New Yorker by the Numbers

by Daniel Worden

In its first issue, published with a cover date of February 21, 1925, The New Yorker declares itself to be a serious magazine, with a distinctive humorous tone and a commitment to facts:

The New Yorker starts with a declaration of serious purpose but with a concomitant declaration that it will not be too serious in executing it. It hopes to reflect metropolitan life, to keep up with events and affairs of the day, to be gay, humorous, satirical but to be more than a jester.[1]

The magazine’s distinctive blend of metropolitan humor is perhaps best embodied in its beloved gag cartoons. And a distinctively literary approach to reporting is also sketched out in that opening editorial note:

[The New Yorker] will publish facts that it will have to go behind the scenes to get, but it will not deal in scandal for the sake of scandal nor sensation for the sake of sensation.[2]

The New Yorker’s opening qualifications about its purpose—it is a serious magazine, but not too serious; it will publish stories about current events, but not stoop to the level of a sensationalistic tabloid—exhibit a cultural positioning that literary critic Tom Perrin has identified as distinctive of “middlebrow modernism.”[3] The magazine claims a commitment to the formal project of modernist aesthetics, yet its contributors often exhibit a disdain for the opacity and experimentalism that accompanies modernism’s aesthetic project, favoring instead more traditionally representational art forms that focus on everyday life.

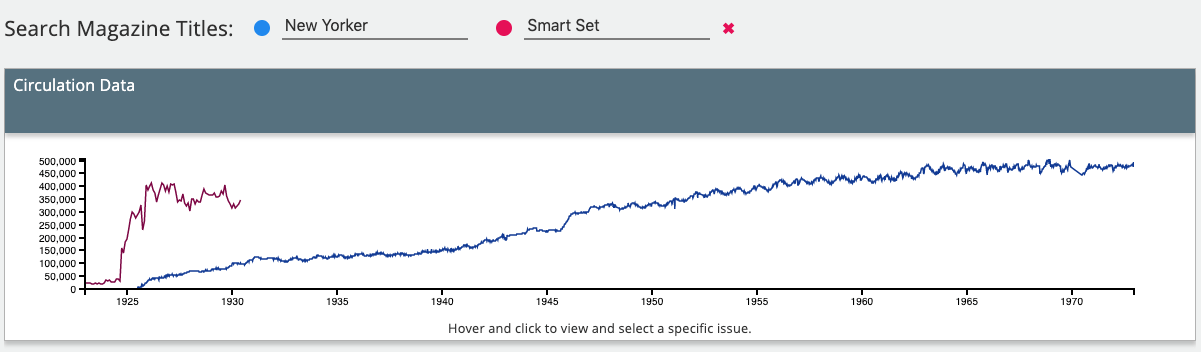

Looking at the circulation numbers made available through Circulating American Magazines, it is clear that The New Yorker existed alongside other “smart” magazines of the early twentieth century.[4] The magazine has similar circulation numbers as, for example, American Mercury, College Humor, and Scribner’s, and it is far surpassed by the much larger circulation numbers of magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Esquire, and The Saturday Evening Post. The namesake of “smart” magazines, the Smart Set’s circulation peaks at around 400,000 between 1925 and 1929. In that same period, The New Yorker’s circulation grows from 5,694 on July 4, 1925 (the first reported numbers available) to 90,000 by the end of 1929. The New Yorker would level out at a circulation of between 400,000 and 500,000 by the mid-1950s. What this data makes visible is not only The New Yorker’s steady rise in circulation compared to its peer “smart” magazines of the period, but its relative stability in the mid-century moment.

In 1965, the writer Tom Wolfe published a two-part satirical profile of the New Yorker in the New York magazine (the Sunday magazine of the New York Herald Tribune at the time). The occasion of Wolfe’s article was the fortieth anniversary of The New Yorker, which had transitioned from its founding editor, Harold Ross, to its second editor, William Shawn—Shawn became editor following Ross’s death in 1951. In his profile, Wolfe finds Shawn to be a meek follower of Ross’s original vision, “the mummifier, the preserve-in-amber, the smiling embalmer . . . for Harold Ross’s New Yorker magazine.”[5] Wolfe then criticizes The New Yorker’s literary output: “The New Yorker comes out once a week, it has overwhelming cultural prestige, it pays top prices to writers, and for forty years it has maintained a strikingly low level of literary achievement [. . .] The short stories in The New Yorker have been the laughingstock of the New York literary community for years.”[6]

While Wolfe finds The New Yorker’s fiction to be especially monotone and uninspiring, it is worth noting that during this same period of circulation stability, The New Yorker was publishing landmark works of literary nonfiction, including John Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946), Lillian Ross’s Picture (1952), James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time” (1962), Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), and Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1965). Ironically, the very nonfiction form that Wolfe would advocate for—a style of literary reportage that he would call the “New Journalism”—was being honed in the very magazine he felt necessary to set himself against.

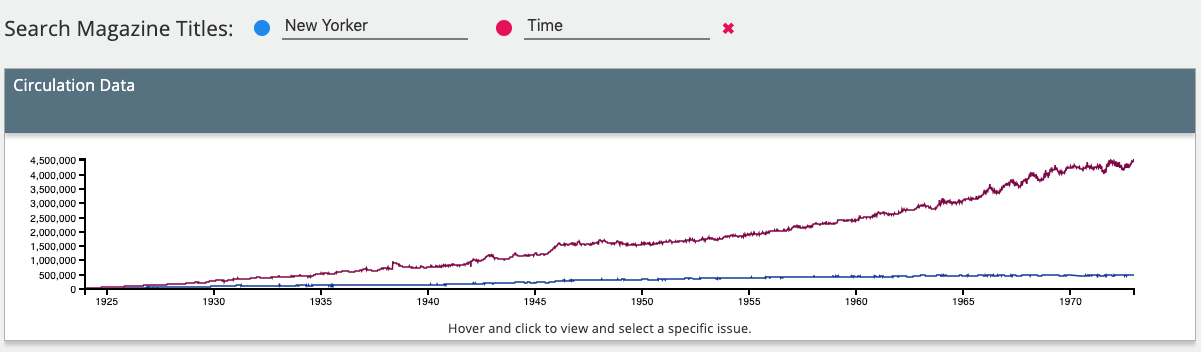

On the one hand, Wolfe is correct in 1965 to critique The New Yorker for being mummified—it was no longer rising in circulation, and it had achieved a stable readership. Yet on the other hand, the circulation numbers demonstrate that the New Yorker was a niche magazine, especially compared to the circulation of Time Magazine. Time reaches 4,000,000 in 1968, while The New Yorker remains between 400,000 and 500,000 with a largely coastal circulation. The New Yorker looms large in how literary culture thinks of itself, especially when it is located in New York City, and that stature may depend, in part, on the power of the magazine’s cultural prestige rather than its circulation.

Daniel Worden is the author of Neoliberal Nonfictions: The Documentary Aesthetic from Joan Didion to Jay-Z, a book that details how documentary art across media grappled with privatization, entrepreneurial individualism, and other neoliberal forces from the 1960s to the present. He is Associate Professor in the School of Individualized Study and the Department of English at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

[1] “Of All Things,” The New Yorker (21 Feb. 1925), 2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See Tom Perrin, “On Blustering: Dwight Macdonald, Modernism, and The New Yorker,” Writing for the New Yorker: Critical Essays on an American Periodical, ed. Fiona Green (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015), 228-248.

[4] For an account of “smart” magazines, see Catherine Keyser, Playing Smart: New York Women Writers and Modern Magazine Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2010).

[5] Tom Wolfe, “Tiny Mummies!: The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!,” Hooking Up (New York: Picador, 2000), 262.

[6] Tom Wolfe, “Lost in the Whichy Thickets: The New Yorker,” Hooking Up (New York: Picador, 2000), 278-279